Kamagra gibt es auch als Kautabletten, die sich schneller auflösen als normale Pillen. Manche Patienten empfinden das als angenehmer. Wer sich informieren will, findet Hinweise unter kamagra kautabletten.

Ews-fli1-mediated suppression of the ras-antagonist sprouty 1 (spry1) confers aggressiveness to ewing sarcoma

Oncogene (2016), 1–11 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/16

ORIGINAL ARTICLEEWS-FLI1-mediated suppression of the RAS-antagonistSprouty 1 (SPRY1) confers aggressiveness to Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz1, TGP Grünewald2,3, D Surdez2, L García-García1, J Carlos Lázaro1, T Kirchner3, L González-González1, A Sastre4,P García-Miguel4, SE López-Pérez1, S Monzón1,5, O Delattre2 and J Alonso1

Ewing sarcoma is characterized by chromosomal translocations fusing the EWS gene with various members of the ETS familyof transcription factors, most commonly FLI1. EWS-FLI1 is an aberrant transcription factor driving Ewing sarcoma tumorigenesisby either transcriptionally inducing or repressing specific target genes. Herein, we showed that Sprouty 1 (SPRY1), which is aphysiological negative feedback inhibitor downstream of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors (FGFRs) and other RAS-activatingreceptors, is an EWS-FLI1 repressed gene. EWS-FLI1 knockdown specifically increased the expression of SPRY1, while other Sproutyfamily members remained unaffected. Analysis of SPRY1 expression in a panel of Ewing sarcoma cells showed that SPRY1 wasnot expressed in Ewing sarcoma cell lines, suggesting that it could act as a tumor suppressor gene in these cells. In agreement,induction of SPRY1 in three different Ewing sarcoma cell lines functionally impaired proliferation, clonogenic growth and migration.

In addition, SPRY1 expression inhibited extracellular signal-related kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalinginduced by serum and basic FGF (bFGF). Moreover, treatment of Ewing sarcoma cells with the potent FGFR inhibitor PD-173074reduced bFGF-induced proliferation, colony formation and in vivo tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner, thus mimickingSPRY1 activity in Ewing sarcoma cells. Although the expression of SPRY1 was low when compared with other tumors, SPRY1was variably expressed in primary Ewing sarcoma tumors and higher expression levels were significantly associated with improvedoutcome in a large patient cohort. Taken together, our data indicate that EWS-FLI1-mediated repression of SPRY1 leads tounrestrained bFGF-induced cell proliferation, suggesting that targeting the FGFR/MAPK pathway can constitute a promisingtherapeutic approach for this devastating disease.

Oncogene advance online publication, 4 July 2016;

Here we report on the tumor suppressive role of another

Ewing sarcomas are aggressive bone and soft-tissue sarcomas

repressed EWS-FLI1-targeted gene, namely Sprouty 1 (SPRY1),

mostly affecting children and young adults.Although the 5-year

which is a negative feedback inhibitor of the RAS/mitogen-

survival in patients with localized disease increased significantly

activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-related kinase

on the addition of systemic chemotherapy to protocol treatments

(RAS/MAPK/ERK) pathway downstream of the fibroblast growth

in the 70–80 the prognosis and survival of patients with

factor receptor (FGFR).

metastatic or recurrent disease remained generally very poor.

SPRY1 is part of the mammalian Sprouty gene family consisting

Indeed, Ewing sarcoma features high rates of early metastasis with

of four members (SPRY1–4), which share important sequence

20% of patients having detectable metastasis at diagnosis.

similaritiessuch as a highly conserved cysteine-rich domain

The molecular hallmarks of Ewing sarcoma are nonrandom

in the C-terminal region (which is also found in the SPRED family

chromosomal translocations generating in-frame fusion of the

of proteins) and a short amino acid sequence in the N-terminus.

EWS gene on chromosome 22 and the C-terminus of a member

SPRY proteins differ largely in their tissue distribution, activity

of the ETS family of transcription factors (that is, FLI1, ERG, ETV1, FEV,

and interaction partners,thus suggesting non-redundant

ETV4 and POU5F1) including the DNA-binding domain(reviewed in

functions. SPRY1 is an upstream antagonist of RAS that is

Mackintosh et This fusion gives rise to aberrant EWS-ETS

activated by ERK, providing a negative feedback loop for RAS

transcription factors, EWS-FLI1 being present in 85% of cases.

signaling. Of note, about one-third of all human cancers are

EWS-FLI1 induces massive deregulation of protein expression

thought to carry a mutated RAS gene that activates downstream

by either transcriptionally inducing or repressing specific target

It has been suggested that SPRY1 may have a tumor

genes, many of which are involved in the oncogenic process.

suppressor function in specific tumors, as its expression is

For instance, EWS-FLI1 induces the expression of NR0B1 (DAX1),

decreased in several human cancers such as breast and prostate

EGR2, NKX2.2, CCK, PRKCB or STEAP1,while suppressing IGFBP3,

LOX, DKK1 or TGFBIIR.All these genes have been shown to

overexpression in tumor cell lines inhibits cell proliferation,

be important in Ewing sarcoma pathogenesis.

migration and anchorage-independent growth in vitro

1Unidad de Tumores Sólidos Infantiles, Instituto de Investigación de Enfermedades Raras, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Majadahonda, Spain; 2INSERM U830 ‘Genetics and Biologyof Cancers' Institut Curie Research Center, Paris, France; 3Laboratory for Pediatric Sarcoma Biology, Institute of Pathology, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany; 4Unidad hemato-oncología pediátrica, Hospital Infantil Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain and 5Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER U758), Instituto deSalud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. Correspondence: Dr J Alonso, Unidad de Tumores Sólidos Infantiles, Instituto de Investigación de Enfermedades Raras, Instituto de Salud Carlos III,Ctra. Majadahonda-Pozuelo km 2, Majadahonda Madrid 28220, Spain.

E-mail: Received 5 January 2016; revised 5 May 2016; accepted 30 May 2016

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz et al

In this study, we show that SPRY1 acts as a tumor suppressor in

A673/TR/shEF grown in the absence of doxycycline. However,

Ewing sarcoma cells, and that SPRY1 repression is necessary for cell

a strong induction of SPRY1 protein was observed on doxycycline-

proliferation and migration. Interestingly, SPRY1 repression was

mediated EWS-FLI1 knockdown.

important to ERK pathway activation. Moreover, FGFR inhibition

We next studied whether the inhibition of SPRY1 expression

mimicked SPRY1 effect on proliferation and growth, indicating that

could be a common feature of Ewing sarcoma cells. We first

SPRY1 has an important role in Ewing sarcoma. Finally, elevated

analyzed the levels of SPRY1 mRNA and protein in a panel of eight

SPRY1 expression correlated with improved overall survival of

Ewing sarcoma cell lines harboring different EWS-FLI1 or EWS-ERG

Ewing sarcoma patients and inversely correlated with metastasis

fusion proteins (Supplementary Table 1). As shown in

at diagnosis. Collectively, our data indicate that EWS-FLI1-mediated

SPRY1 mRNA and protein were undetectable in all Ewing

repression of SPRY1 confers a growth advantage to Ewing sarcoma

sarcoma cell lines analyzed. Interestingly, the mRNA levels of

cells, and that SPRY1 levels constitute a novel biomarker for outcome

the other members of the SPRY family were variably expressed in

prediction of Ewing sarcoma patients. Taken together, these results

this panel of Ewing sarcoma cells. These data could also be

suggest a rationale for targeting FGFR/SPRY1/RAS/MAPK/ERK

confirmed assessing larger public data sets. For instance, analysis

pathway as a new therapeutic approach in this devastating disease.

of Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia data setshowed that Ewing sarcoma cell linesexhibited the lowest SPRY1 levels among all tumor cell lines

analyzed (Supplementary Figure 1).

SPRY1 expression is strongly inhibited by EWS-FLI1 in Ewingsarcoma cell lines

SPRY1 induction impairs cell proliferation of Ewing sarcoma cells

Analysis of a gene expression profile of A673 Ewing sarcoma cell

The strong downregulation of SPRY1 by EWS-FLI1, its absence of

line genetically modified to express a specific small hairpin RNA

expression in Ewing sarcoma cell lines and the finding that it acts

directed against EWS-FLI1 mRNA on doxycycline stimulation (A673/

as a negative feedback inhibitor of the RAS/MAPK/ERK cascade

TR/shEF) (Gene Expression Omnibus accession code: GSE36007)

suggest a potential function of SPRY1 inhibition in Ewing sarcoma.

indicated that SPRY1 is strongly downregulated by EWS-FLI1. These

To test this hypothesis, we generated three doxycycline-inducible

microarray results were confirmed by reverse transcription–quanti-

SPRY1 Ewing sarcoma cell lines (A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1

tative PCR experiments. As depicted in EWS-FLI1

and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1) and subjected them to several functional

knockdown led to a dramatic re-expression of SPRY1 mRNA (up to

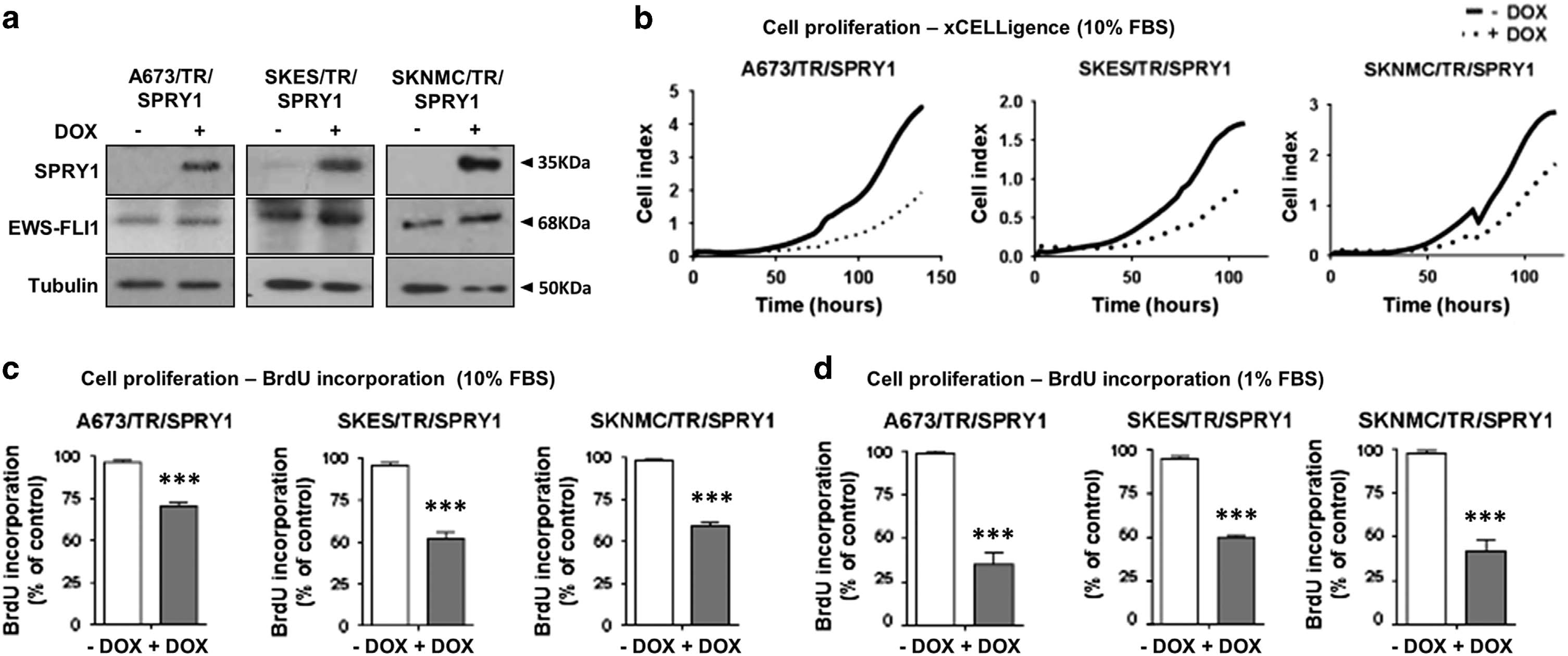

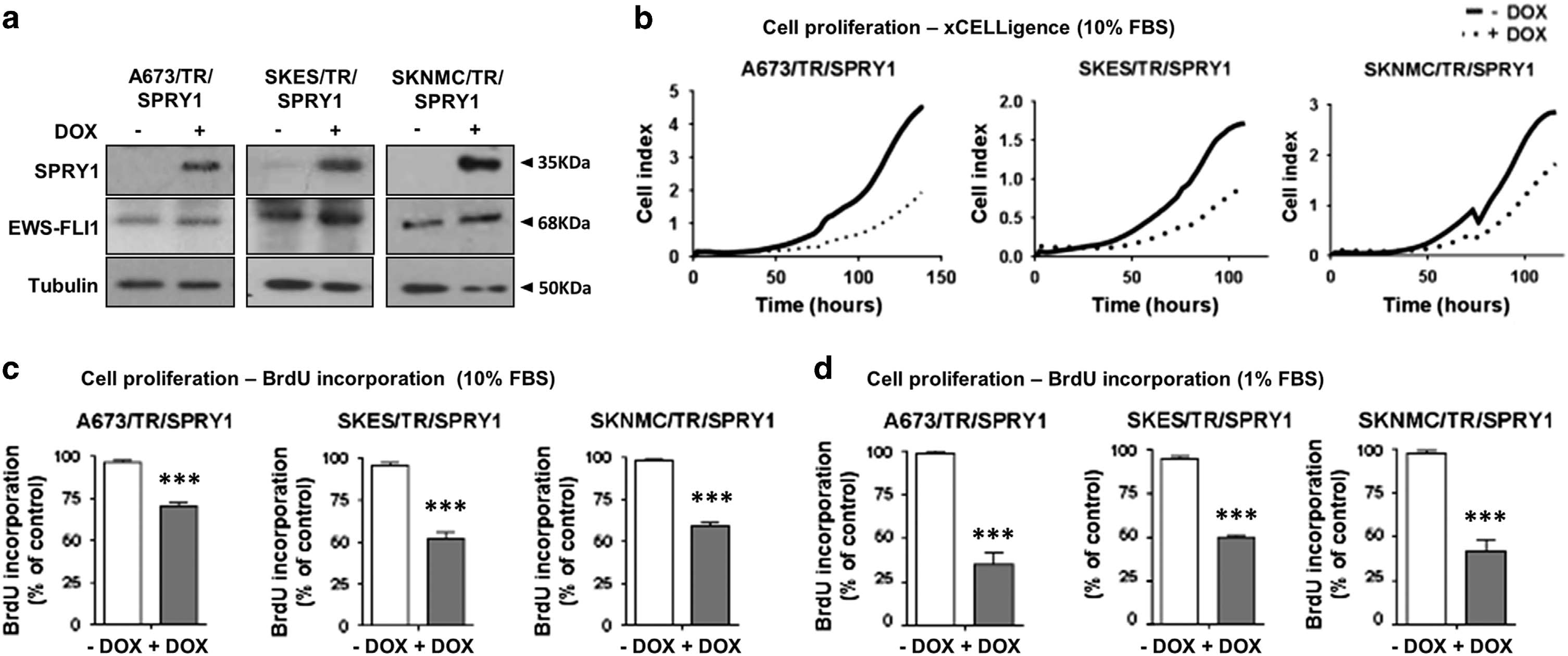

assays. As shown in these genetically modified Ewing

1000-fold compared with controls), whereas the mRNA levels

cell lines express high levels of SPRY1 protein on doxycycline

of the other members of the SPRY family (SPRY2, 3 and 4) were

stimulation, whereas the levels of the EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein

only minimally affected. Analysis of SPRY1 protein levels in the

remain unaffected. Thus, they constitute a suitable model to test

A673/TR/shEF cell model confirmed these results. As shown in

the consequences of exclusive SPRY1 re-expression in Ewing

, SPRY1 protein was undetectable by western blotting in

sarcoma without affecting the levels of EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein.

Figure 1. SPRY1 is negatively regulated by EWS-FLI1 oncoprotein. (a) Time course of SPRY1, 2, 3 and 4 on EWS-FLI1 doxycycline-inducible

knockdown in A673/TR/shEF. EWS-FLI1 expression and two known target genes such as LOX and NR0B1 were included as controls. mRNAlevels were quantified by real-time reverse transcription–quantitative PCR (RT–qPCR), normalized to that of TBP (reference gene) and referred

to unstimulated cells. Figure shows data of one out of three independent experiments done in triplicate with equivalent results. EWS-FLI1inhibition in A673/TR/shEF cells selectively upregulates SPRY1 more than 1000 times over the rest of the members of the SPRY family of genes.

As expected, LOX appears upregulatedand NR0B1 downregulatedon EWS-FLI1 knockdown. (b) SPRY1 protein is re-expressed on EWS-FLI1knockdown in A673/TR/shEF cells. SPRY1 protein is undetectable by western blotting in A673 cells grown in the absence of doxycyclineand thus expressing EWS-FLI1. Incubation of A673/TR/shEWSFLI1 cells with doxycycline (1 μg/ml, 72 h) inhibits EWS-FLI1 expression and

dramatically induces re-expression of SPRY1 protein. Tubulin was used as a control for loading and transferring. (c) SPRY1 is undetectable

at protein level by western blotting in eight Ewing sarcoma cell lines. Expression of the different EWS-ETS proteins is also shown. Tubulin wasused as a control for loading and transferring. (d) SPRY1, 2, 3 and 4 mRNA levels in Ewing sarcoma cell lines. Box plot shows the absence

of SPRY1 expression in all Ewing sarcoma cell lines tested relative to other members of the SPRY family. The figure shows the expression levelsnormalized to that of TBP (reference gene).

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcomaF Cidre-Aranaz et al

Figure 2. SPRY1 re-expression impairs proliferation in Ewing sarcoma cell lines. (a) A673/TR, SKES/TR and SKNMC/TR Ewing cell lines

expressing constitutively the tetracycline repressor (TR) were infected with a doxycycline-inducible lentiviral vector encoding theSPRY1 cDNA. The figure shows the expression of SPRY1 protein in whole protein extracts isolated from A673/TR/SPRY1 (clone 1), SKES/TR/

SPRY1 (clone 7) and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 (clone 2) cells stimulated with doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml, 72 h). High SPRY1 levels were detected in

all three cell lines after doxycycline stimulation. EWS-FLI1 expression was not affected by SPRY1 ectopic expression. The same blotwas stripped and incubated with anti-tubulin as a control for loading and transferring. (b) Cell proliferation was assayed in A673/TR/SPRY1,

SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells using an xCELLigence assay with or without re-expression of SPRY1 (DOX, 1 μg/ml). Graphs depict

the growth curves of the cells cultured in the absence or presence of doxycycline during 120 h and they show one representative experimentout of three independent experiments performed. Re-expression of SPRY1 produces a significant inhibition of cell proliferation. Slight artifacts

in the graphs at 72 h are a consequence of media change and subsequent readjustment of the conditions in the xCELLigence device and donot affect the final result. (c) A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were plated in octuplicates and cultured in thepresence or absence of doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml) for 72 h in 10% tetracycline-free FBS-supplemented media (standard culture conditions).

Cell proliferation was assayed by bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation into DNA. Graphs depict the percentage of cell proliferationof doxycycline-treated cells (expressing SPRY1) versus control. Figure depicts one representative experiment (mean ± s.d.) out of three

independent experiments performed (***P o0.005). (d) Cells were plated and cultured as described in c, but kept in 1% FBS-supplemented

media (low-serum conditions). Cell proliferation is significantly inhibited in doxycycline-treated cells (expressing SPRY1) versus control. Figure

depicts one representative experiment (mean ± s.d.) out of three independent experiments performed (***Po0.005).

First, we studied the effect of SPRY1 induction on cell proliferation

Finally, the three Ewing cell lines harboring the SPRY1 construct

. Induction of SPRY1 in these Ewing sarcoma cell lines

were cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline and

on doxycycline stimulation significantly reduced their proliferation.

assayed for cell cycle in non-synchronized cells by flow cytometry.

This was observed using real-time monitoring of cell number

As shown in Supplementary Figure S3, the impairment in cell

(xCELLigence instrument, ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA)

proliferation in SPRY1-re-expressing cells seems partially due to a

and by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation assays

cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase, although these results were not

). Notably, no effect on cell proliferation was

observed in cells carrying the empty vector, both in the absence and

Taken together, these results provide evidence that SPRY1

in the presence of doxycycline (data not shown). Cell proliferation

induction impairs cell proliferation as well as clonogenic and

inhibition was observed in standard culture media supplemented

anchorage-independent growth of Ewing sarcoma cell lines.

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) ) and in low-serum (1% FBS) conditions as well Induction of SPRY1 in

SPRY1 induction impairs migration of Ewing sarcoma cells

cells grown in low-serum conditions exhibited an even stronger

We next analyzed the effect of SPRY1 induction in Ewing sarcoma

reduction of cell proliferation (probably suggesting that in

cells on cell migration. As shown in SPRY1 induction

conditions where there is a diminished availability of growth factors,

reduced the ability of A673, SKES and SKNMC Ewing sarcoma

such as in the tumor microenvironment, SPRY1 is able to markedly

cells to close an artificial wound produced in a confluent

impair cell proliferation.

cell monolayer (in vitro wound-healing assay). In addition, SPRY1

Similarly, induction of SPRY1 expression reduced clonogenic

re-expression significantly impaired migration of Ewing sarcoma

growth of the three Ewing sarcoma cell lines plated at very low

cells through a porous membrane (transwell assay) No

density in medium supplemented with 5% FBS, whereas cells

differences in the migratory properties were observed in cells

carrying the empty vector remained unaffected on doxycycline

carrying the empty vector (data not shown).

treatment and Supplementary Figure 2A). When cellswere tested for anchorage-independent growth in soft agar,

SPRY1 repression is necessary for ERK activation and proliferation

no significant differences were observed in the number of

in Ewing sarcoma cells

colonies formed, whereas there was a significant difference in

SPRY1 has been described to inhibit MAPK/ERK pathway, which

the size of the individual colonies No significant

is one of the most relevant proliferative pathways in cancer. For

differences in anchorage-independent growth were observed in

that reason we investigated the effect of SPRY1 induction on ERK

cells transfected with the empty vector when treated accord-

activation mediated by serum. As shown in SPRY1

ingly (Supplementary Figure 2B).

induction reduced the levels of phospho-ERK both in low (1%) and

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz et al

Figure 3. SPRY1 re-expression impairs Ewing sarcoma cell clonogenicity, anchorage-independent growth, migration and invasion of Ewingsarcoma cells. (a) A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were platted in triplicates at low densities and treated with

or without doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml) for 9 days. Colony formation was measured by crystal violet staining. Pictures show representative wells

of one out of three independent experiments. Graphs depict a quantification of absorbance measured after cell de-staining (one

representative experiment out of three performed) (mean ± s.d.). Clonogenic growth is significantly impaired in all three cell lines on SPRY1

re-expression (*P o0.05, **Po0.01 and ***Po0.005). (b) A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were platted in triplicatein soft agar and cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml) during 25 days and subsequently stained with crystal

violet. Pictures show representative images of sphere formation taken at the end of the experiment. Graphs depict the mean area per particleafter 25 days (mean ± s.d.). SPRY1 re-expression inhibits sphere formation in all three cell lines (3 independent experiments) (*Po0.05,

**P o0.01 and ***Po0.005). (c) A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were platted in triplicates and treated with

or without doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml) for 72 h. A ‘wound gap' was created by scratching the cell monolayer using a micropipette tip. Pictures

depict the healing of the gap as a consequence of cell migration at the beginning, middle and end of the experiments. Relative woundclosure for each cell line at the end of the experiment is stated in percentages. Images show a representative experiment out of threeperformed. (d) A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were incubated in the absence or presence of doxycycline (DOX,

1 μg/ml) during 48 h, to induce the expression of SPRY1 protein. Afterwards, cells were starved for another 24 h. Next, they were placed in the

upper compartment of a transwell and allowed to migrate through the membrane in response to serum. Migrating cells were quantified

by crystal violet staining. Figure shows mean ± s.d. of two experiments performed in triplicate. Data are shown as arbitrary units of absorbance

(abs) (*P o0.05 and ***Po0.005).

standard (10%) serum conditions. Next, we explored the effect of

Consistently, FGFR inhibition through any of the four FGF

SPRY1 induction on the ERK activation mediated by basic FGF

inhibitors severely impairs clonogenic growth of A673, SKNMC

(bFGF), an established and potent RAS-activating growth factor.

and POE Ewing sarcoma cell lines

Using bFGF stimulation we observed a similar effect on ERK

As POE cells exhibited high sensitivity toward this FGFR

activation in the three Ewing cell lines.

inhibiton compared with the other cells tested (Supplementary

Collectively, these results indicate that EWS-FLI1-mediated SPRY1

Table 2), we chose this cell line to perform in vivo experiments to

repression in Ewing sarcoma cells contributes to the activation of

test whether PD-74 has an antitumoral effect in a xenograft model

MAPK/ERK pathway and thus to the malignant features observed.

in mice. As shown in PD-74 treatment significantlyinhibited tumor growth (P = 0.004) of Ewing sarcoma xenografts.

These tumors showed an 50% decrease in the number of

FGFR inhibitors mimic the effects of SPRY1 re-expression.

mitoses (P = 0.001) along with a 40% increase in the number

As SPRY1 proved to be capable of inhibiting ERK phosphorylation,

of apoptotic cells per high-power field (P = 0.001) when comparing

especially when the FGF pathway was activated, we assessed

vehicle versus PD-74 treatment. Moreover, Ki-67 staining for

the effect of four FGFR inhibitors (PD-173074 [PD-74], PD-166866

proliferation showed a significant reduction in the number

[PD-66], SU5402 [SU54] and NVP-BGJ398 [BG-98]) on Ewing

of Ki67-positive cells in the tumor samples treated with PD-74

sarcoma cells (A673, SKNMC, SKES, RDES and POE), in order

to test whether FGFR inhibition can mimic SPRY1 effect on Ewing

To confirm whether PD-74 had an antitumoral effect in other

cell lines. Complementary to our previous finding that bFGF

Ewing sarcoma cell lines we performed an in vivo experiment

can induce proliferation in Ewing sarcoma cell lines (that is, A673,

using SKES cells, which presented less sensitivity to it in vitro

SKNMC and POE we observed that FGFR inhibition

. As shown in Supplementary Figure S4A, PD-74 had

reduces proliferation of these Ewing sarcoma cells

a dose-dependent effect on SKES xenograft growth in mice,

whereas it did not affect normal cells such as fibroblasts (IMR90).

with 20 mg/kg being the most effective dose (P = 0.005). Again,

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcomaF Cidre-Aranaz et al

Figure 4. SPRY1 inhibits MAPK pathway in Ewing sarcoma cells by inhibiting ERK phosphorylation induced by bFGF or serum. A673/TR/SPRY1,SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were incubated in the absence or in the presence of doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml) during 48 h, to

induce the expression of SPRY1 protein. Afterwards, cells were starved for an extra 24 h (1% FBS) and finally stimulated for 15 min with 10%

FBS or bFGF (bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor) (10 ng/ml) where indicated. SPRY1, phospho-ERK (pERK), ERK and EWS-FLI1 proteins were

detected by specific antibodies. Anti-tubulin was used as a control for loading and transferring. SPRY1 re-expression is capable of inhibiting

ERK phosphorylation induced by bFGF or serum in all three cell lines. Graphs depict densitometries corresponding to the western blottingbands showing pERK/total ERK ratios in percentage versus cells cultured in the absence of doxycycline (control). The figure shows one

representative experiment out of three performed.

we observed a significant reduction of the number of mitoses

of SPRY1 in situ could be associated with clinical outcome in Ewing

(P = 0.01) and a significant increase in the number of apoptotic

sarcoma patients.

cells per high-power field (P o 0.001) on treatment with PD-74

First, SPRY1 mRNA levels were examined in a cohort of 117

(20 mg/kg) (Supplementary Figure S4B). Similarly, we detected

Ewing sarcoma samples studied with gene expression micro-

significantly less Ki-67 positive cells on treatment of with PD-74

arrays and compared them with published microarray data

(P o 0.01) (Supplementary Figure S4B).

sets comprising 24 different solid tumor types.This analysis

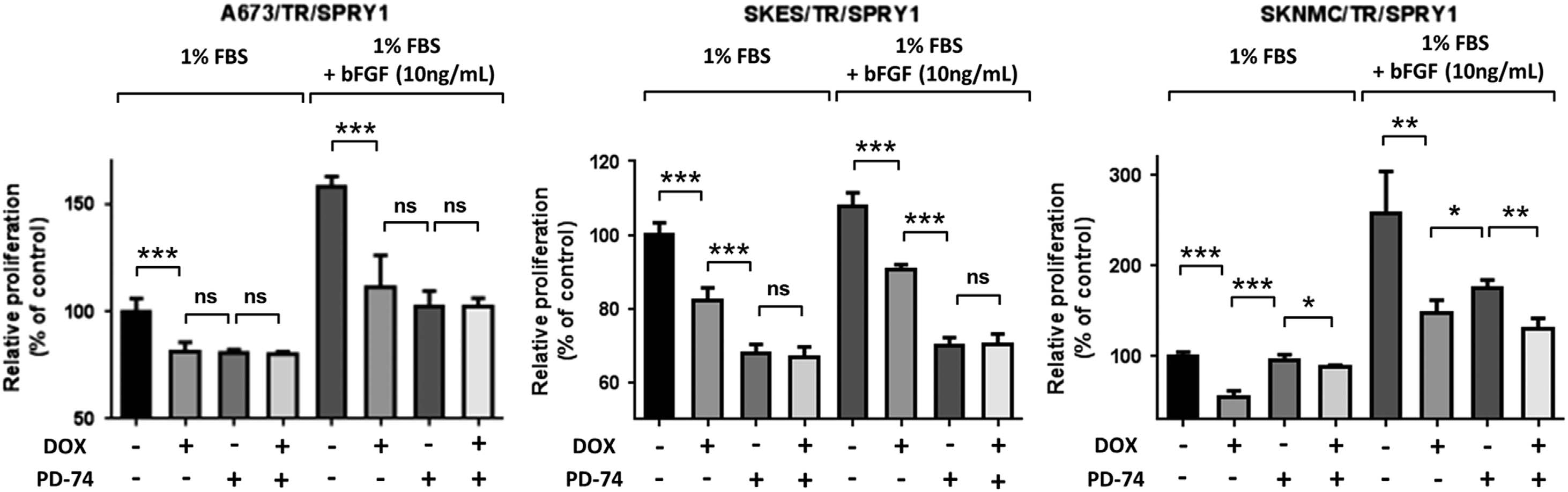

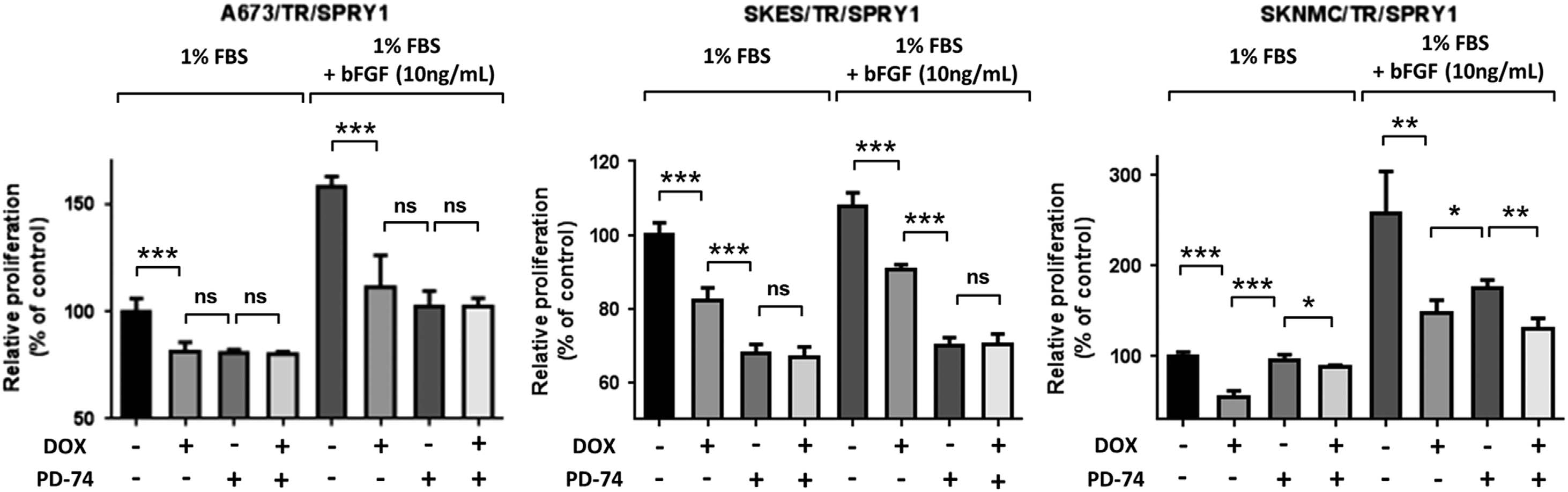

We next explored the combined effect of FGFR inhibition and

revealed that Ewing sarcoma range among the ones with the

SPRY1 re-expression. SPRY1 was re-expressed in the three Ewing

lowest SPRY1 expression although in in situ tumors

sarcoma cell lines and they were concomitantly treated with either

there was more heterogeneity in the SPRY1 mRNA levels as

bFGF or PD-74 alone or a combination of both

compared with Ewing sarcoma cells in culture (

In analogy to the results presented in SPRY1 significantly

Moreover, there was statistically less SPRY1 expression in Ewing

inhibited cell proliferation induced by bFGF in the three cell lines

sarcoma cell lines as compared with primary tumors. In fact, all

studied. Moreover, the effect of SPRY1 re-expression and PD-74

cell lines except for one exhibited less SPRY1 expression than

on cell proliferation was similar in A673 and SKNMC cells

the median sample of primary tumors. In contrast, there was no

Furthermore, when the three cell lines were treated

statistical difference in LOX, NR0B1 and CD99 expression in cell

with other FGF inhibitors (BG98, PD-66 and SU54), two of them

lines when compared with primary tumors

(BG98 and PD-66) were able to significantly further reduce the

Next, we analyzed the correlation between SPRY1 levels in

proliferation beyond the effect of SPRY1 alone (Supplementary

primary tumors and clinical outcome in a cohort of 162 Ewing

Figure S5). However, when SPRY1 was re-expressed concomitantly

sarcoma patientsThe median expression value of SPRY1 was

with any of the three new inhibitors tested, none of them

used as a cutoff to define moderate and low SPRY1 expression

produced a further impairment in proliferation on any of the cells

levels. Using this cutoff, moderate SPRY1 expression levels

tested, which is in agreement with what was previously observed

were significantly associated with a better overall survival

with PD-74 (Supplementary Figure S5).

(5-year overall survival 0.70 vs 0.38, P = 0.002; log-rank test)and event-free survival (5-year event-free survival 0.72 vs 0.45,P = 0.0015; log-rank test) (Interestingly,

SPRY1 expression positively correlates with improved overall

low SPRY1 levels were associated with a higher risk for

survival of Ewing sarcoma patients

the presence of metastasis at diagnosis (P = 0.002, Fisher's

Our results indicate that SPRY1 repression leads to a constitutive

exact test) Collectively, these results strongly

activation of MAPK/ERK pathway in response to external stimuli

support a relationship between the levels of SPRY1 and Ewing

such as bFGF. Thus, we wondered whether the expression levels

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz et al

Figure 5. FGFR inhibitors block Ewing sarcoma cell line proliferation. (a) Four FGFR inhibitors, namely PD-173074 (PD-74), PD-166866 (PD-66),

SU5402 (SU54) and NVP-BGJ398 (BG-98), inhibit A673, SKNMC, POE, RDES and SKES Ewing cell growth in vitro in a dose-dependent manner,whereas normal cells (IMR90 fibroblasts) remained unaffected. PD-74 proved to be most effective in four out of five Ewing sarcoma cell lines

tested. Cells were grown in 10% FBS conditions and cell proliferation was measured after 72 h using a Resazurin assay. (b) PD-173074 (PD-74),

PD-166866 (PD-66), SU5402 (SU54) and NVP-BGJ398 (BG-98) impair A673, SKNMC and POE Ewing sarcoma cells clonogenic growth in vitrowhen cells are grown at 5% FBS for 10–12 days. (c) C.B17/SCID mice were injected with POE cells and randomly split in groups. Each group

was treated intraperitoneally once a day with PD-74 or placebo. The figure shows the evolution of tumor volume (mean ± s.e.m. of six to eight

animals per group) versus time. PD-74 treatment significantly inhibits tumor growth (P = 0.004) of Ewing sarcoma xenografts.

(d) Immunohistochemistry images of tumors obtained in the in vivo experiments. Tissue sections were stained with Ki-67 to detectproliferation and cleaved caspase 3 to detect apoptosis. The graphs show how PD-74 treatment reduces the number of mitoses (P = 0.001)

and increases the number of apoptotic cells per field (P = 0.001). Ki-67 staining and graph show a reduction in the number of Ki67-positive

(++ or +) cells when treated with PD-74 (P o0.01).

SPRY1 promoter directly (Supplementary Figure S6). Interestingly,

EWS-ETS fusion proteins have a central role in the pathogenesis

on EWS-FLI1 knockdown there is an increase of H3K27ac marks

of Ewing sarcoma by regulating the expression of other key

located at the putative SPRY1 promoter comprising SPRY1 exon 1

factors. In this sense, the identification of these regulated genes

and intron 1 (Supplementary Figure S6). This suggests an epigenetic

may help characterize the pathways involved in Ewing sarcoma

mechanism of SPRY1 regulation involving histone modifica-

pathogenesis and aggressiveness, and to therefore open new

tions, instead of a direct binding of EWS-FLI1 to the SPRY1

opportunities for targeted

promoter. Moreover, there were no significant differences in

In this study, we showed that SPRY1, a member of the Sprouty

the percentage of SPRY1 CpG islands' methylation on modula-

family of proteins, is repressed by EWS-FLI1 and is not expressed

tion of EWS-FLI1 expression levels.Accordingly, we propose

in established Ewing sarcoma cell lines. The exact mechanism

that the actual mechanism underlying SPRY1 regulation in Ewing

through which EWS-FLI1 regulates SPRY1 is still unknown. However,

sarcoma may be different from the one operating in other

analysis of two independent chromatin immunoprecipitation

tumors where SPRY1 downregulation is associated with promo-

sequencing studiesindicates that EWS-FLI1 does not bind to

ter methylation.

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcomaF Cidre-Aranaz et al

Figure 6. bFGF induces proliferation of Ewing sarcoma cells, which can be antagonized by FGFR inhibition. A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were incubated in the absence or in the presence of doxycycline (DOX, 1 μg/ml), to induce the expression of

SPRY1 protein, and were concomitantly cultured with 1% FBS, bFGF (10 ng/ml), PD-173074 (PD-74, 5 μM) or a combination of bFGF and PD-74

where indicated. Cell proliferation was measured after 72 h using the Resazurin assay. Graphs depict one independent experiment (mean ± s.d.)

out of three performed. SPRY1 re-expression and PD-74 inhibit cell proliferation-induced serum or bFGF treatment (*Po0.05 and **Po0.005, ns,

Figure 7. SPRY1 expression is positively correlated with improved overall survival of Ewing sarcoma patients. (a) SPRY1 mRNA expressionlevels in 24 different solid tumor entities as determined by Affymetrix HG-U133plus2.0 DNA microarrays. Data were retrieved from the GeneExpression Omnibus (GEO) or the European bioinformatics Institute (EBI) and simultaneously normalized by RMA using brain array CDF files

(v17, ENTREZG) as previously described.Data are represented as medians with boxes representing the interquartile range. Whiskers indicatethe 10th and 90th percentile of the data. The number of analyzed samples is given in parentheses. Ewing sarcoma tumors are shown in gray.

ATRT, atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor; Ca-, carcinoma; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; RMS,rhabdomyosarcoma. (b) Relative expression of SPRY1 as compared with other EWS-FLI1 target genes (LOX and NR0B1) and CD99 in 15individual Ewing sarcoma cell lines versus 117 primary Ewing sarcoma samples (all Affymetrix HG-U133Plus2.0 microarrays). Data wereretrieved from the GEO (accession codes: GSE8596, GSE36133, GSE70826 and GSE34620) and simultaneously normalized by RMA usingbrainarray CDF files (v17, ENTREZG) as previously described.Unpaired two-tailed Student's T-test. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival estimates (overall

survival) in the Ewing sarcoma patient cohort. Patients were classified as being either SPRY1 low or moderate (cutoff: median SPRY1

expression; P = 0.002, log-rank test). (d) Graph depicts the relapse-free survival probability versus SPRY1 level of expression (low or moderate,

cutoff: median SPRY1 expression). SPRY1 expression positively correlates with improved relapse-free probability (P = 0.0015, log rank test).

(e) Graph shows the percentage of cases with metastasis at diagnosis versus SPRY1 level of expression (low or moderate, cutoff: median SPRY1expression). Moderate SPRY1 expression correlates with lower risk of metastasis at diagnosis (P = 0.002, Fisher's exact test).

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz et al

As SPRY1 has been shown to be a potent negative regulator of

however, it can be hypothesized that SPRY1 levels remain variable

the RAS/MAPK/ERK signaling we hypothesized that

in tumors, and that the harsh conditions of in vitro cell culture

SPRY1 may act as a tumor suppressor gene in Ewing sarcoma.

favor the growth of cells with lower SPRY1 levels during

In support of this notion, induction of SPRY1 in three independent

establishment of Ewing sarcoma cell lines. In fact, established

Ewing sarcoma cell lines significantly impaired cell prolifera-

Ewing sarcoma cell lines harbor a much higher rate of STAG2, TP53

tion and migration. This is consistent with a tumor supressor

and CDKN1A mutations than that observed in primary tumors

function of SPRY1 in Ewing sarcoma and in agreement with

suggesting that cells derived from more aggressive

previous reports showing that SPRY1 overexpression impairs cell

tumors are favored in

growth, proliferation, migration and invasion of a variety of cancer

Ewing sarcoma is a very aggressive pediatric malignancy

cell lines including ovarian carcinoma, breast cancer, lung

in which primary metastasis is the most unfavorable risk factor,

adenocarcinoma, colon carcinoma or osteosarcoma.

very often leading to fatal outcome despite highly intense and

Our results also demonstrate that SPRY1 downregulation

toxic Here we show that low SPRY1 expression levels

is necessary for bFGF-mediated proliferation and activation of

correlate with a significantly worse overall and event-free survival

RAS/MAPK/ERK pathways in Ewing sarcoma cells. Thus, SPRY1

in a large cohort of Ewing sarcoma patients. More interestingly,

re-expression in the three Ewing sarcoma cell lines used in this

primary tumors displaying low levels of SPRY1 were more

study impaired cell proliferation and ERK phosphorylation induced

frequently observed in patients harboring metastasis at diagnosis.

by bFGF. bFGF is known to mediate proliferation, migration and

This is compatible with a more aggressive behavior of SPRY1-low

differentiation in various cellular and FGF-regulated

tumors and in agreement with the results observed in the in vitro

pathways have a preponderant role in cancer (reviewed in Touat

experiments. We speculate that tumors expressing low levels

et al.Notably, an important role for FGF-dependent pathways

of SPRY1 would present a higher response to external growth

in Ewing sarcoma pathogenesis is emerging. We have recently

factor stimulation and thus exhibit higher rates of proliferation

reported that bFGF increases proliferation of Ewing sarcoma cells

and migration, making them more aggressive. This may have

in vitro, and that EGR2, which is a downstream component of the

a potential clinical application, as SPRY1 has been recently

FGF pathway, is an EWS-FLI1-induced target gene.Other studies

proposed as a possible tissue biomarker to differentiate aggressive

have demonstrated that bFGF regulates motility and invasion of

from indolent prostate carcinomas.

Ewing sarcoma cells in the bone microenvironmentIn agreement,

In summary, our data provide evidence that EWS-FLI1-mediated

Agelopoulos et al.recently showed that constitutive knockdown of

SPRY1 downregulation is an important mechanism in Ewing

FGFR1 abolishes engraftment of Ewing sarcoma xenografts in mice.

sarcoma pathogenesis. Moreover, our results strongly suggest that

Interestingly, over 75% of Ewing sarcoma biopsy samples present

bFGF-mediated stimulation of cell proliferation could be more

moderate-to-high levels of FGFR1 palthough

important than initially acknowledged in Ewing sarcoma, and that

activating FGFR1 mutations are extremely rare in this

FGFR inhibitors may constitute promising drugs for treatment

In light of these facts and our new results, we propose that

of Ewing sarcoma patients.

constitutive activation of FGFRs and downstream pathwaysare key contributors to the pathogenesis of Ewing sarcoma, andthat EWS-FLI1-mediated suppression of the negative-feedback

MATERIALS AND METHODS

regulator SPRY1 constitutes a major mechanism for sustained

FGFR phosphorylation and thus unrestrained FGF-induced signal

A673/TR/shEF cells, which have been described elsewhere,were cultured

transduction and tumor progression. In synopsis, our results

in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10%

support that SPRY1 downregulation is pre-requisite for enhanced

proliferation and migration of Ewing sarcoma cells induced

100 μg/ml zeocin and 3 μg/ml blasticidin. Induction of

by either EWS-FLI1 itself, external growth factor stimulation or

a small hairpin RNA against EWS-FLI1 was started by the addition

a combination of both as part of an autocrine loop.

of 1 μg/ml doxycycline (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Ewing sarcoma cell lines

The importance of this pathway in Ewing sarcoma pathogenesis

A4573, TC-71, RD-ES, POE and TTC-466, and the normal fibroblast cell

is additionally illustrated by FGFR-inhibition-mediated impairment

line IMR90 were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium, SK-PN-DW and SKNMCwild-type cells were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium,

of cell proliferation and clonogenic growth of Ewing sarcoma cells

and wild-type A673 and SKES cells were maintained in Dulbecco's

in vitro. Interestingly, the search for more efficient and specific

modified Eagle's medium. All media were supplemented, if not other-

FGFR inhibitors is an active field in the pharmaceutical industry,

wise stated, with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK)

as FGF signaling pathways is one of the most commonly mutated

and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All cells were routinely tested

systems in cancer.In this regard, the Ewing sarcoma research

for mycoplasma contamination (Mycoalert mycoplasma detection kit,

community can take advantage of the development of these new

Lonza #LT07-318, Basel, Switzerland) and were authenticated by short

drugs, some of which are being tested in clinical trials with

tandem repeats profiling at the Genomic Facility at Biomedical Research

promising results, particularly in tumors harboring aberrant FGFR

Institute, CSIC, Madrid, Spain).

signaling (reviewed in Touat et al.).

FGFR signaling can be aberrantly activated in Ewing sarcoma

Establishment of Ewing sarcoma cell lines stably expressing

either through downregulation of SPRY1 (as observed in most

doxycycline-inducible SPRY1 cDNA

cases), through overexpression of FGFRs (as observed in subset

The complete coding region of SPRY1 was reverse transcription–PCR

of pa), or very rarely through somatic mutaFor

amplified from A673/TR/shEF cells stimulated with doxycycline using primers

that reason, we anticipate that Ewing sarcoma patients may benefit

5′-GCGGTCGACGAGATCACTACACATGGATCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGGCGGCC

from targeted drugs directed against FGFRs or its downstream

GCTCATCATCATGATGGTTTACCCTGACC-3′ (reverse). The amplified fragments

targets. In support of this notion, Agelopoulus et reported on

were digested with SalI and NotI, cloned into the pENTR2B plasmid

a single patient affected by relapsed Ewing sarcoma, who was

(Invitrogen) and transferred by recombination to the lentiviral doxycycline-

treated with an FGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (ponatinib), which led

inducible plasmid pLenti4-TO-V5-DEST (Invitrogen). Next, A673/TR, SKES/TR

to a reduction in 18-FDG-PET activity and thus glucose uptake by

and SKNMC/TR Ewing sarcoma cells expressing the tetracycline repressorconstitutively were infected with lentiviruses containing the SPRY1 cDNA.

Control cells were infected with empty lentiviral vector. Stable clones were

Interestingly, although SPRY1 was undetectable in established

selected with zeocin (100 μg/ml). Induction of SPRY1 was assayed by western

Ewing sarcoma cell lines, its levels in primary tumors were variable.

blottings on doxycycline (1 μg/ml) stimulation. Clones displaying the highest

Currently, the reasons for the differences between SPRY1 levels

levels of protein expression on doxycycline stimulation were chosen for

in established cell lines and tumors in situ are still unknown;

additional studies.

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcomaF Cidre-Aranaz et al

Reverse transcription–quantitative PCR

Reverse transcription–quantitative PCR conditions, primer and TaqMan

Cells were pre-treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 24 h to induce the

probe sequences specific for EWS-FLI1, LOX, NR0B1(DAX1) and TBP were

expression of SPRY1 protein. Next, they were starved (0.5% FBS) for

described TaqMan probes for SPRY1, 2, 3 and 4 were

another additional 24 h in the same doxycycline conditions. Then, 3 × 105

purchased to Life Technologies (San Diego, CA, USA). Reactions were run

pretreated cells were re-suspended in 2 ml of medium containing 0.5%

on a RotorGene 6000 (Corbett Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia) and

tetracycline-free FBS and placed in the upper chamber of transwells

relative expression was calculated as previously described

(8.0 μm pore size) (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) following theprocedure described

Western blot analysis and antibodies

Procedure was described elsewhere.Primary antibodies were purchased to

Cells were plated by triplicate (5 × 105 cells per 60 mm dishes) in soft agar

the following companies: anti-FLI1 polyclonal antibody from NeoMarkers

and cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline during 25 days.

(#RB-9295-P) (Fremont, CA, USA), anti-SPRY1 monoclonal antibody from

Fresh culture medium was added to plates every 2–3 days. At the end of the

Santa Cruz Biotechnology (#100861) (Dallas, TX, USA), Tubulin monoclonal

experiment, three random fields for each plate were photographed. The

antibody from Sigma Aldrich (#T9026) (St Louis, MO, USA), and anti-Phospho-

number of colonies per field and its respective area were calculated using

p44/42 (pERK, #9106) and anti-p44/42 (totalERK, #9102) were from Cell

NIH ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Signaling (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-mouse (#2055) and anti-rabbit IgG (#2054)horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

A673/TR/SPRY1, SKES/TR/SPRY1 and SKNMC/TR/SPRY1 cells were platedin triplicates at 0.5 × 103, 1 × 103 and 2 × 103 cells per well, respectively,

Bromodeoxyuridine proliferation assay

in a 24-well plate. They were subsequently treated with or without

Cells were plated in octaplicates (1 × 103 cells per well in 96 multi-well

doxycycline (1 μg/ml) and maintained for 9 days in culture media

plates) and cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (1 μg/ml)

supplemented with 5% tetracycline-free FBS. Media was changed every

for 72 h in 10% or 1% tetracycline-free FBS (Clontech). Thereafter,

3–4 days and doxycycline treatment was continued. Finally, colonieswere fixed, stained with crystal violet and photographed. Cells were

bromodeoxyuridine chemiluminescent assay (Roche, Basel, Switzerland)

de-stained using 50% ethanol 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 4.2. Absorbance was

was performed according to manufacturer's instructions. Chemiluminescence

quantified at 560 nm using an Infinite M200 (Tecan) microplate reader.

was measured using an Infinite M200 (Tecan, Mannerdorf, Switzerland)microplate reader.

Tumor xenografts in micePOE and SKES cells were resuspended in PBS/matrigel (BD Biosciences,

Resazurin proliferation assay

Le Pont de Claix Cedex, France) (1:1) and injected (8 × 106/200 μl)

Cells were plated in octaplicates (2.5 × 103 cells per well in 96 multi-well

subcutaneously in the flanks of 6-week old C.B17/SCID male and female

plates) and concomitantly cultured in the presence or absence

mice (Charles River Laboratories, Lyon, France). When tumor volume

of doxycycline (1 μg/ml) and stimuli (1% or 10% tetracycline-free FBS

reached 150 mm3 (calculated with the formula length × width × depth ×

or 10 ng/ml bFGF) for 72 h. For bFGF-inhibitor testing, cells were grown at

0.5432), mice were injected intraperitoneally once a day with the indicated

10% FBS for 72 h in the presence of PD-173074 (PD-74) (Selleckchem,

dose of PD-173074 (5, 10 or 20 mg/kg) dissolved in 10% dimethyl

Houston, TX, USA), PD-166866 (PD-66) (#PZ0114, Sigma Aldrich), SU5402

sulfoxide–90% Corn Oil (Sigma) or placebo in the control group. Tumor

(SU54) (#S7667, Selleckchem) or NVP-BGJ398 (BG-98) (#S2183, Selleck-

growth was monitored with a caliper and mice were killed when tumors

chem). Thereafter, Resazurin (#R7017, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the

reached a volume of 1500 mm3. Experiments were carried out in

media at 0.15 μg/ml and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Fluorescence was

accordance with recommendations of the European Community (86/609/EEC), the French Competent Authority, the UKCCCR guidelines (guidelines

recorded using a 560-nm excitation/590-nm emission filter set in an

for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research), the Ethics

Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan).

Committee at ISCIII (CBA #64_2015-v2) and the Spanish CompetentAuthority (PROEX 009/16).

xCELLigence proliferation assayCell proliferation was assayed in real time with a bioelectric xCELLigence

Histology and immunohistochemistry

instrument (Roche/ACEA Biosciences). In each well, 3–4 × 103 Ewing

Immunohistochemistry analyses were done on formalin-fixed, paraffin-

sarcoma cells were seeded in 200 μl media containing 10% tetracycline-

embedded xenograft tumors. All tissue samples were collected at

free FBS and treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) or vehicle (triplicate wells/

the Institute of Pathology of the LMU Munich for immediate immunohis-

group). Cellular impedance was measured periodically and media with

tochemistry staining, for which 4-μm sections were cut. Antigen retrieval was

or without doxycycline were changed once after 72 h.

carried out by microwave treatment in Dako target retrieval solution (S2369).

The following primary antibodies were used: polyclonal rabbit anti-cleaved-caspase-3 (1:100 at room temperature for 60 min; #9661, Cell Signaling) or

Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle

monoclonal rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:200 at room temperature for 60 min;

Cells were treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 72 h to induce the

#275R-15 clone SP6, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA). The ImmPRESS Reagent

expression of SPRY1 and fixed with 70% ethanol for 24 h at 4 °C. Next, they

Kit anti-rabbit IgG (MP-7401, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was

were stained with a solution of 0.005% (w/v) of propidium iodide and

used for antigen detection. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin

RNAase A as recommended by the manufacturer (BD Biosciences, San José,

Gill's Formula (H-3401, Vector Laboratories). The average number of positive

CA, USA) and were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. They were then analyzed

cells was determined by analysis of 10 high-power fields (×40 magnification)

in a MACS Quant Analyzer flow cytometer (Miltenyi Biotec, Cologne,

for each xenograft tumor. Statistical differences between groups were

calculated with an unpaired tow-tailed Student's T-test.

Wound-healing assay

A total of 162 Ewing sarcoma patients with available clinical data and

Cells were plated in triplicates (2–4 × 104 cells per well in 24 multi-well

tumor samples were used in this study. This cohort consists of 117 Ewing

plates) and were incubated with or without doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for 72 h

patients for which gene expression profiles in primary tumors were

before the assay. At the end of this period, a ‘wound gap' in the cell

analyzed with HG-U133 plus2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA,

monolayer was created using a micropipette tip. The healing of the gap

USA) (Gene Expression Omnibus accession number: GSE34620) and 45

by cell migrating was monitored by photographing the progress every

patients whose gene expression profiles were studied with Uniset Human

6–12 h until wound closure. Quantification of relative cell migration is

20 K I microarrays (Codelink Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

All patients received a similar protocol treatment.

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcoma

F Cidre-Aranaz et al

Statistical analysis

12 Prieur A, Tirode F, Cohen P, Delattre O. EWS/FLI-1 silencing and gene profiling

For a single comparison of two groups, two-tailed Student's t-test was used

of Ewing cells reveal downstream oncogenic pathways and a crucial role

and a normal distribution was assumed. Variances between the groups

for repression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3. Mol Cell Biol 2004;

that were compared were similar. For animal studies, the sample size was

24: 7275–7283.

estimated to be six to eight mice considering a signal/noise ratio of 1.6–1.8,

13 Agra N, Cidre F, Garcia-Garcia L, de la Parra J, Alonso J. Lysyl oxidase is

80% power, assuming a 5% significance level and a two-sided test.

downregulated by the EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein and its propeptide domain displays

No investigator blinding was done during the experiment. For in situ

tumor supressor activities in ewing sarcoma cells. PLoS One 2013; 8: e66281.

studies including overall survival and relapse-free survival probabilities,

14 Navarro D, Agra N, Pestana A, Alonso J, Gonzalez-Sancho JM. The EWS/FLI1

log-rank test was used. For proportions, Fisher's exact test was used. For all

oncogenic protein inhibits expression of the Wnt inhibitor DICKKOPF-1 gene and

analyses, the level of significance was set at P = 0.05 and the variance was

similar between groups. All statistical calculations were performed using

31: 394–401.

the GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego,

15 Hahm KB, Cho K, Lee C, Im YH, Chang J, Choi SG et al. Repression of the gene

encoding the TGF-beta type II receptor is a major target of the EWS-FLI1oncoprotein. Nat Genet 1999; 23: 222–227.

16 Minowada G, Jarvis LA, Chi CL, Neubuser A, Sun X, Hacohen N et al. Vertebrate

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Sprouty genes are induced by FGF signaling and can cause chondrodysplasia

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

when overexpressed. Development 1999; 126: 4465–4475.

17 Guy GR, Wong ES, Yusoff P, Chandramouli S, Lo TL, Lim J et al. Sprouty: how does

the branch manager work? J Cell Sci 2003; 116: 3061–3068.

18 Christofori G. Split personalities: the agonistic antagonist Sprouty. Nat Cell Biol

2003; 5: 377–379.

FC-A, LG-G, JCL, AS, PG-M, SEL-P, SM and JA are supported by Asociación Pablo

19 Zhao Z, Zuber J, Diaz-Flores E, Lintault L, Kogan SC, Shannon K et al. p53 loss

Ugarte and Miguelañez SA, ASION-La Hucha de Tomás, Fundación La Sonrisa de Alex

promotes acute myeloid leukemia by enabling aberrant self-renewal. Genes Dev

and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI12/00816 and Spanish Cancer Network RTICC

2010; 24: 1389–1402.

RD12/0036/0027). TGPG is supported by a grant from ‘Verein zur Förderung von

20 Fritzsche S, Kenzelmann M, Hoffmann MJ, Muller M, Engers R, Grone HJ et al.

Wissenschaft und Forschung an der Medizinischen Fakultät der LMU München

Concomitant down-regulation of SPRY1 and SPRY2 in prostate carcinoma. Endocr

(WiFoMed)', the Daimler and Benz Foundation in cooperation with the Reinhard

Relat Cancer 2006; 13: 839–849.

Frank Foundation, by LMU Munich's Institutional Strategy LMUexcellent within the

21 Lo TL, Yusoff P, Fong CW, Guo K, McCaw BJ, Phillips WA et al. The ras/mitogen-

framework of the German Excellence Initiative, the ‘Mehr LEBEN für krebskranke

activated protein kinase pathway inhibitor and likely tumor suppressor proteins,

Kinder—Bettina-Bräu-Stiftung', the Walter Schulz Foundation, the Fritz Thyssen

sprouty 1 and sprouty 2 are deregulated in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2004; 64:

Foundation (FTH-40.15.0.030MN) and by the German Cancer Aid (DKH-111886 and

DKH-70112257). The ‘Genetics and Biology of Cancers' team (TGPG, DS and OD) is

22 Kwabi-Addo B, Ren C, Ittmann M. DNA methylation and aberrant expression

supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale Contre Le Cancer (Equipe labellisée).

of Sprouty1 in human prostate cancer. Epigenetics 2009; 4: 54–61.

This work was also supported by the European PROVABES, ASSET and EEC FP7 grants.

23 Kwabi-Addo B, Wang J, Erdem H, Vaid A, Castro P, Ayala G et al. The expression

We also thank the following associations for their invaluable support: the Société

of Sprouty1, an inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor signal transduction,

Française des Cancers de l'Enfant, Courir pour Mathieu, Dans les pas du Géant, Olivier

is decreased in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 4728–4735.

Chape, Les Bagouzamanon, Enfants et Santé and les Amis de Claire. We thank Dr SNavarro (University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain) and Dr TJ Triche (Children's Hospital

24 Masoumi-Moghaddam S, Amini A, Ehteda A, Wei AQ, Morris DL. The expression

Los Angeles, Los Angeles, USA) for providing us with Ewing sarcoma cell lines A4573

of the Sprouty 1 protein inversely correlates with growth, proliferation, migration

and TTC-466, respectively.

and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. J Ovarian Res 2014; 7: 61.

25 Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S et al.

The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer

drug sensitivity. Nature 2012; 483: 603–607.

26 Grunewald TG, Bernard V, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P, Raynal V, Surdez D, Aynaud MM

1 Mackintosh C, Madoz-Gurpide J, Ordonez JL, Osuna D, Herrero-Martin D.

et al. Chimeric EWSR1-FLI1 regulates the Ewing sarcoma susceptibility gene EGR2

The molecular pathogenesis of Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Biol Ther 2010; 9:

via a GGAA microsatellite. Nat Genet 2015; 47: 1073–1078.

27 Willier S, Butt E, Grunewald TG. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signalling in cell

2 Grohar PJ, Helman LJ. Prospects and challenges for the development of new

migration and cancer invasion: a focussed review and analysis of LPA receptor

therapies for Ewing sarcoma. Pharmacol Ther 2013; 137: 216–224.

gene expression on the basis of more than 1700 cancer microarrays. Biol Cell

3 Ladenstein R, Potschger U, Le Deley MC, Whelan J, Paulussen M, Oberlin O et al.

2013; 105: 317–333.

Primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcoma: results of the Euro-EWING

28 Postel-Vinay S, Veron AS, Tirode F, Pierron G, Reynaud S, Kovar H et al. Common

99 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3284–3291.

variants near TARDBP and EGR2 are associated with susceptibility to Ewing

4 Zhu L, McManus MM, Hughes DP. Understanding the biology of bone sarcoma

sarcoma. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 323–327.

from early initiating events through late events in metastasis and disease

29 Cidre-Aranaz F, Alonso J. EWS/FLI1 target genes and therapeutic opportunities

progression. Front Oncol 2013; 3: 230.

in Ewing sarcoma. Front Oncol 2015; 5: 162.

5 Delattre O, Zucman J, Plougastel B, Desmaze C, Melot T, Peter M et al. Gene fusion

30 Bilke S, Schwentner R, Yang F, Kauer M, Jug G, Walker RL et al. Oncogenic ETS

with an ETS DNA-binding domain caused by chromosome translocation in humantumours. Nature 1992; 359: 162–165.

fusions deregulate E2F3 target genes in Ewing sarcoma and prostate cancer.

6 Kovar H. Blocking the road, stopping the engine or killing the driver? Advances in

Genome Res 2013; 23: 1797–1809.

targeting EWS/FLI-1 fusion in Ewing sarcoma as novel therapy. Expert Opin Ther

31 Riggi N, Knoechel B, Gillespie SM, Rheinbay E, Boulay G, Suva ML et al. EWS-FLI1

Targets 2014; 18: 1315–1328.

utilizes divergent chromatin remodeling mechanisms to directly activate

7 Carrillo J, Garcia-Aragoncillo E, Azorin D, Agra N, Sastre A, Gonzalez-Mediero I et al.

or repress enhancer elements in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Cell 2014; 26: 668–681.

32 Tomazou EM, Sheffield NC, Schmidl C, Schuster M, Schonegger A, Datlinger P et al.

tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 2429–2440.

Epigenome mapping reveals distinct modes of gene regulation and widespread

8 Garcia-Aragoncillo E, Carrillo J, Lalli E, Agra N, Gomez-Lopez G, Pestana A et al.

enhancer reprogramming by the oncogenic fusion protein EWS-FLI1. Cell Rep 2015;

DAX1, a direct target of EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein, is a principal regulator of cell-cycle

10: 1082–1095.

progression in Ewing's tumor cells. Oncogene 2008; 27: 6034–6043.

33 Calvisi DF, Ladu S, Gorden A, Farina M, Lee JS, Conner EA et al. Mechanistic

9 Smith R, Owen LA, Trem DJ, Wong JS, Whangbo JS, Golub TR et al. Expression

significance of aberrant methylation in the molecular

profiling of EWS/FLI identifies NKX2.2 as a critical target gene in Ewing's sarcoma.

pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Invest 2007; 117:

Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 405–416.

10 Surdez D, Benetkiewicz M, Perrin V, Han ZY, Pierron G, Ballet S et al. Targeting

34 Macia A, Gallel P, Vaquero M, Gou-Fabregas M, Santacana M, Maliszewska A et al.

the EWSR1-FLI1 oncogene-induced protein kinase PKC-beta abolishes ewing

Sprouty1 is a candidate tumor-suppressor gene in medullary thyroid carcinoma.

sarcoma growth. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 4494–4503.

Oncogene 2012; 31: 3961–3972.

11 Grunewald TG, Diebold I, Esposito I, Plehm S, Hauer K, Thiel U et al. STEAP1

35 Gross I, Bassit B, Benezra M, Licht JD. Mammalian sprouty proteins inhibit cell

is associated with the invasive and oxidative stress phenotype of Ewing tumors.

growth and differentiation by preventing ras activation. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:

Mol Cancer Res 2012; 10: 52–65.

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

SPRY1 is a tumor suppressor in Ewing sarcomaF Cidre-Aranaz et al

36 Mekkawy AH, Pourgholami MH, Morris DL. Human Sprouty1 suppresses growth,

45 Agelopoulos K, Richter GH, Schmidt E, Dirksen U, von Heyking K, Moser B et al.

migration, and invasion in human breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol 2014; 35:

Deep sequencing in conjunction with expression and functional analyses reveals

activation of FGFR1 in Ewing sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 4935–4946.

37 Wiles ET, Lui-Sargent B, Bell R, Lessnick SL. BCL11B is up-regulated by EWS/FLI and

46 Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, Parker M, Le Deley MC, Bahrami A et al. Genomic

contributes to the transformed phenotype in Ewing sarcoma. PLoS ONE 2013;

landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of

STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer Discov 2014; 4: 1342–1353.

38 Liu X, Lan Y, Zhang D, Wang K, Wang Y, Hua ZC. SPRY1 promotes the degradation

47 Kovar H, Jug G, Aryee DN, Zoubek A, Ambros P, Gruber B et al. Among genes

of uPAR and inhibits uPAR-mediated cell adhesion and proliferation. Am J Cancer

involved in the RB dependent cell cycle regulatory cascade, the p16 tumor

Res 2014; 4: 683–697.

suppressor gene is frequently lost in the Ewing family of tumors. Oncogene 1997;

39 Powers CJ, McLeskey SW, Wellstein A. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors

15: 2225–2232.

and signaling. Endocr Relat Cancer 2000; 7: 165–197.

48 Kovar H, Pospisilova S, Jug G, Printz D, Gadner H. Response of Ewing tumor cells

40 Bottcher RT, Niehrs C. Fibroblast growth factor signaling during early vertebrate

to forced and activated p53 expression. Oncogene 2003; 22: 3193–3204.

development. Endocr Rev 2005; 26: 63–77.

49 Gaspar N, Hawkins DS, Dirksen U, Lewis IJ, Ferrari S, Le Deley MC et al. Ewing

41 Chalkiadaki G, Nikitovic D, Berdiaki A, Sifaki M, Krasagakis K, Katonis P et al.

sarcoma: current management and future approaches through collaboration.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 modulates melanoma adhesion and migration through

J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 3036–3046.

a syndecan-4-dependent mechanism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2009; 41: 1323–1331.

42 Yamaguchi F, Saya H, Bruner JM, Morrison RS. Differential expression of two

50 Terada N, Shiraishi T, Zeng Y, Aw-Yong KM, Liu Z, Takahashi S et al. Correlation of

fibroblast growth factor-receptor genes is associated with malignant progression

Sprouty1 and Jagged1 with aggressive prostate cancer cells with different sen-

in human astrocytomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91: 484–488.

sitivities to androgen deprivation. J Cell Biochem 2014; 115: 1505–1515.

43 Touat M, Ileana E, Postel-Vinay S, Andre F, Soria JC. Targeting FGFR signaling

51 Mendiola M, Carrillo J, Garcia E, Lalli E, Hernandez T, de Alava E et al. The orphan

in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 2684–2694.

nuclear receptor DAX1 is up-regulated by the EWS/FLI1 oncoprotein and is highly

44 Kamura S, Matsumoto Y, Fukushi JI, Fujiwara T, Iida K, Okada Y et al. Basic

expressed in Ewing tumors. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 1381–1389.

fibroblast growth factor in the bone microenvironment enhances cell motility and

52 Yue PY, Leung EP, Mak NK, Wong RN. A simplified method for quantifying

invasion of Ewing's sarcoma family of tumours by activating the FGFR1-PI3K-Rac1

cell migration/wound healing in 96-well plates. J Biomol Screen 2010; 15:

pathway. Br J Cancer 2010; 103: 370–381.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited

Oncogene (2016) 1 – 11

Source: http://www.asociacionpablougarte.es/pdf/ayudaISCIII/2016_Oncogene.pdf

36V 14.5Ah eZee Flat BatteryCustomized for Grin Tech Specifications and User Guide 35 cm (13.75") Grin Technologies Ltd.20 E 4th AveVancouver, BC, CanadaV5T 1E8 Copyright © 2012 Congratulations on your purchase of this 36V 14.5Ah lithium manganese ebike battery pack. Our hope is that it provides you with a solid 2-3 years of trouble-free power for your vehicle project.

Magnesium Research 2010; 23 (2): 1-13 Magnesium and cardiovascular system Leviev Heart Center, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomern and the Sackler Facultyof Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, IsraelCorrespondence: M.Shechter, MD, MA, FESC, FACC, FAHA, FACN, Director, Clinical Research Unit, Leviev Heart Center, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, 52621 Tel Hashomer, Israel