Kamagra gibt es auch als Kautabletten, die sich schneller auflösen als normale Pillen. Manche Patienten empfinden das als angenehmer. Wer sich informieren will, findet Hinweise unter kamagra kautabletten.

Psichiatriaedipendenze.it

HEROIN ADDICTION &

Pacini Editore & AU CNS

Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl 2011; 13(2): 5-40

Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or

psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

Icro Maremmani 1, Matteo Pacini 2, Pier Paolo Pani 3, on behalf of the 'Basics on Addiction Group'

1 Vincent P. Dole Dual Diagnosis Unit, Santa Chiara University Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, NPB, University

of Pisa, Italy

2 G. de Lisio Institute of Behavioural Sciences, Pisa, Italy

3 Social-Health Division, Health District 8 (ASL 8) Cagliari, Italy

Opioid dependence is a chronic, relapsing brain disease that causes major medical, social and economic problems to

both the individual and society. This seminar is intended to be a useful training resource to aid healthcare professionals

– in particular, physicians who prescribe opioid pharmacotherapies – in assessing and treating opioid-dependent indi-

viduals. Herein we describe the neurobiological basis of the condition; recommended approaches to patient assessment

and monitoring; and the main principles and strategies underlying medically assisted approaches to treatment, including

the pharmacology and clinical application of methadone, buprenorphine and buprenorphine–naloxone.

Key Words: Tolerance; physical dependence; addiction; clinical assessment; maintenance pharmacotherapies;

methadone; buprenorphine; suboxone.

broader impact on other budgets (e.g., social wel-

fare and criminal-justice services). In addition,

Opioid dependence is a chronic, relapsing opioid dependence affects productivity, due to

brain disease that causes major medical, social unemployment, absenteeism and premature mor-

and economic problems to both the individual tality [111]. In West and Central Europe, there are

and to society. Opioid-dependent individuals are estimated to be between 1 and 1.4 million opiate

subject to substantial health risks including over- users, corresponding to a prevalence of between

dose, transmission of infectious diseases, poor 0.4% and 0.5% of the population.

physical and mental health and frequent hospi-

Given the magnitude of these problems, it

talization [44]. For society as a whole, opioid de- has become crucial to ensure medical practition-

pendence incurs a significant economic burden, ers responsible for treating opioid dependence

both in terms of direct healthcare costs (i.e., treat- have access to evidence-based training pack-

ment and prevention services), and in terms of the ages. This supplement is intended to be a useful

Correspondence: Icro Maremmani, MD; Vincent P. Dole Dual Diagnosis Unit, Santa Chiara University Hospital,

Department of Psychiatry, University of Pisa, Via Roma, 67 56100 PISA, Italy, EU.

Phone +39 0584 790073 Fax +39 0584 72081 E-Mail:

[email protected]

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

how each of these treatment options can be used

Table 1. Actions of morphine [78]

to treat opioid dependence and the main efficacy

Central nervous system depression

and safety considerations that are relevant to the

Respiratory depression (death)

choice of treatment strategy.

2. Neurobiology of opioid dependence

Cough suppression

Pupillary constriction

Nausea and vomiting

2.1. Opioids and their mechanism of action

Increased respiratory tract secretions

2.1.1. What is an opioid?

training resource to aid healthcare professionals

Opium has been used for social and medici-

– in particular, physicians who prescribe opioid nal purposes for thousands of years to produce

pharmacotherapies – in assessing and treating euphoria, analgesia and sleep and to prevent di-

opioid-dependent individuals. It is based upon arrhoea [85]. Several pharmacologically active

the ‘Basics on Addiction' training package de- compounds are derived from the opium poppy

veloped as a collaborative initiative by leading

Papaver somniferum, including morphine, co-

treatment experts in Italy and led by Professor deine, papaverine, thebaine and noscapine [24].

Icro Maremmani (President of EUROPAD) and Opioids is the term given to natural or synthetic

Professor Pier Paolo Pani (President of the Italian drugs that have certain pharmacological actions

Society of Addiction Medicine) on behalf of the similar to those of morphine [84] by the interac-

Basics on Addiction (BoA) Group.

tion with some or all opioid receptors.

In order to optimally treat opioid-dependent

individuals it is first necessary to understand the

2.1.2. Acute opioid effects

neurobiological basis of the condition as a chron-

ic, relapsing disorder. The first article in this sup-

Morphine, the archetypal opioid, is a power-

plement, ‘Neurobiology of opioid dependence', ful analgesic and narcotic, and remains one of the

gives an overview of the effects of opioids on the most valuable analgesics for relief of severe pain

body at the cellular level and the physiological ef- [24]. It also induces a powerful sense of content-

fects of opioids and neurobiological adaptations ment and well-being, which is an important part

to opioids (including tolerance, physical depend- of its analgesic activity, as it reduces the anxiety

ence, withdrawal, craving and relapse). Effective and agitation associated with a painful illness or

treatment of opioid dependence requires thor- injury. Other opioid effects on the central nervous

ough, ongoing assessment of patients to ensure system include respiratory depression, depres-

therapeutic strategies are suited to their individu- sion of the cough reflex, nausea and vomiting and

al needs and circumstances. The second article in pupillary constriction [85]. Morphine also acts

this supplement describes approaches to clinical on the gut wall, reducing intestinal secretion and

assessment and monitoring that should be con- motility and lengthening gut transit time [21].

ducted in drug-dependent individuals to inform The actions of morphine are shown in Table 1.

choices regarding appropriate treatment. The fi-

Following elucidation of the chemical struc-

nal article discusses the main principles, goals ture of morphine at the beginning of the 20th

and strategies underlying medically assisted ap- century [95], many semi-synthetic and totally

proaches to opioid-dependence treatment, the synthetic opioids have been produced (including

unique pharmacological profiles of methadone, methadone, buprenorphine and pethidine) with

buprenorphine and buprenorphine-naloxone, the aim of harnessing the clinically useful proper-

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

Table 2: Effects associated with the main types of opioid receptors [85]

mu (μ, MOP or OP3)

delta (δ DOP or OP2)

kappa (κ, KOP or OP1)

Respiratory depression

Pupil constriction

Reduced GI motility

Physical dependence

+: denotes activity; −: denotes weak or no activity

ties of the opioids without the less desirable side the brainstem, the medial thalamus, the spinal

effects (i.e. habit-forming propensity or nausea cord, the hypothalamus and the limbic system.

and vomiting) [24].

They have also been identified on peripheral

sensory nerve fibres and their terminals and on

2.1.3. Opioid receptors

immune cells [36]. Each receptor type is associ-

ated with specific functional effects, as shown

Pharmacologic studies performed in the 1970s in Table 2. The best-studied receptor type is the

had suggested the existence of three types of clas- mu receptor (also known as the μ, MOP or OP3

sic opioid receptor, termed mu, delta and kappa receptor), which is found in both spinal and su-

[68], and this was subsequently confirmed by praspinal structures as well as in the periphery.

receptor-cloning studies. Opioid receptors be- It plays an important role in nociception, as well

long to the large family of receptors possessing as respiration, cardiovascular function, intestinal

seven transmembrane domains of amino acids transit, feeding, learning and memory, locomotor

and are coupled to guanine nucleotide-binding activity, thermoregulation, hormone secretion,

proteins known as G-proteins [17]. They reduce and immune functions [25]. Kappa receptors

the intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (also known as κ, KOP or OP2 receptors) have

(cAMP) content by inhibiting adenylate cyclase been implicated in the regulation of nociception,

and also exert effects on ion channels through diuresis, feeding and neuroendocrine secretion.

a direct G-protein coupling to the channel [85]. In addition, as kappa receptor agonists can pro-

The main effects of opioids at the membrane duce dysphoria in humans [25], they appear to

level are thus the promotion of the opening of play a role in regulation of mood. The olfactory

potassium channels and inhibition of the opening bulb, neocortex, caudate putamen and nucleus

of voltage-gated calcium channels [85]. These accumbens contain the highest densities of delta

membrane effects reduce neuronal excitability (δ, DOP or OP1) receptors, with lower densities

as the increased potassium conductance causes in the thalamus, hypothalamus and brainstem

hyperpolarisation of the membrane and reduces [25]. A fourth opioid receptor has been discov-

transmitter release due to inhibition of calcium ered more recently, the NOP receptor (formerly

entry [85]. The overall effect is inhibitory at the referred to as opiate receptor-like 1 [ORL1],

cellular level [85]. However, opioids do increase LC132 or OP4). Pharmacologically this is not a

activity in some neuronal pathways by suppress- classical opioid receptor, as non-selective opioid

ing the firing of inhibitory interneurones [85].

antagonists (e.g., naloxone) display negligible af-

High densities of opioid receptors are present finity; the International Union of Basic and Clini-

in five areas of the central nervous system (CNS): cal Pharmacology (IUPHAR) database of recep-

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

Table 3: Selectivity of opioid drugs and peptides for the three main opioid receptors [85]

mu (μ, MOP or OP3)

delta (δ, DOP or OP2)

kappa (κ, KOP or OP1)

Endogenous peptides

Morphine, codeine,

Etorphine, bremazocine

Fentanyl, sufentanil

Partial/mixed agonists

+: agonist activity; (): partial agonist activity; x: antagonist activity; −: weak or no activity

tors proposes that the NOP receptor is considered way [13]. The classification of opioid drugs and

as a non-opioid branch of the opioid receptor endogenous peptides in terms of their agonist,

family [27].

partial agonist or antagonist activity and their

selectivity for the three main opioid receptors is

2.1.4. Agonists and antagonists

shown in Table 3.

The overall effect of an opioid depends on

2.1.5. Endogenous opioids

its activity at each of the opioid receptors; some

opioids act as agonists on one type of receptor

The search for endogenous compounds that

and antagonists or partial agonists at another. Ag- mimicked the actions of morphine in the 1970s

onist potency depends on two parameters: i) the led to the discovery of the endogenous opioids

affinity of the agonist for the receptor, that is, its [43]. Four classes of endogenous opioids have

tendency to bind to the receptor; and ii) the effi- now been identified: endorphins, enkephalins,

cacy (commonly indicated as intrinsic activity) of dynorphins and endomorphins [56]. Endogenous

the agonist, that is, its ability to initiate changes opioids function as neuromodulators to influ-

which lead to effects once bound. Full agonists ence the actions of other neurotransmitters such

(which can produce maximal effects) have high as dopamine or glutamate [94]. The endogenous

efficacy whereas partial agonists (which can pro- opioid system has been found to be important in

duce only submaximal effects) have intermedi- the modulation of pain, mood, blood-pressure

ate efficacy [87]. The relationship of a drug with regulation and other cardiovascular functions,

its receptor is often likened to that of the fit of a control of respiration, appetite, thirst and sexual

key into its lock – the drug represents the key and activity [94]. There are high concentrations of re-

the receptor represents the lock (Figure 1). Hor- ceptors for endorphins and enkephalins in many

mones, neurotransmitters, drugs or intracellular areas of the CNS, particularly in the periaqueduc-

messengers may all interact with receptors in this tal grey matter of the midbrain, in the limbic sys-

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

Table 4: Clinical features of opioid intoxication and

Drowsiness, stupor or coma

Symmetric, pinpoint, reactive pupils

Decreased peristalsis

Skin cool and moist

Hypoventilation (respiratory slowing, irregular

breathing, apnea)

Reversal with naloxone

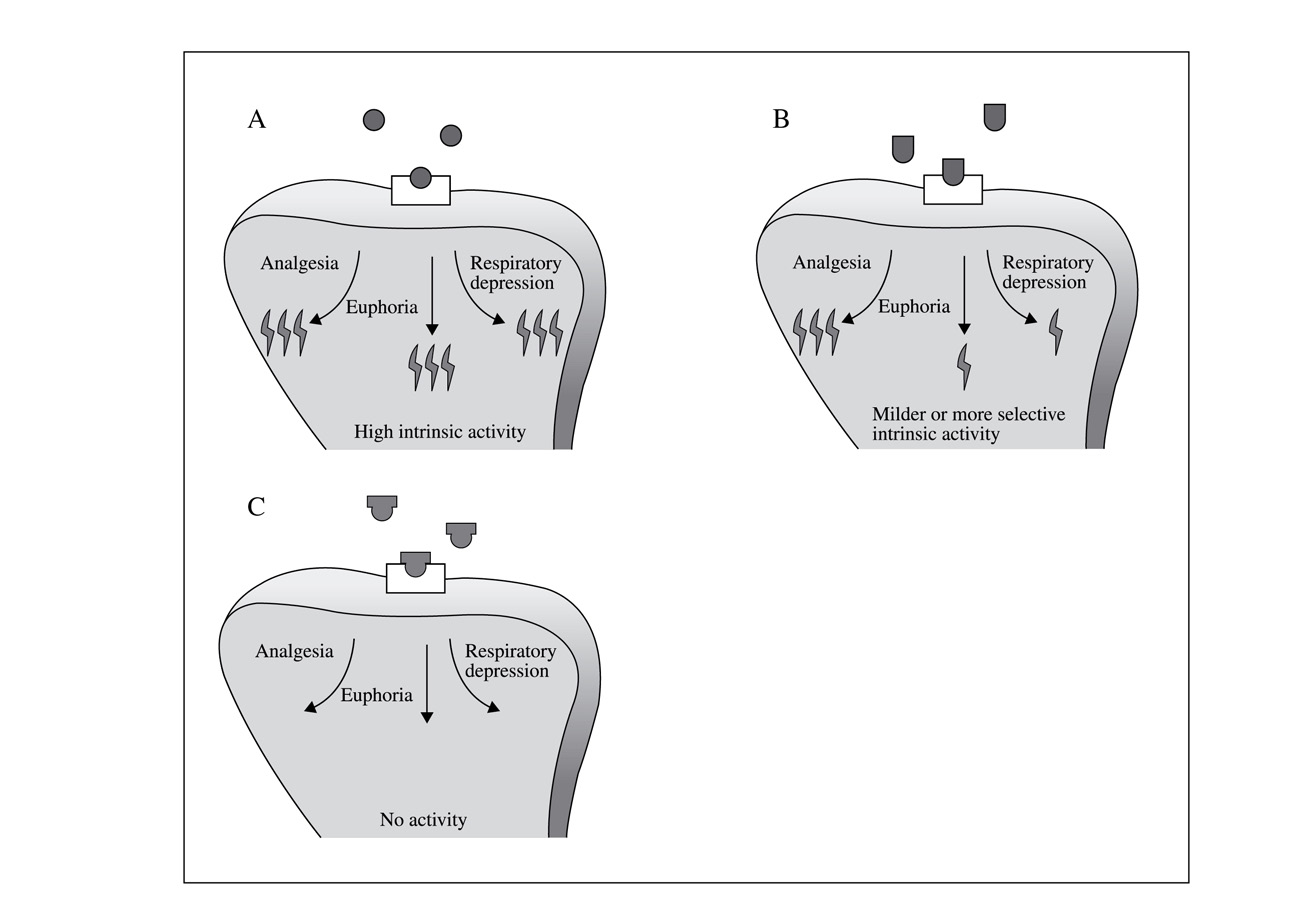

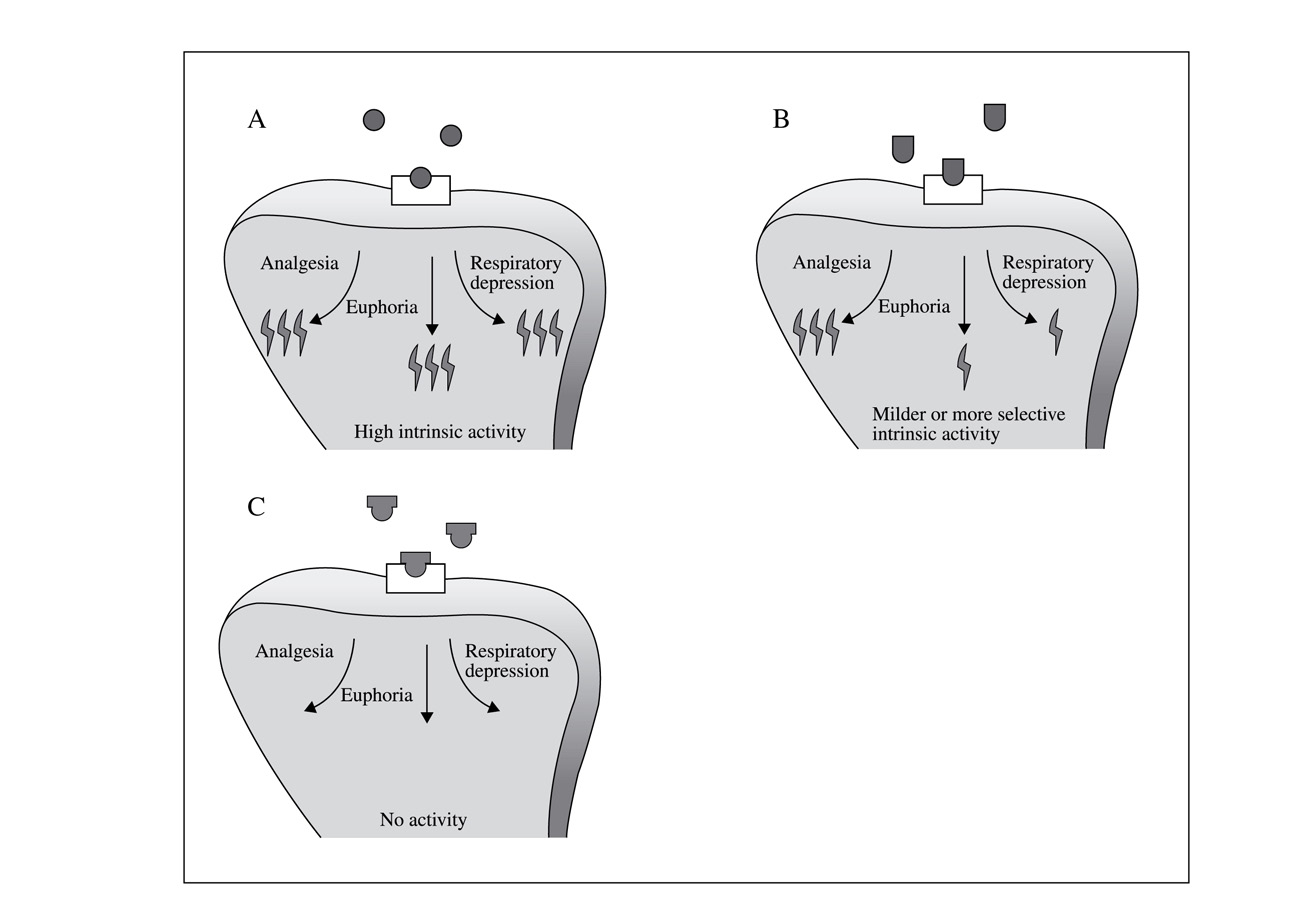

Figure 1: Action of opioid agonists, antagonists

Anxiety, restlessness

and partial agonists. A: Opioid agonist; B: Opioid

partial agonists; C: Opioid antagonists

Chills, hot flushes

tem and at interneurones in the dorsal horn areas.

Myalgias, arthralgias

These areas are involved in pain transmission

or perception and the endogenous opioids are

Abdominal cramping

Vomiting, diarrhoea

thought to be the body's natural pain-relieving

chemicals, which act by enhancing inhibitory ef-

fects at opioid receptors. Opioid drugs elicit their

Tachycardia, hypertension (mild)

effects by mimicking the actions of the endog-

Hyperthermia (mild), diaphoresis, lacrimation,

enous opioids on opioid receptors [13].

Spontaneous ejaculation

2.2. Chronic opioid use: tolerance, physical de-

pendence and addiction

for effects such as constipation and miosis [85].

When the drug is stopped or when its effect

2.2.1. Effects of chronic opioid exposure

is counteracted by a specific antagonist [80], un-

pleasant physical effects occur, which indicates

Although possessing valuable properties (e.g., the occurrence of the withdrawal (abstinence)

analgesia), repeated and chronic exposure to syndrome. Withdrawal symptoms generally rep-

opioids can lead to development of tolerance and resent physiologic actions opposite to the acute

physical dependence. The rate of development of actions of opioid drugs. For example, pupillary

tolerance varies from one opioid to another.

constriction and constipation occur with opiate

Tolerance describes the need to progressive- use, whereas pupillary dilatation and diarrhoea

ly increase the drug dose to produce the effect occur in the withdrawal state [54]. The most

originally achieved with smaller doses, following common symptoms of opioid intoxication and

repeated exposure to opioid agonists. It may de- withdrawal are shown in Table 4. Individuals

velop at different rates for the different effects of who abruptly stop taking morphine are extremely

opioids and can occur over days, weeks or years restless and distressed and have a strong crav-

[90]. Tolerance develops to the analgesic and ing for the drug. Although not life-threatening,

euphoric effects of opioids, and to some of the opioid withdrawal is associated with severe psy-

adverse effects such as respiratory depression, chological and moderate physical distress [54].

nausea and sedation, but does not fully develop The onset of withdrawal symptoms typically

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

Figure 2: Experience of the opioid-dependent individual depending on opioid

concentrations in the body. Reproduced with permission from Newman et al.,

1995 [78]

occurs 8–16 hours after cessation of the use of diction, and it is also referred to as ‘psychological

heroin or morphine, with autonomic symptoms dependence' [86].

appearing first. By 36 hours, severe restlessness,

piloerection, lacrimation, abdominal cramps and 2.2.2. Criteria for opioid dependence/addiction

diarrhoea become apparent. Symptoms reach

their peak intensity at 48–72 hours and resolve

The key criteria indicating that an individual

over 7–10 days [54]. However, negative mood is addicted is when they no longer have control

states and craving may persist for up to 2 years over their drug use and demonstrate a persistent

after abstinence [37, 69]. Symptoms experienced change in reward-seeking behaviour, with an irre-

by the opioid-dependent patient depend on the sistible desire to repeat the drug experience or to

concentration of opioids in their body and their avoid the discontent of not having it. Such an in-

own individual levels of tolerance: the patient stinctive drive is contrary to the person's declared

will experience euphoria when the concentration intentions and underlies relapsing behaviour (re-

of opioids in the body exceeds the tolerance level cidivism). It is the key aspect of addiction, and

and will experience withdrawal symptoms when is also referred to as ‘psychological dependence'

the concentration of opioids in the body is below [86]. A joint statement by the World Health Or-

the dependence level. When the opioid concen- ganization (WHO), the United Nations Office on

tration is in between these two levels the opioid- Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) and the Joint United

dependent patient will look and feel normal (Fig- Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

ure 2) [78]. Evidence of tolerance/withdrawal is defines the key elements of opioid dependence as

termed ‘physical dependence', although it is not a follows: a strong desire or sense of compulsion

constant or exclusive feature of addiction. Addic- to take opioids; difficulties in controlling opioid-

tion manifests with a persistent change in reward- taking behaviour; a withdrawal state when opioid

seeking behaviour, with an irresistible desire to use has ceased or been reduced; evidence of tol-

repeat the drug experience or to avoid the discon- erance, such that increased doses are required to

tent of not having it. Such an instinctual drive is achieve effects originally produced by lower dos-

contrary to the person's declared intentions and es; progressive neglect of alternative pleasures or

underlies recidivism. It is the key aspect of ad- interests; and persistence with opioid use despite

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

clear evidence of overtly harmful consequences bile organisms [35]. Drugs of abuse mediate their

acute reinforcing effects by enhancing dopamine

activity in this neural network, which consists

2.2.3. Neurobiology of opioid- and drug-addiction

of dopamine projections from cell bodies in the

ventral tegmental area to limbic structures and

Advances in knowledge of the neurobiological cortical areas of the brain [35]. It has been pro-

processes that occur following acute and chronic posed that a network of four circuits within the

opioid administration have helped to improve sci- mesolimbic system are involved in drug abuse

entific understanding of how drug addiction de- and addiction: the nucleus accumbens and the

velops, including the role of the specific neuronal ventral pallidum, which are associated with re-

circuits in mediating the reinforcing effects of ward; the orbitofrontal cortex and the subcallosal

opioids and the development of uncontrolled use cortex, which are associated with motivation/

drive; the amygdala and the hippocampus, which

are associated with memory and learning; and the

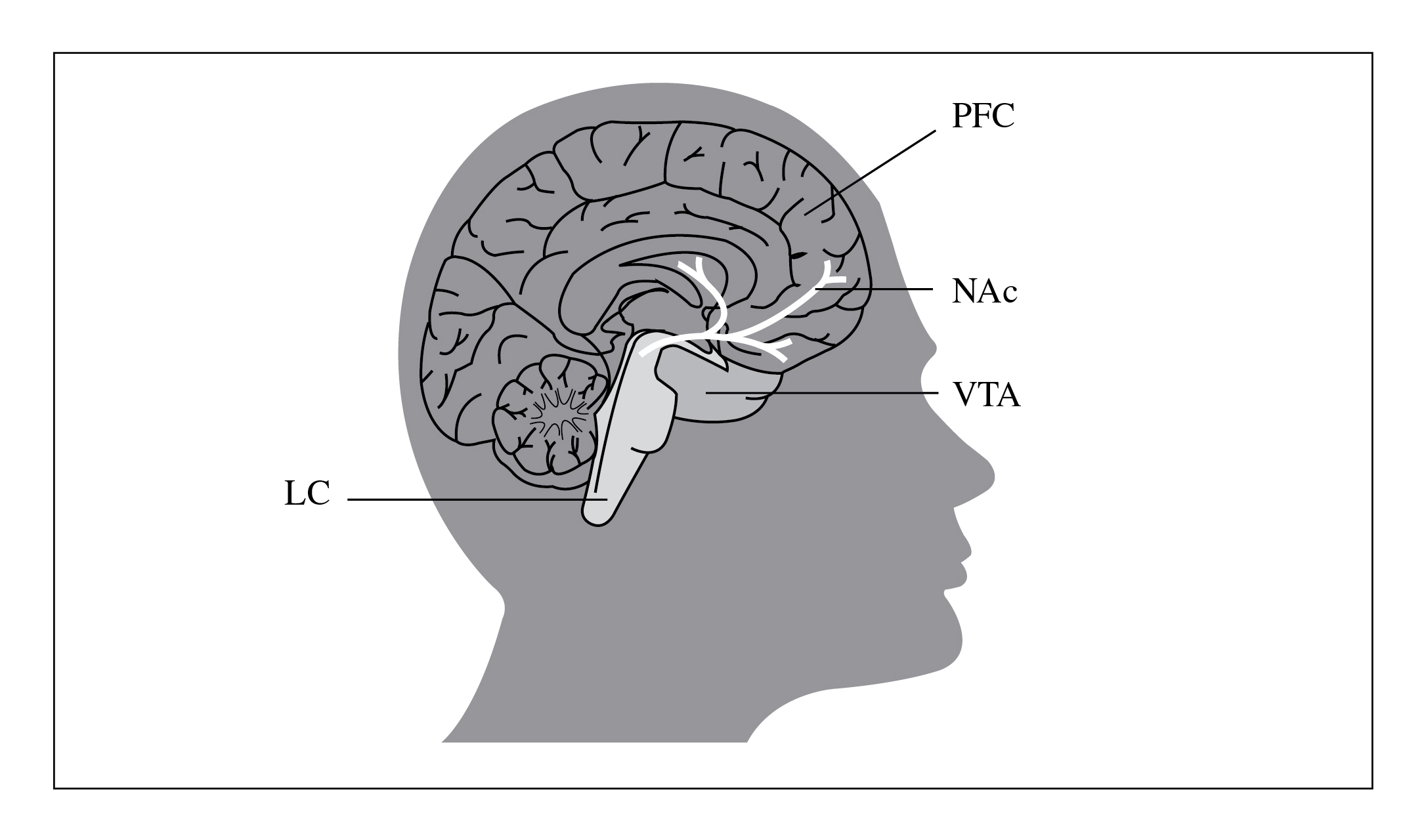

2.2.3.1. The reward pathway

prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate gyrus,

which are associated with control [101]. These

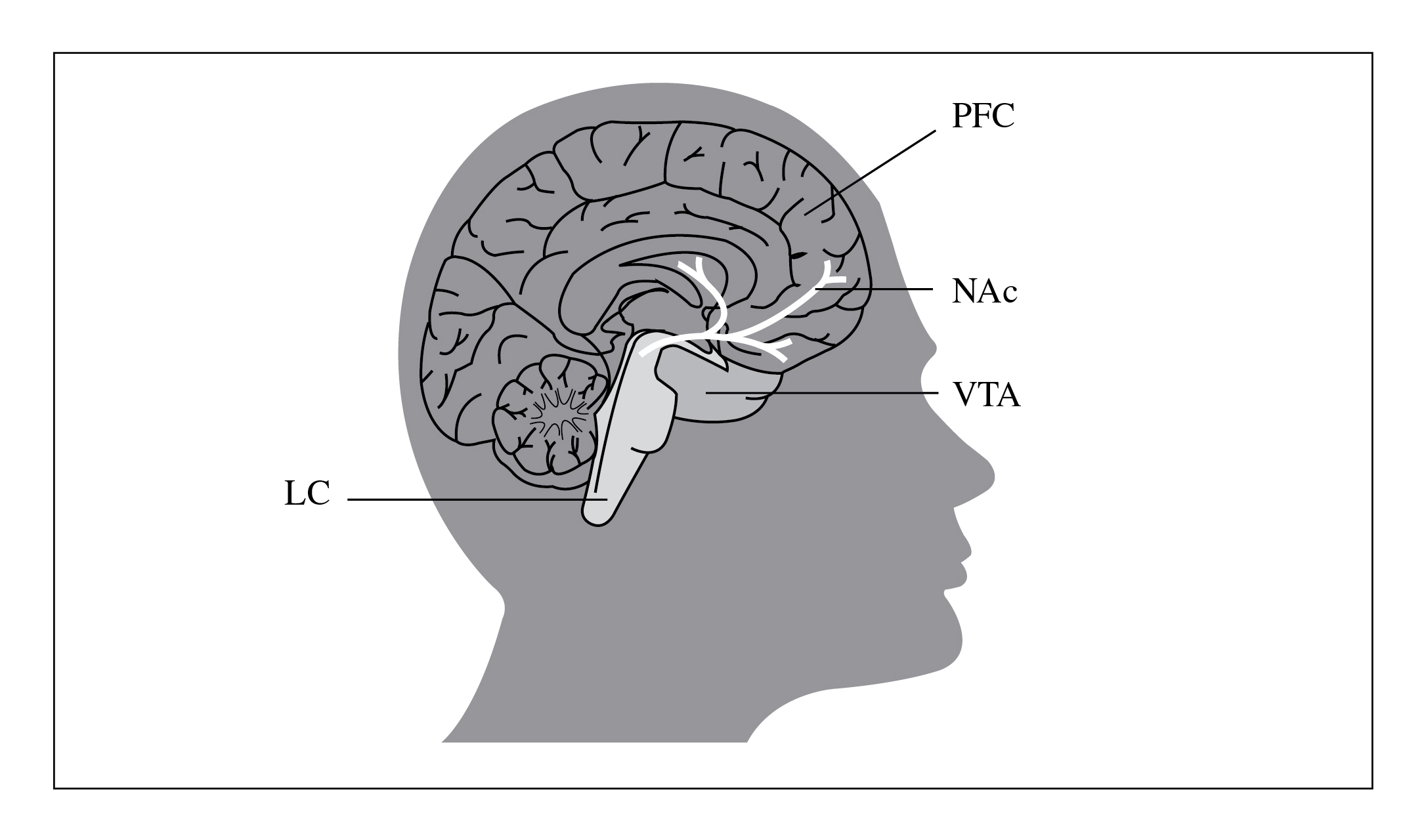

Increased dopamine activity in the mesocorti- four circuits receive direct innervations from

colimbic system (Figure 3) is intimately involved dopamine neurones but are also connected with

in eliciting and reinforcing responses to natural one another through direct or indirect projections

stimuli (e.g., food, drink and sex), which is impor- (mostly glutamatergic), confirming observations

tant to drive behaviour necessary for survival and from preclinical studies indicating that modifica-

reproduction [55]. From an evolutionary point of tions in glutamatergic projections mediate many

view, the capacity to seek rewards as goals is es- of the adaptations observed with addiction [101].

sential for the survival and reproduction of mo- As may be expected from such a complex system,

Figure 3: The mesolimbic reward system. Reproduced with permission from Kosten and George, 2002 [57]

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

other brain regions are thought to be involved in [100]. For excellent reviews of the neurobiology

these circuits (e.g., the thalamus and insula), one underpinning addiction, see Felkenstein, 2008

region may participate in more than one circuit and Volkow, 2003 [35, 101].

(e.g., the cingulate gyrus plays a role in both con-

trol and motivation/drive circuits) and other brain 2.2.4. Relapse

regions (e.g., the cerebellum) and circuits (e.g.,

attention and emotion circuits) are likely to be

A defining feature of drug dependence is the

affected in drug addiction [101]. In the case of incidence of relapse to drug-seeking and drug-

addiction to opioids it is predominantly the inter- taking behaviours following months or years of

action of opioids with mu receptors in the meso- abstinence [116]. It has been estimated that be-

corticolimbic system that appears to mediate the tween 40 and 60% of drug-addicted patients will

behavioural and reinforcing properties [35].

relapse within a year [72] even though they may

have achieved abstinence temporarily alone or

2.2.3.2. Uncontrolled use and craving

through detoxification or environmental interven-

tions. Such a pattern is common to most chronic

Tolerance may develop with repeated opioid relapsing disorders, such as diabetes or hyperten-

use to the extent that the user no longer experi- sion. The relapsing course illustrates the chronic

ences the euphoric effects once achieved with the nature of opioid addiction and the need for long-

drug, despite ingesting higher and higher doses of term approaches to treatment. An important focus

opioids [31]. Chronic opioid users will typically of addiction research has been to identify the be-

continue to exhibit a strong drive to engage in havioural, environmental and neural mechanisms

further drug-seeking and -using behaviours de- underlying drug relapse. Three types of trigger

spite developing tolerance to the euphoric effects have been identified to cause craving and relapse

of opioids. It has been postulated that repeated following extended periods of abstinence: a small

exposure to drugs of abuse disrupts the function ‘priming' dose of the drug; cues previously asso-

of the striato-thalamo-orbitofrontal circuit. This ciated with drug use (e.g., people, places, things,

dysfunction leads to a conditioned response when moods); and stress (e.g., stressful life events as

the addicted subject is exposed to the drug and/or well as anger, anxiety and depression) [114]. As

drug-related stimuli that activates the circuit and opioid-using individuals invariably relapse fol-

results in the intense drive to get the drug (con- lowing opioid withdrawal, detoxification alone

sciously perceived as craving) and uncontrolled does not constitute an adequate intervention for

self-administration of the drug (consciously per- substance dependence; maintenance treatment is

ceived as loss of control). This model of addic- a more effective option for opioid-addicted in-

tion postulates that the drug-induced perception dividuals to resume a normal life and achieve a

of pleasure is particularly important for the initial favourable outcome [78]. Detoxification is, how-

stage of drug self-administration but that with ever, a first step for many forms of shorter- or

chronic administration, pleasure alone cannot longer-term abstinence-based approaches, i.e.,

account for the compulsive drug intake. Rather, those in which no opioid agonist pharmacother-

dysfunction of the striato-thalamo-orbitofrontal apy is used. Both detoxification with subse-

circuit, which is known to be involved in pers- quent abstinence-oriented treatment and agonist

erverative behaviours, accounts for the compul- maintenance treatment are considered essential

sive intake [100]. During withdrawal and without components of an effective treatment system for

drug stimulation, the striato-thalamo-orbitofron- people with opioid dependence [113]. Overcom-

tal circuit becomes hypofunctional, resulting in ing opioid dependence is not easy: at the cellular

a decreased drive for goal-motivated behaviours level, the pathological changes that occur as a re-

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

sult of drug use can persist even after drug use lapse and results from enduring cellular changes.

has ceased [45, 51] and the likelihood of relapse Changes in protein content and/or function often

actually increases during a period of abstinence become greater with increasing periods of with-

(a process called ‘incubation') as a result of the drawal, which is consistent with the possibility

neuroadaptations that occur in drug dependence that the more temporary changes in protein ex-

[40, 93]. Pharmacotherapies should ideally be ac- pression that mediate the transition to addiction

companied with motivation, social support, and may induce changes in protein expression that

positive coping strategies to fully achieve reha- convert vulnerability to relapse from a temporary

bilitative goals [61].

and reversible phase into permanent features of

addiction [52].

2.2.5. Stages of addiction

2.2.6. Risk factors for opioid dependence

The development of addiction may be consid-

ered to consist of three stages: (1) acute (immedi-

Dependence is not an inevitable consequence

ate) drug effects; (2) transition from recreational of opioid use, as demonstrated by their wide-

use to patterns of use consistent with addiction; spread use as a treatment for chronic pain [79]. It

and (3) end-stage addiction, which is character- has been proposed that addictive disease does not

ised by an overwhelming desire to obtain the drug, begin with the onset of substance use, but that an

a diminished ability to control drug seeking and individual's complex history of risk and protec-

reduced pleasure from biological rewards [52]. tive factors increase or decrease the likelihood of

These stages are associated with neurobiological their developing an addictive disorder when they

adaptations, including a switch from dopamine- use a substance for the first time [12]. A large

to glutamate-based behaviour as different parts number of risk and protective factors have been

of the neural circuitry play the key role [52]. identified, the most important of which is genet-

The first stage of addiction, acute drug effects, is ics, with some research suggesting that between

caused by supraphysiological levels of dopamine 40% and 60% of the vulnerability to addictive

being released throughout the motive circuit disease is accounted for by genetic factors [60].

which induces changes in cell signalling. These However, exposure to certain substances can be

changes lead to short-term neuroplastic changes, sufficient to induce dependence in the absence

persisting for a few hours or days after drug in- of risk factors. Associations have been found

take, which initiate cellular events involved in the between substance abuse and polymorphisms in

process of addiction. The second stage of addic- genes encoding opioid (OPRM1 and OPRK1),

tion, the transition from recreational drug use to serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine-1B [HTR1B]

addiction, is associated with changes in neuronal and melanocortin (MC2R) receptors, endogenous

function that accumulate with repeated drug use opioids (prodynorphin [PDYN]) and neurotrans-

and diminish with drug discontinuation over days mitter enzymes (catechol-O-methyltransferase

or weeks. There are also alterations in the con- [COMT] and tryptophan hydroxylase [TPH])

tent and function of various proteins that are in- [115]. Other factors known to play a role in the

volved in dopamine transmission (e.g., tyrosine development of addictive disorders include an

hydroxylase, dopamine transporters, RGS9-2 and individual's temperament, psychopathology, at-

D2 autoreceptors) that persist for a few days af- titudes and perceptions. Society, including fam-

ter drug discontinuation. However, these changes ily, peer group, school and community, also have

appear to be compensatory and may not directly important implications for the development of

mediate the transition to addiction. End-stage addictive disease [12]. Prevention strategies have

addiction is characterised by vulnerability to re- been demonstrated to play an important part in

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

reducing the risk of opioid dependence among dependence in the same way, treatment success

vulnerable groups [76].

may be defined as a decrease in drug use with

only occasional relapses or abstinence from drug

2.2.7. Opioid dependence as a chronic, relapsing brain use with only occasional relapses rather than total

abstinence. Total abstinence develops gradually,

is rarely achieved soon after initiating treatment,

Individuals who are drug dependent have and depends on ongoing treatment rather than

historically been considered to be ‘bad', ‘weak' being self-maintaining in the absence of chronic

people who are unable to control their behav- treatment.

iour and do not deserve treatment. Among the

Optimal management of opioid dependence

scientific community, however, advances in our requires a multi-faceted approach in order to ad-

understanding of the neurobiology of addiction, dress the neurobiological, social, behavioural and

the pharmacology of opioids and their receptors, psychological aspects of the condition [62]. The

and the discovery that some individuals may be pharmacotherapy of opioid dependence will be

particularly susceptible to drug dependence have discussed in more detail in Part 3 of this supple-

led to greater appreciation of the condition being ment.

a chronic, relapsing brain illness. In addition, the

substantial changes in brain structure and func- 2.3. Conclusion

tion observed in drug dependence that persist

after individuals have stopped drug use provide

An understanding of the mechanisms respon-

further evidence that the condition should be con- sible for opioid addiction is critical for optimal

sidered a medical condition rather than a moral treatment of this chronic brain condition. Im-

weakness. Viewing drug dependence as a chronic provements in our understanding of the cellular

illness akin to diabetes or chronic hypertension processes responsible for opioid dependence,

changes the way in which treatment success is addiction and relapse have helped to inform the

recognised. In the case of diabetes, for example, now widespread view that opioid dependence

complete cure is not currently a feasible outcome is a chronic disease requiring medical treatment

and a decrease in blood glucose would therefore rather than a purely moral or social problem that

be indicative of treatment success. Considering can be ‘cured' by criminal-justice solutions. Ulti-

Key learning points

Opioids are drugs that share some of the pharmacological effects of opium

Opioid receptors are widely distributed in the nervous system

Mu-receptor activation produces direct opioid effects, including euphoria

Opioids promote the release of dopamine in the reward pathway (ventral tegmental area, nu-

cleus accumbens, prefrontal cortex)

Opioids are classified as agonists (complete, partial) or antagonists according to their intrinsic

activity at different receptors

Neuroadaptations that occur in response to chronic opioid lead to:

Tolerance: reduced effect of drug for a given dose

Withdrawal: emergence of withdrawal syndrome upon abstinence or reduced drug levels

Cravings and vulnerability to relapse

Opioid dependence is a chronic, relapsing brain disorder

Relapse is a symptom of the disorder and not a sign of abstinence failure

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

mately, increased understanding of the neurobiol- heterogeneity of the opioid-dependent popula-

ogy of addiction should help to optimise the way tion makes treatment standardisation implausi-

we manage drug-dependent individuals with the ble [108]. A comprehensive, long-term treatment

treatment options we currently have at our dis- plan should be developed based on a multi-facto-

posal and also inform the development of new rial assessment and the best available clinical evi-

dence. All decisions should be made in concert

with principles of medical ethics and considera-

3. Clinical assessment of opioid

tion of patient preferences [111].

3.1. Key components of patient assessment in

Effective management of opioid dependence

includes a comprehensive patient assessment.

The goals of the assessment are to confirm a

A detailed patient assessment should consider

diagnosis of opioid dependence, determine the specific physical, psychological and social fac-

appropriate course of therapy and identify any tors, in addition to past and current drug use, in

co-existing physical or psychosocial conditions order to assess the patient's condition and treat-

that may affect treatment outcomes [108, 111]. ment options (Table 5). Psychological assess-

As the number of options to treat opioid addic- ment of patients is critical as psychosocial fac-

tion increases across a range of clinical settings, tors, including co-existing psychiatric disorders

it becomes possible and desirable to tailor ther- and cognitive impairment, patient readiness and

apy to individual needs [111]. Furthermore, the motivation for treatment, contribute to non-com-

Table 5: Key features of patient assessment [108, 111]

Demographics and family history

Psychiatric history

Past and current drug use

Past treatment experience

Clinical examination

Assessment of intoxication/withdrawal

Presence of opportunistic infection(s)

Presence of co-morbidities

Lab investigation(s)

Urine and plasma drug screen, LFTs, HIV, hepatitis B

Co-existing conditions

Infectious diseases

HIV, hepatitis C and B, sexually-transmitted diseases,

Other substance abuse

Alcohol, benzodiazepines, stimulants, barbiturates,

cocaine, marijuana, hallucinogens

Psychiatric disturbance

Depression, anxiety, personality disorders, cognitive

Living conditions

Extent of integration into drug community,

Legal/criminal issues

Past/present involvement with legal system and

Occupational situation

Current and past employment

Social/cultural factors

Language barriers, education level, religion

Support for treatment and avoidance

Patient motivation

Short-term and long-term goals, and reason for

seeking treatment

LFT: liver function tests; TB: tuberculosis; CBC: complete blood count; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

pliance and treatment failure [108].

it does not distinguish addictive use from thera-

peutic dependence on prescribed drugs. We use

3.2. Diagnosis of opioid dependence

the term dependence here to mean addiction (i.e.,

a persistent change in reward-seeking behaviour,

As of 1964, the World Health Organization with an irresistible desire to repeat the drug ex-

has recommended the term ‘substance addiction' perience or avoid the discontent of not having it,

be replaced by the term ‘substance dependence' which is contrary to the person's declared inten-

[111] (www.who.int). The term ‘substance de- tions). Differentiating between opioid use, abuse

pendence' is somewhat ambiguous, however, as and dependence is critical to establishing the

Table 6: Definitions of substance abuse and dependence [2,109]

Substance abuse (DSM-IV-TR)(2)/Harmful use (ICD-10) (109)

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically A pattern of psychoactive substance use that is causing

significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or damage to physical or mental health; adverse social

more) of the following, occurring at any time in the same

consequences are also common, but not sufficient to

12-month period:

establish a diagnosis of harmful use

Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfil major

role obligations at work, school, or home

Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is

physically hazardous

Recurrent substance-related legal problems

Continued substance use despite persistent or recurrent

social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by

the effects of the substance

In addition, the individual must never have met the criteria

for substance dependence for the substance in question

A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically A cluster of physiological, behavioural, and cognitive

significant impairment or distress. Three (or more) of the

phenomena in which the use of a substance or a class of

following, occurring at any time in the same 12-month

substances takes on a much higher priority for a given

individual than other behaviours that once had greater

value. Three or more of the following have been present

together at some time during the previous year:

Taking the substance in larger amounts or over a longer

Strong desire or compulsion to take the substance

period than was intended

Difficulty controlling substance use (onset, termination,

Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or

or levels of use)

control substance use

A physiological withdrawal state when substance use is

Spending a great deal of time in activities necessary to

stopped or reduced

obtain, use, or recover from the substance

Evidence of tolerance (increased doses are required in

Giving up or reducing important social, occupational, or

order to achieve the effects originally produced by lower

recreational activities because of substance use

Continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or Progressive neglect of alternative pleasures or interests

recurrent physical or psychological problem likely to have because of time spent to obtain, use, or recover from the

been caused or exacerbated by the substance

Persisting with substance use despite clear evidence of

overtly harmful consequences

DSM-IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision;

ICD, International Classification of Diseases

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

most effective course of treatment, if any. A diag- often a temporary stage of opioid usage; depend-

nosis of any opioid disorder is made using criteria ence develops rapidly as a result of the powerful

similar to other substance abuse disorders [108]. reinforcing qualities of the opioid and the emer-

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental gence of tolerance [28, 108].

Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-

Notably, the DSM-IV-TR requires criteria for

IV-TR) [2] describes two distinct categories for dependence to be fulfilled within a 12-month pe-

substance-use disorders: abuse and dependence riod, although possibly on different occasions.

In other words, a diagnosis can be based on a

The most important feature that differentiates relatively recent period of physical dependence

substance abuse from dependence is a loss of (e.g., in the past month) evidenced by signs of

control (e.g., persistent or strong desire to take withdrawal and tolerance, as long as features of

the substance, unsuccessful efforts to cut down previous escalating substance use or abuse have

or control substance use, continued usage despite occurred in the same 12-month period. In addi-

knowledge of harmful consequence and neglect tion, even if the pattern of use is not currently

of other activities). It should be noted that toler- problematic, the recurrence of problems within

ance and withdrawal are included in the potential the same 12-month period is (from a diagnostic

criteria for substance dependence in both DSM- perspective) considered equivalent to a constant

IV-TR and ICD definitions but neither tolerance problematic pattern of use. Conceptually, a diag-

nor withdrawal are required to establish the diag- nosis of substance dependence can also be made

nosis of abuse or dependence [2, 109]. Converse- for a past period, although the patient may be un-

ly, the sole presence of tolerance and withdrawal dergoing a remission phase. Therefore, a progno-

in the absence of other criteria, may indicate sis of long-lasting remission in the presence of a

what might be termed a ‘normal', medical sta- retrospective diagnosis of drug addiction is unre-

tus corresponding to habitual, controlled use of alistic.

a tolerance-inducing substance (e.g., nicotine or

alcohol) or therapeutic dependence on a toler- 3.3. Assessing opioid intoxication and withdrawal

ance-inducing prescribed drug (e.g., methadone

or buprenorphine). The DSM-IV-TR requires

The documentation of the signs of opioid in-

the clinician to specify whether the substance toxication or withdrawal is part of establishing a

dependence is with or without physiological de- diagnosis of opioid dependence (Table 7). The de-

pendence (manifested by evidence of tolerance or gree of opioid intoxication or withdrawal should

withdrawal) [2].

be evaluated with the reported time of last use.

A diagnosis of abuse is subordinate to that of

Clinical assessment is complicated by the

dependence: in other words, all dependent pa- fact that opioid users commonly abuse several

tients are also abusers, whereas abusers can be substances including alcohol, benzodiazepines,

assessed as such after ruling out a diagnosis of stimulants, marijuana, cocaine and nicotine,

dependence. Furthermore, patients who do not which may result in additional symptoms such

meet the criteria for abuse may fall into a cate- as tremors, delirium or seizures [1]. Care must

gory of non-pathologic use, comprising irregular be taken to make a differential diagnosis against

or habitual use, with possible features of toler- other conditions that may share similar symp-

ance and dependence. Typically, dependence is toms [108], such as panic attack, gastroenteritis,

the culmination of a pattern of abuse which starts peptic ulcer and pancreatitis.

with occasional, social or recreational drug use or

Injection sites are valuable indicators when

as part of a legitimate medical regimen, such as determining the chronology of drug use [111].

with the treatment of pain [1]. Abuse is, however, The most common sites for injection include

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

Table 7: Signs of opioid intoxication and withdrawal [108, 111]

Signs of opioid intoxication

Signs of opioid withdrawal

Drooping eyelids

Constricted pupils

Muscle aches and abdominal cramps

Reduced respiratory rate

Itching and scratching

Difficulty sleeping

Dry mouth and nose

Vomiting and diarrhoea

Agitation and restlessness

Elevated respiratory rate, blood pressure and pulse

the cubital fossa (area on the inside of the elbow some form of immunoassay, are generally recom-

joint) and the groin although superficial veins in mended before making treatment decisions. Gas–

the extremities and neck are also used [28, 111]. liquid chromatography (GLC) and gas chroma-

Recent injection marks are usually small and red tography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) are very

and are sometimes inflamed or surrounded by sensitive and specific tests, but are labour inten-

slight bruising. Older injection sites are usually sive and expensive and are thus often reserved

not inflamed, but may show pigmentation chang- for confirmation of other forms of testing, such as

es (either lighter or darker) and the skin may have urinalysis [98, 108].

atrophied. A combination of recent and old injec-

Urinalysis is an inexpensive, although not

tion sites would normally be seen in an opioid- sensitive, form of screening for opioids and other

dependent patient with current neuroadaptation. substances of abuse. Interpretation of urinalysis

The visible injection sites should be consistent results requires knowledge of the specific test or

with the reported history [111].

reagents used as well as the pharmacokinetics

of the substance or substances being tested [98,

3.4. Assessment of co-existing conditions

111]. Heroin is metabolised to 6-monoacetylmor-

phine (6-MAM), then to morphine and eventually

Physical and biological assessment of the to codeine. Therefore, the presence of 6-MAM is

patient not only confirms dependence, but also usually specific for recent heroin use. Morphine,

provides important information on their overall with or without small amounts of codeine, can

health, fitness and willingness to undertake treat- indicate either heroin or morphine use in the last

ment. A trusting relationship between clinician few days. However, small amounts of morphine

and patient is valuable to establish the free flow in the presence of large amounts of codeine can

of information. A non-judgemental and affirm- suggest intake of high doses of codeine, as co-

ing approach can help to alleviate the sense of deine is also metabolised to morphine [111].

shame and diminished self-esteem many patients

A positive urine test for opioids must be

feel that often leads to the withholding of critical judged cautiously. Although patients are usually

information [38, 111]

required to test positive for opioids in order to

Although important, self-reporting by pa- be offered treatment, the presence of opioids in-

tients often results in questionable validity and dicates recent use, but not necessarily abuse or

reliability [111]. As a result, drug screens, using dependence [111]. On the other hand, the absence

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

of opioid does not exclude either abuse or addic- 3.5. Psychiatric co-morbidities

tion, but merely indicates that the individual has

not used opioids in the previous week. Converse-

In addition to physiological symptoms, as-

ly, positive findings are possible after ingestion of sessment of a patient's behaviour, psychology

large amounts of poppy seeds [111] or for people and cognitive functioning is important in the di-

exposed to prescribed opioids. Urinalysis results agnosis of opioid dependence. Psychological as-

should therefore always be used in the context of sessment includes determining the presence of

a more comprehensive patient assessment to con- co-existing psychological conditions, cognitive

firm a diagnosis of opioid dependence.

impairment, and consideration of the patient's

Further serum testing can detect the presence motivation to treatment and short- and long-term

of other substances of abuse (e.g., alcohol), HIV, goals.

hepatitis C and other common infectious diseases.

Several large-scale epidemiologic studies in-

Voluntary testing for HIV and hepatitis C should dicate approximately 50% of patients with drug

be offered as part of an individual assessment, or alcohol dependency also have psychiatric

with counselling offered before and after the test. distress [82]. Mood and anxiety disorders are

In particular, HIV testing should be routinely of- common in the opioid-dependent population, in

fered to patients in areas with high HIV incidence addition to antisocial behaviour and other per-

rates, particularly if they fall into multiple risk sonality disorders, all of which affect treatment

Table 8. Examples of standardised questionnaires for patient assessment [6,48]

Severity of Opioid Dependence Questionnaire (SODQ) Physical aspects of opioid dependence

Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire

Physical aspects of alcohol dependence

The Symptom Check List (SCL-90) and General Health Global assessment of mental health

Questionnaire (GHQ)

The Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Substance-induced major depression

Mental Disorders (PRISM)

categories. Research suggests opioid-dependent choices and outcomes [33]. It has been estimated

HIV patients have decreased access to quality that up to 16% of opioid dependents suffer from

HIV care and medication, and are more likely to major depression, which is more commonly as-

be non-compliant with treatment [111]. Serology sociated with poly-drug use. Chronic, episodic

testing and vaccination for hepatitis B is recom- low-grade depression or dysthymia can progress

mended for all patients. To offset the risk of pa- to full-blown depression as a result of the stress

tients neglecting to return for repeated treatments and trauma associated with opioid dependence

to complete a hepatitis B vaccination program, [28, 82]. Acute mood disturbances (depressed

vaccination could commence before serology mood, anxiety) are also apparent during opioid

testing, and accelerated vaccination schedules withdrawal [46]. Consequently, when assessing

should be considered [111]. As part of a complete patients, it is important for clinicians to establish

assessment, screening for tuberculosis and sexu- any pre-existing psychological conditions and

ally transmitted diseases should also be consid- recognise that the short- and long-term effects of

ered [38, 111]. A pregnancy test for women with opioids, their withdrawal symptoms and the trau-

reproductive potential should be offered, as early ma of addiction, can all produce symptoms that

as possible in the course of treatment [108, 111]. are similar to those that characterise many mental

disorders [82]. Nevertheless, clinicians should be

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

aware of unusual opioid-related symptoms, such the results should be interpreted in combination

as psychosis or mania, which may require acute with a complete clinical assessment.

The tools for gathering social and cultural in-

The presence of psychiatric conditions also has formation are not as well developed or widely

important implications for treatment choices and available as for physical assessment. Although

medication management. Pharmaceutical agents there is a lack of assessment tools, available re-

such as methadone and buprenorphine have been search suggests that social assessment, e.g., pa-

shown to have a beneficial effect on mental disor- tients' living conditions, occupational situation

ders as well as addiction [82].

and legal issues, needs to be an on-going process,

beyond the scope of a single interview [108].

3.6. Patient assessment tools

Several instruments and questionnaires have

been developed to assist in the patient assessment

A diagnosis of opioid dependence is contin-

process when substance abuse is suspected (Ta- gent on an individualised, comprehensive patient

ble 8). Standard questionnaires can be a useful assessment, which considers the particular risks

adjunct to the assessment process, provided they of this patient population. When considered col-

are delivered in the context of a relaxed patient lectively, the information gained from a complete

interview [48]. The use of structured and semi- physical and psychosocial examination and his-

structured interviews and standardised assess- tory will help to differentiate between substance

ment tools has also improved the reliability of co- use, abuse or dependence, and identify the best

morbid psychiatric diagnoses [82]. In every case, course of treatment.

Key learning points

A comprehensive and individualised patient assessment is critical for the diagnosis of

opioid dependence

The key components for a comprehensive patient assessment include:

Physical/biological evaluation and patient history – drug use, abuse and dependence,

Co-existing somatic and psychiatric conditions

Psychological/social functioning

The potential for tolerance and withdrawal is common to non-pathologic (controlled) use,

abuse and dependence, but is not required to diagnose drug dependence

Documentation of opioid intoxication or withdrawal is important in diagnosis, and should

be made in the context of reported time of last drug usage

Examination of new and old injection sites aids the determination of drug-use chronology

Serum and urine testing is recommended to detect opioids and substances of abuse, as well

as co-existing infectious diseases and conditions

A thorough psychiatric assessment is recommended to detect mental symptoms and to

identify psychiatric co-morbidities, which affect a substantial proportion of the opioid-de-

pendent population

Numerous standardised assessment tools and questionnaires are available to assess de-

pendence, physical and mental health

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

In addition to confirming the presence or ab- practices [111]. Harms to society associated with

sence of opioids and other substances of abuse, opioid dependence include criminal activity and

clinicians should ensure the necessary serum and the economic burden associated with healthcare

urine testing is undertaken to detect co-existing costs (treatment and prevention services, costs

conditions that may affect treatment. Importantly, incurred due to additional health problems), so-

the patient's psychological health must be con- cial welfare and criminal-justice services [111].

sidered, given the high incidence of psychiatric The objectives of treatment for opioid-dependent

co-morbidity and the implications for treatment patients are, therefore, to: reduce dependence on

choice and outcome. A number of standardised abused drugs; reduce the morbidity and mortality

patient assessment tools may aid in the assess- caused by the use of opioids of abuse, or associat-

ment and diagnostic process.

ed with their use, such as infectious diseases; im-

As with other chronic conditions, treatment prove physical and psychological health; reduce

should be structured in such a way as to provide criminal behaviour; facilitate reintegration into

long-term support to patients. Assessment of the the workforce and education system and improve

patient's response to therapy should be undertak- social functioning [113]. Achieving these objec-

en on a regular basis, with a continued focus on tives has clear medical, economic and social ben-

outcome-oriented and individualised treatment.

efits [113]. Accordingly, the World Health Organ-

ization (WHO) has included the opioid agonists

4. Maintenance pharmacotherapies:

methadone and buprenorphine on their model list

treatment principles and clinical

of essential medicines as a result of their strong

evidence base [112]. Essential medicines are de-

fined as those that satisfy the priority healthcare

This section outlines the main principles, needs of the population and they are selected with

goals and strategies underlying medically as- due regard to public-health relevance, evidence

sisted approaches to opioid-dependence treat- on efficacy and safety and comparative cost-ef-

ment, the unique pharmacological profiles of the fectiveness [112]. Access to essential medicines

therapies available to treat opioid dependence, is considered a fulfilment of the human right to

and the safety and efficacy considerations that health according to international law [42].

are relevant to the use of these pharmacological

interventions throughout the different stages of 4.1.2. Elements of drug-dependence treatment

Treatment of opioid dependence must address

4.1. Principles, goals and strategies for treating the multiple needs of the patient. Pharmacologi-

cal treatments (which are discussed in detail here)

are the critical component of the treatment proc-

4.1.1. Overal aims of drug-dependence treatment

ess but behavioural interventions and/or coun-

selling therapies to address underlying mental

Opioid dependence is a chronic and relaps- disorders and impaired psychosocial functioning

ing medical disorder [62] with consequences also play a key role [77]. Comprehensive pro-

that primarily affect the individual but also have grammes, involving access to psychosocial and

broader effects. Harms to the individual include counselling services and referral to vocational,

an increased risk of mortality as a result of over- financial, housing and family assistance, can help

doses, violence, suicide and smoking- and alco- address the broader aspects of addiction. Indeed,

hol-related diseases; and an increased risk of HIV combining pharmacological treatments with

and hepatitis C infection through unsafe injection counselling aimed at promoting treatment adher-

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

ence and lifestyle change can greatly enhance the is defined as the administration of thoroughly

effectiveness of treatment [92]. Pharmacological evaluated opioid agonists, by accredited profes-

maintenance treatment also helps to initiate and sionals, in the framework of recognised medical

retain contact between patients and substance- practice, to people with opioid dependence, for

abuse specialists, thus enabling these other inter- achieving defined treatment aims [110]. The pri-

ventions to be delivered.

mary aims of maintenance pharmacotherapy are

Due to the complexity of drug dependence, to reduce drug craving and illicit opioid use, and

one treatment approach is not appropriate for eve- where necessary, to prevent withdrawal symp-

ry patient. Pharmacological interventions such toms. By reducing the drive to engage in contin-

as opioid agonist treatments should be initiated ual addictive-drug-seeking and -using behaviour,

according to evidence-based quality standards maintenance treatment can provide an opportu-

to ensure safety and efficacy. Over time, the ap- nity to address the broader ramifications of each

propriate dose and other aspects of treatment can individual's dependence-related problems (e.g.,

be individualised to the patient's needs, without impaired psychosocial functioning and physical

losing the critical factors of success. Treatment health), reduce associated risks (e.g., overdose

plans must be continually assessed and modified mortality, infectious-disease transmission), and

to ensure they meet the patient's changing needs minimise the socio-economic burden imposed on

wider society (e.g., criminality, lost productivity,

healthcare costs of untreated opioid dependence).

4.1.3. Overview of treatment pathways

The medications most frequently used as mainte-

nance therapies are the opioid agonists methadone

The primary pharmacological approach to (typically administered as an oral syrup) and bu-

treating heroin dependence involves opioid ago- prenorphine (administered as a sublingual tablet).

nist maintenance treatment – also known as medi- Buprenorphine is available in two formulations: a

cally assisted treatment, and less appropriately as monotherapy and a buprenorphine–naloxone (4:1

opioid replacement therapy or opioid substitution ratio) combination product designed to reduce the

therapy. Opioid agonist maintenance treatment potential for misuse and diversion. Additional op-

drug to an opioid

agonist for long-

Medically supervised withdrawal

Slow reduction of agonist dose until the

The patient remains on a consistent

patient is completely drug free; typically in

agonist dose level that allows him/her

association with psychosocial support

to function properly

Figure 4. Phases of heroin dependence treatment

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

tions that are used less frequently and have been tion alone cannot be regarded as a viable treat-

less thoroughly evaluated include slow-release ment approach for drug dependence. Rather than

oral morphine and injectable therapies including a first step into long-term treatment, it has been

injectable methadone and diamorphine. The main likened to a ‘revolving door'; many individuals

phases of maintenance treatment are summarised who begin detoxification do not complete it and

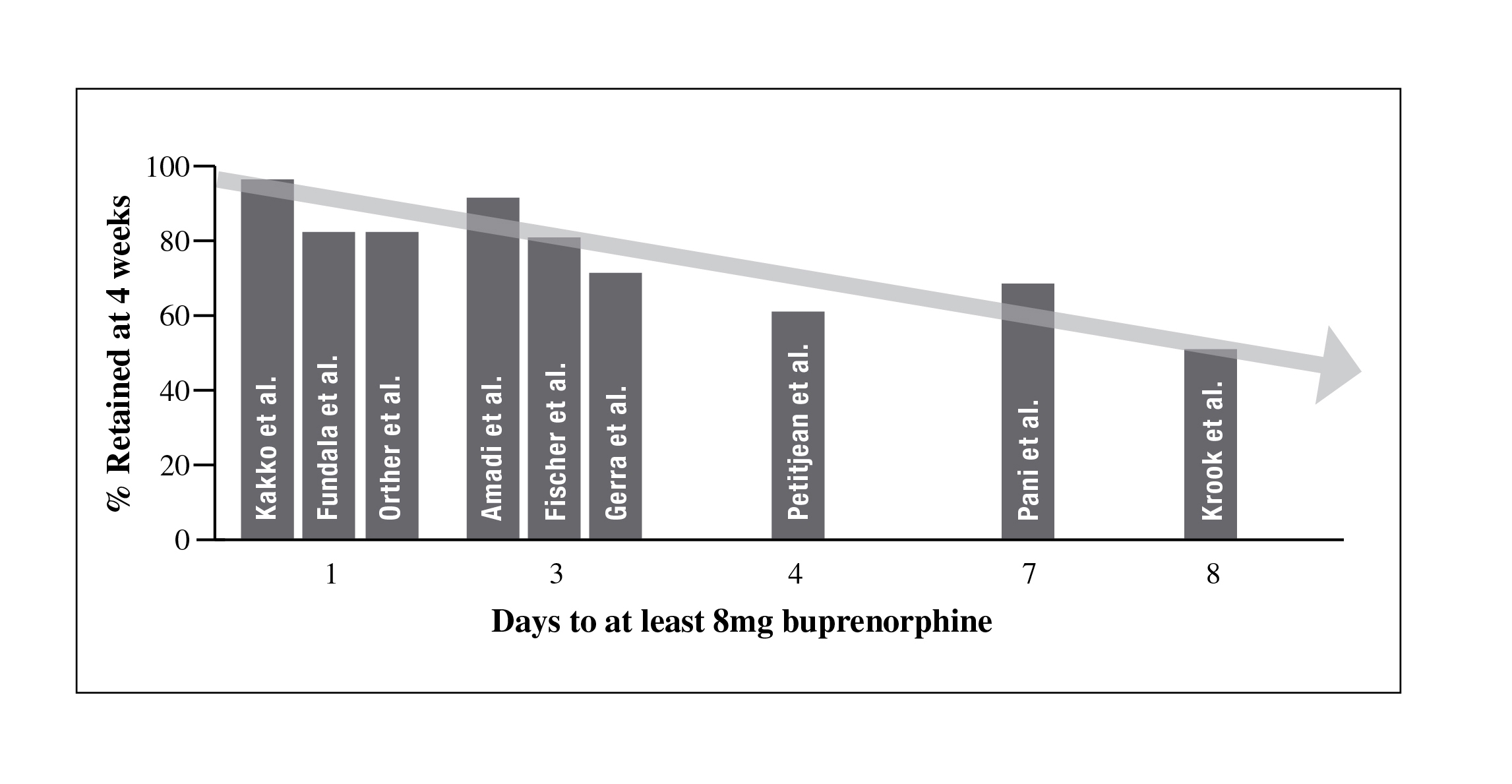

in Figure 4. Following induction and stabilisa- many individuals who complete detoxification do

tion, patients typically need to be maintained on not go on to more definitive treatment [70]. Re-

opioid agonist therapy for at least 12 months in sults from a placebo-controlled, randomised trial

order to achieve enduring positive treatment out- of buprenorphine maintenance versus a tapered

comes [41]. Opioid maintenance treatment is as- 6-day regimen of buprenorphine subsequently

sociated with a substantial reduction in the use followed by placebo (individuals in both arms re-

of heroin and other illicit opioids, crime and the ceived cognitive behavioural therapy to prevent

risk of death through overdose. A WHO posi- relapse plus weekly counselling), demonstrated

tion paper on maintenance treatment states it to that buprenorphine maintenance was far superior

be an effective, safe and cost-effective modality to detoxification (1-year retention rates of 75%

for the management of opioid dependence [113]. vs 0% and negative urine screens for illicit opi-

Compared to detoxification or no treatment, both ates, central stimulants, cannabinoids and benzo-

methadone and buprenorphine significantly re- diazepines in 75% of patients remaining in treat-

duce drug use and improve treatment retention ment) [50].

Although maintenance treatment is consid- 4.2. Maintenance treatment of opioid dependence

ered the gold-standard therapeutic strategy (and

is the focus of this article), a popular approach is

There are multiple determinants of the ef-

that of assisting opioid-dependent individuals to fectiveness of maintenance treatment for opioid

medically withdraw from opioids, a process also dependence, including characteristics of the pa-

referred to as opioid detoxification (Figure 4). tient, the medications used and the way treat-

Both methadone and buprenorphine can be used ment is implemented. The primary focus of this

in reducing doses to assist in achieving medical educational supplement will be to highlight the

withdrawal from opioids. Gradual dose reduc- basic pharmacological considerations that are rel-

tions help to minimise the likelihood of signifi- evant in selecting an appropriate medication and

cant withdrawal and allow time for neuronal re- implementing this option to achieve the goals of

adaptation. Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as therapy. According to the WHO, the following

clonidine can also be used to reduce the severity attributes are essential for treatments to be used

of opioid withdrawal symptoms. In non-tolerant as maintenance therapy in opioid-dependent pa-

patients, the long-acting opioid antagonist nal- tients [113]:

trexone can be used to prevent relapse to opioids

Opioid properties in order to prevent with-

[111]. Both naltrexone and its active metabolite drawal symptoms and reduce craving

6-β-naltrexol are competitive antagonists at the

Affinity for opioid receptors in the brain in or-

mu and kappa opioid receptors, reversibly block- der to diminish or block the effects of heroin or

ing or attenuating the effects of opioids [91]. As other opioids

a result, a person maintained on naltrexone will

Longer duration of action than abused opioid

not experience any of the sought-after positive drugs to delay the emergence of withdrawal and

effects of heroin. Naltrexone maintenance may reduce the frequency of administration

be effective for selected, mildly ill and highly

Oral administration to reduce the risk of infec-

motivated individuals [90]. However, detoxifica- tions associated with injections

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

The following sections present an overview of 4.2.1.2. Treatment – induction

the basic pharmacological and clinical considera-

tions applicable to the use of the three main main-

Induction describes the initial stage of treat-

tenance pharmacotherapy options: methadone, ment when an individual dependent on street

buprenorphine and buprenorphine–naloxone. heroin or other non-prescribed opioids is initiated

The local manufacturer's prescribing information on maintenance treatment. The primary objec-

should be consulted for comprehensive infor- tives of the induction stage are to ensure safety

mation on dosage, administration, precautions, and to retain patients in treatment by preventing

warnings and contraindications.

or reducing the signs and symptoms of opioid

withdrawal, or preventing relapse in non-tolerant

4.2.1. Methadone treatment

individuals or treatment re-starters in the early

phase of use. It is important to carefully explain

intoxicating effects and withdrawal symptoms to

patients, observe them frequently and ensure safe

Methadone was the first widely used opioid- dosing in seeking to achieve these aims. Once in-

maintenance therapy for the treatment of patients ducted safely, the goal is to achieve an optimal

with opioid dependency [29] and its use assisted dose for longer-term maintenance that prevents

a shift in treatment targets for opioid dependency cravings and addictive opioid use.

from total abstinence to long-term maintenance

A comprehensive assessment of patient drug

[106]. Methadone is a synthetic, lipid-soluble, use, medical, psychological and social conditions,

opioid agonist, which acts with similar affinity previous treatment history and current treatment

to heroin at the mu-receptor [47]. Usually ad- goals should be conducted and documented prior

ministered orally, methadone is readily absorbed to initiating therapy. Corroborative evidence of

via the gastrointestinal tract resulting in a high opioid dependence – observed signs of opioid

but variable bioavailability of 40–100% depend- withdrawal or a history of previous treatment

ing on the individual patient [74]. The onset of for dependence – should be established before

therapeutic benefit with methadone is within 30 initiating treatment. Responses to previous treat-

minutes after ingestion, with an average time to ments can also guide treatment decisions, form-

peak of 2.5 hours [41, 67]. Plasma-methadone ing the basis of the initial treatment plan. Such

concentrations continue to rise for 3–4 hours fol- assessments can also be used to monitor progress

lowing oral ingestion and then decline gradually. during treatment [41, 67].

With ongoing dosing, the half-life of methadone

is extended to 13–47 hours, with a mean of 24 4.2.1.2.1. Treatment-naïve patients

Due to its combination of mu-opioid-receptor-

New patients should be dosed with caution

agonist properties, high oral bioavailability and when using methadone in order to safely uptitrate

a prolonged half-life, once-daily oral methadone to a satisfactory dose and achieve steady-state

provides effective long-lasting suppression of plasma concentrations. This approach is neces-

opioid withdrawal symptoms and cravings for sary to mitigate the risks of methadone accumula-

many patients. In addition, as a result of the phe- tion across dosing intervals (due to its prolonged

nomenon of cross tolerance, tolerance to other half-life) and consequent toxicity (including res-

opioids is produced. This means that diminished piratory depression and sedation). The first dose

intensity of opioid effects will be observed, which should be determined for each patient based on

contributes to the reduction in heroin abuse dur- the severity of dependence and level of tolerance

ing methadone maintenance [58].

to opioids, and, if possible, patients should be ob-

I. Maremmani et al.: Basics on Addiction: a training package for medical practitioners or psychiatrists who treat opioid dependence

served for 3–4 hours after the first dose. The first ment. Patients transferring from buprenorphine

2 weeks of treatment are the greatest risk period treatment should be stabilised on 16mg/day or

for methadone toxicity and overdose. During this less for several days prior to transfer. Metha-

time, patients should be observed daily prior to done can be commenced 24 hours after the last

dosing and assessed for signs of intoxication or buprenorphine dose, and the initial methadone

withdrawal. Deaths in the first 2 weeks have been dose should not exceed 40mg. Patients transfer-

associated with methadone doses in the range of ring from naltrexone should be treated as opioid-

25–100mg/day, with most occurring at doses of naïve, as tolerance to opioids is lost after a few

40–60mg/day. Whilst therapeutic maintenance days of naltrexone treatment. Methadone should

doses are typically in the range of 60mg/day or not be administered for at least 72 hours after the

more, the risk of toxicity during methadone in- last naltrexone dose, and the commencing dose

duction requires the use of lower starting doses. should be no more than 20mg [41, 105].

An initial methadone dose of ≤20mg for a 70kg

patient can be presumed safe, even in opioid- 4.2.1.3. Treatment – maintenance

naïve users; this dose will alleviate withdrawal

symptoms in most patients. Caution should be

Typically, effective methadone maintenance

exercised with doses of 30mg or more, and ex- doses are 80–120mg/day. Maintenance doses

treme caution and specialist involvement are higher than 120mg/day may be necessary in some

advisable for doses of 40mg or more [41, 105]. patients, such as those who have a fast metha-

Dose increments of 5–10mg can be considered done metabolism or dual-diagnosis patients,

every 5–7 days as required, with overall weekly while a minority of patients can be maintained

increases no larger than 40mg [41] until a stable effectively on doses less than 60mg/day [15, 32,

maintenance dose is achieved. For individuals 41]. Methadone maintenance doses should be de-

starting treatment who are presumed to have no termined on an individual basis. Patient input to

tolerance, or irregular use at time of treatment treatment decisions, including determination of

initiation, dosages should be low, dose increases dose levels, helps promote a good therapeutic re-

should take not place more often than weekly (at lationship. The optimal maintenance dose should

least until blocking dosages are reached), and reduce opioid cravings and use without produc-

overall increases in daily dose should not be more ing euphoria. Daily administration of methadone

than 10mg. This may be the case for: a) patients is required in order to maintain adequate plasma

who have discontinued treatment recently, and levels and avoid opioid withdrawal. Monitoring

have not yet relapsed into regular drug use; b) pa- drug use can also help assess treatment progress

tients who have just been returned to their natural and may be useful for clinical decision making

environment, with free availability of the opiate [41, 105].

of abuse, without having been started on any ag-

Patients who miss their daily methadone dose

onist treatment while in a protected environment; may be engaging in other drug use or are at risk

c) patients who are not currently tolerant to opi- for leaving treatment. Tolerance to opioids may

ates, but are willing to start some effective treat- be reduced after more than 3 days of missed

ment, or who ask for advice about how to prevent methadone, placing patients at risk of overdose

relapses (diagnostic criteria should be satisfied).

when methadone is reintroduced. If missed for

more than 3 days, methadone should be reintro-

4.2.1.2.2. Patients transferring from other pharmacotherapies duced at half dose, while for more than 5 days

of missed treatment, reintroduction of methadone

When another pharmacotherapy has failed, should be regarded as a new induction [41, 105].

patients may be transferred to methadone treat-

Heroin Addiction and Related Clinical Problems 13 (2): 5-40

4.2.1.4. Cessation of methadone treatment

safety consideration for methadone given its doc-

umented association with QT-interval prolonga-

Patients should be encouraged to remain in tion. On the basis of available evidence, an expert

treatment for at least 12 months to achieve en- panel convened by the United States Center for

during lifestyle changes, with some patients re- Substance Abuse Treatment developed a series of

quiring considerably longer periods. Beyond this safety recommendations for physicians prescrib-

point, no pre-determined treatment-term suits all ing methadone, specifically addressing the need

cases, but benefits are maintained and stability to inform patients about the risk of arrhythmia,

guaranteed by ongoing treatment, while with- assess cardiac history, use electrocardiography

drawal from treatment, no matter how gradual, is for baseline and follow-up assessment, manage

associated with a higher risk of relapse.

risk factors, and be aware of interactions between

Withdrawal from methadone treatment should methadone and other drugs that prolong the QT

be completed slowly and safely, and dose reduc- interval [59].

tions should be made in consultation with pa-

In addition to direct methadone side effects,

tients. Doses should be reduced by 10mg/week some studies have reported that a significant

to a level of 40mg/day, then by 5mg/week. Signs subset of patients (up to a third) may experience

and symptoms of withdrawal may become appar- symptoms of breakthrough withdrawal during

ent as the methadone dose falls below 20mg/day, the 24-hour inter-dosing interval [34]. Failure

with a peak at 2–3 days after cessation of metha- to achieve satisfactory 24-hour withdrawal sup-

done. Supportive care reduces the risk of relapse pression has been linked to individual variation

in the short-term and should be offered for at in methadone pharmacokinetics and the rate of

least 6 months post-methadone treatment [41, decline in plasma concentrations between peak