Kamagra gibt es auch als Kautabletten, die sich schneller auflösen als normale Pillen. Manche Patienten empfinden das als angenehmer. Wer sich informieren will, findet Hinweise unter kamagra kautabletten.

Cut and paste hewlett doc 4

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs) in Developing Countries:

Assessing Opportunities for Expanding Access and Use

Project Team:

Amy E. Pollack MD, MPH John Ross PhD Gordon Perkin MD

"A deeper commitment to contraception, including the IUD, can ease the burden of many health problems in every country. Foundations can highlight the leverage that contraception offers for lessening those burdens. They can advance advocacy at the highest levels and partner with other donors in a common strategy, thus leveraging the investment of USAID and the private sectors commitment."

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Table of Contents

Ranking factors influencing programmatic initiatives supporting access and uptake. 40

Successful and unsuccessful programs: lessons learned. 40

Knowledge and acceptance of the IUD . 41

Status of other IUD revitalization program, research, and advocacy efforts. 44

Case-in-point: The USAID Kenya Mission. 46

SUPPLY ISSUES . 48

III.1 Cost/Benefit . 48 III.2 Product patents, intellectual property and licensing . 48 III.3 Public-Private

Partnership . 49

III.5 Timeline . 52

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS . 54

IV.1 Conclusions. 54 IV.2 Recommendations. 56 IV.3 Specific

VI.1 APPENDIX 1: NUMBERS OF IUD USERS AND OTHER INDICATORS. 65 VI.2 APPENDIX 2: DISCONTINUATION RATES . 68 VI.3 APPENDIX 3. Numbers with Unmet Need by Region, Spacing/Limiting, and Marital Status, 2000 (in thousands) . 70 VI.4 APPENDIX 4. Projections of IUD Use. 72 VI.5 APPENDIX 5: Preferred method of contraception for future use . 74 VI.6 APPENDIX 6. Percent of Married Women Ever Using the IUD, by Age and Region 76 VI.7 APPENDIX 7. Percent of Currently married Women Who Know Each Method. 79

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

List of Figures:

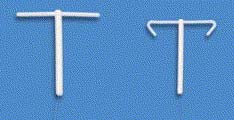

Figure 1. Images of six IUDs. 12

Figure 2. Advantages of the TCu 380A . 13

Figure 3. Disadvantages of the TCu 380A. 14

Figure 4. Advantages of the LnG IUD. 17

Figure 5. Disadvantages of the LnG IUD . 20

Figure 6. Relation of Total Prevalence to IUD Prevalence . 28

Figure 7. IUD Sources of Supply by Sector . 36

Figure 8. Private involvement and IUD prevalence. 36

Figure 9. Dependence of IUD Prevalence upon IUD Access. 39

Table 1. Principle clinical trials documenting the contraceptive efficacy of the LnG IUD . 18

Table 2. Selected health benefits/disease protection from using the levonorgestrelIUD . 19

Table 3. Cumulative net probabilities of IUD use discontinuation . 23

Table 4. The consequences of additional exposure to pregnancy as impacted by continuation

Table 5. Historical Experience for Increases in IUD Prevalence . 29 Table 6. Projections of IUD prevalence, users, and adopters at a half percent rise per year in IUD

Table 7. Countries Classified by Total Prevalence and IUD Prevalence . 34 Table 8. (DKT) 2004 Social Marketing Program Sales from all sources for IUDs. 37 Table 9. Percent Using the IUD, by Age, No. of Children, Residence, and Education. 43 Table 10. Ever Use of the IUD, by Age and Region . 44 Table 11. Knowledge of IUD and Other Methods, by Region . 44 Table 12. WHO Cost Estimate and a timeline for Phase III Clinical Trial of a New LnG/Mirena

Table 13. Sample matrix of country case studies . 59

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

FORWARD

At the beginning of 2006, the Hewlett Foundation's Population Program sought an assessment of

the potential of the IUD as a contraceptive method in developing countries and ways to improve

IUD availability, acceptance, and effectiveness. A team of three consultants—Amy E. Pollack,

John Ross and Gordon Perkin—conducted an analysis during the first part of 2006 on: (1) public

health benefits of the IUD; (2) programmatic factors influencing IUD use; (3) supply issues,

including analysis of public-private partnerships; and finally (4) options for Foundations

considering support for IUD programs. This report is primarily geared toward the donor

community, especially private foundations, and may also be of interest to program planners,

researchers, and advocates.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

I. Overview

The intrauterine device (IUD) has long been recognized as an inexpensive, highly effective,

long-acting, reversible method of contraception. Even though it is ideal in so many ways, the

history of its development reflects continual adaptations to minimize the side effects that lead to

early discontinuations, and to maximize both contraceptive and non-contraceptive health

benefits. The IUD should play a greater role than it does today in parts of the world, and

especially sub-Saharan Africa, where fertility rates, unintended pregnancies, and unmet need for

contraception are high. Those same parts of the world struggle against severe health problems

and health system shortcomings that highlight the non-contraceptive (health) advantages of a

hormonal IUD if it could be deployed widely. However, despite past efforts, many parts of the

world in greatest need have surprisingly low rates of IUD use. Understanding the clinical,

setting, and programmatic barriers should inform future investments for the global expansion of

IUD use and new IUD product development.

This report initially reviews the history, clinical aspects, and some of the broad "setting"

characteristics that have most likely influenced IUD use. The second section analyses

programmatic issues that have equal or greater influence on overall use. The third section

analyzes supply issues, examining options for increasing uptake of the TCu 380A or expanding

the marketplace through either a new IUD or greater access to the LnG IUD currently

unavailable in developing countries. Finally, we present an assessment of options for

Foundation support for expanding IUD uptake in the future based on our findings. The report is

meant to be an inclusive review of both published and unpublished findings. Although we were

asked specifically about recommendations as they apply to sub-Saharan Africa, the report is not

limited in that regard. We include our recommendations for development and introduction of a

new IUD for the public sector that would be cost-effective and offer new health benefits. A time

frame for development and clinical assessment of a new IUD is included in the report (see Table

12 on page 54).

II. Current IUD use

WHO estimates that approximately 160 million women worldwide use IUDs today. China has an

estimated two-thirds of these users, or 96 million. Only a small percentage of current users are in

eastern or western Europe or other industrialized countries (10%). The remaining 24% are in

developing countries other than China, concentrated in Vietnam, Egypt, Indonesia, India,

Uzbekistan, and Turkey. These six countries alone contain half of all users in developing

countries excluding China.

A remarkable geographic pattern of IUD users exists. Most developing countries fall into

clusters, which show widely different determinants of use. In the former USSR republics, the

absence of other contraceptive options was paired with strong clinical capacity; in China and

Vietnam it was government control; in North Africa and the Middle East it was an aversion to

sterilization, considerable clinical capacity, and a cultural acceptance of the IUD. In Latin

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

American and most of Asia, however, the pattern is more idiosyncratic. Where clinical services

and trained providers are inaccessible and other method options sometimes exist, IUD uptake is

negligible, as is the case across all of sub-Saharan Africa.

III. Clinical characteristics that influence IUD use

Several types of IUDs exist, however the most widely available IUD is the TCu 380A. It is

highly effective and long acting, easy to insert, and has a low complication rate. No new IUD is

likely to offer a significant improvement over its essential qualities. However, side effects that

lead to early discontinuation, such as increased bleeding or menstrual pain, could be improved

upon, and would likely improve its continuation rate. That would also increase the pool of

satisfied clients (improved provider training and better client counseling should have a similar

effect, on any IUD).

The Mirena LnG IUD, its wider distribution limited by cost more than anything else, compares

favorably with the safety and efficacy profile of the TCu 380A, although it is more difficult to

insert and has a shorter approved duration of use. Moreover, studies that compare the two IUDs

suggest that despite a decrease in irregular and menstrual bleeding, continuation rates are lower

than with the TCu 380A, which may reflect user concerns about induced oligomenorrhea or

amenorrhea and a different risk ratio faced by developing country women. A LnG-induced

decrease in uterine blood loss related to either menses or other intrauterine abnormalities

(especially in the peri-menopause) could provide an important therapeutic public health benefit,

especially in sub-Saharan Africa where anemia rates are remarkably high. However, evidence

that the LnG IUD could significantly impact the multifactoral type of anemia present in the

region is very limited to date.

Several newer hormonal IUDs are under development, which include design changes to improve

ease of insertion and possibly alter associated pain or bleeding pattern. Duration of use remains

limited compared to the TCu 380A's 10-year approval (tested for 14 years). Through new

product development, a negotiated public sector price should be possible that would remove the

cost barrier to expanding the IUD market, with a greater diversity of products.

IV. Setting and programmatic characteristics that influence IUD demand and use

Our review of setting and program issues that have influenced IUD use historically points to both

conditions for "success" and barriers for "failure." Invariably, the capacity of the health sector is

key, that is, socioeconomic and infrastructure conditions that constrain access to services.

Equally, policy positions and the vigor with which they are enforced matter greatly, such as, the

shared commitment to the IUD at central, clinic, and provider levels including resources for

ongoing training, information and education, and consumer marketing). The private medical

sector cannot be ignored; it has its own life and can be independently important. Cultural forces

are relevant in some cases. All these factors influence the contraceptive method mix.

"Demand" for a specific method therefore cannot be understood in isolation. While IUD

prevalence is high wherever IUD access is high, "access" is usually a marker for other program

features as well. USAID's IUD revitalization project notes the transition in Kenya's method mix

away from IUD use and toward injectable use, without an increase in total contraceptive

prevalence. Sterilization use also declined in the same period (1998-2003). For these clinical

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

methods, it is impossible to know whether the declines reflect the increasingly stressed health

care delivery setting, the influence of myths about IUD safety, or the appeal of the injectable's

special features. Ultimately, clinic based services that require a trained provider and a medical

procedure (whether a pelvic exam or surgery) rest on a different infrastructure and programmatic

commitment than commodity supply and distribution, whether for pills, condoms, or injectables.

Although some countries in Asia or Latin America neglect the IUD, every country in sub-

Saharan Africa does so, with only very slight differences by education or residence categories. In

addition, although the IUD is considered a safe and effective method for use by HIV infected

women, it provides no STI protection and its promotion has been called into question where

improved barrier methods are badly needed.

In recognition of the underutilization of the IUD, two distinct programmatic efforts are

underway. Certain USAID cooperating agencies have, through various funding streams,

organized to revitalize the IUD through both operations research and program/IEC initiatives,

focused chiefly on sub-Saharan African countries but with exceptions in other regions.

Preliminary results confirm the nature of "macro" level barriers that exist within the health

sector. However, the growing private sector in some countries may present an opportunity for

growth and should be closely followed. While these social marketing, social franchising, or

private clinic services may not reach the lowest socioeconomic quartile, they can, through

consistent commodity supply and trained, less biased providers, expand IUD use within their

own markets. Increasing, the pool of users in that way may quicken interest and familiarity with

the IUD in general.

V. Affordability of a hormonal IUD and its influence on access and supply

In recognition of the significant health benefits of the hormonal IUD, the question was raised as

to whether public sector pricing (removal of the cost barrier) of either the existing Mirena LnG

IUD, a generic version, or a new hormonal IUD could not only provide public health benefits but

also catalyze increased interest in IUD use. Based on current manufacturing limitations a public-

private sector partnership would allow for a public sector price of under USD $5.00 for one

option only- the development of a new IUD. Although this option would require an up front

investment to support certain aspects of the necessary clinical research, it would allow for a re-

design to address design issues associated with the Mirena. The product price differential, in

comparison with the TCu 380A, would be minimized if spread over the first five years of use.

Introduction of this new IUD could be 5 to10 years away, and would be a strategic investment

requiring long-term vision and donor commitment. Such an investment would be highly likely to

succeed in providing a new, highly effective contraceptive option with associated significant

health benefits to women worldwide at a low public sector investment in return for an acceptable

public sector price. In the foreseeable future, however, it is clear that, a new IUD will not change

the landscape of negligible IUD use in sub-Saharan Africa.

VI. Recommendations Development of an affordable hormonal IUD: This should be an area of consideration for

long-term investment, even though there is a lack of evidence regarding the public impact that

would significantly impact use in sub-Saharan Africa. The innovation is one that promises to

change or save lives if deployed on a large enough scale; it offers the potential of expanding IUD

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

use in regions other than sub-Saharan Africa. It should be noted that obtaining a guaranteed public sector price is probably a time-limited option, one that requires a prompt commitment if this objective is to be realized.

If this recommendation is endorsed, key areas of support could include preparation for case

studies in selected countries matched to: 1) WHO clinical trial sites; 2) potential for both private

and public sector expansion; 3) acceptability for ICA donated Mirena LnG. The published case

studies would support advocacy efforts at the national level once trials are completed and

introduction is underway.

Large scale support for promotion or expansion of IUDs in sub-Saharan Africa: Efforts

should focus on continued support for those organizations working with USAID on revitalization

projects. Key areas of support could include: 1) full project evaluation of the revitalization

projects, beyond the possible termination of vulnerable USAID funding; and 2) documentation

and widespread dissemination of evaluation findings from these projects to inform further

investments and program innovation.

Support for Private Sector: Continued or new investments to support expansion of IUD use in

the private sector in selected countries. Again, documentation and widespread dissemination of

program results to inform further investments and program innovation is recommended. A

specific investment in social marketing/franchising projects with the intention of further

describing private sector capacity and replicable models is worth considering.

Identify a grantee to design a collaborative project taking into account currently completed or

proposed case studies of IUD availability, acceptability, and use, and identify 2-4 additional

countries to prepare for the new hormonal IUD introduction.

Research Priorities: Consider supporting the following: Operations research demonstrating

service delivery implementation and demand for the method would be a contribution to the

literature and inform some settings where advocacy requires an evidence base. Research of the

significance of amenorrhea in different populations and how to counsel and communicate about

the advantage of the new IUD to both providers and clients.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

INTRODUCTION

The intrauterine device (IUD) has long been recognized as a highly effective, long-acting,

reversible method of contraception. Ideal in so many ways, the history of its development

reflects the widespread interest in continual revision of the device concept in an effort to

minimize side effects leading to early discontinuation, and maximize both contraceptive and

non-contraceptive health benefits. In parts of the world where fertility rates, unintended

pregnancy, and unmet need for contraception are high, the IUD should play a greater role in

providing a safe and highly effective contraceptive option than it does today. Despite past efforts,

parts of the world in greatest need have surprisingly low rates of use. This may be because both

clinical aspects of the IUD (foreign body, associated menstrual changes) and programmatic

barriers (the need for the commodity, a procedure, training, and a motivated provider) collide

and dilute the ideal aspects of the contraceptive impact itself.

This paper reviews the history, geographic distribution, and clinical aspects of IUDs that

influence IUD use. The second section analyzes programmatic issues that have equal or greater

influence on overall use. The third section addresses supply issues, examining options for

increasing uptake of the TCu 380A or expanding the marketplace through either a new IUD or

greater access to the LnG IUD currently unavailable in developing countries through lower

pricing. Finally, we will present an assessment of options for Foundation support for expanding

IUD uptake in the future based on our findings. We include our recommendations regarding

development and introduction of a new IUD for the public sector that would be cost effective and

offer new health benefits. A time frame for research and development is included in the report

(see Table 12 on page 54).

History of IUD development and use

IUD use was first reported in the 1800's and in 1902 Hallwig designed a pessary that had a stem

extending into the cervical canal that was marketed for self-insertion. This was followed by

Richter's silk and catgut ring covered in nickel and bronze wire and then Pust, who developed

another ring for intrauterine use, utilized during WWI. Problems with infection attributed to the

tail string led to the next innovation, the Graefenburg ring, in 1930. Contraception in Germany

was highly discouraged; Graefenburg was exiled, leaving the problem of high expulsion rates

unaddressed. In the 1960's there was revived interest in the IUD and a plastic device with an

inserter was developed. The first reported international conference on IUDs took place in 1962,

where different products were compared and the Lippes Loop was presented, followed shortly by

the Tatum T with added copper (contraceptiononline 2006). The Dalcon Shield, introduced in

1970 was designed to decrease expulsion, however high rates of infection attributed to its

multifilament tail led to its discontinuation and the stigma associated with IUD use in the US is

still prevalent today.

Trends in IUD use in the rest of the industrialized world are not as dismal but remain

disappointing. Based on 2004 United Nations data, Eastern and Western Europe represent 4-5%

of global IUD use, despite a greater diversity of types of IUDs that have been approved for use

than in the US (Wildemeersch 2003). IUD use in the United States is very low; estimated at 2%

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

in 2002 (Mosher, 2004). Recently, an increase in evidence supporting the use of the LnG IUD

for non-contraceptive benefits such as treatment of menorrhagia in the peri-menopause has lead

to uptake in use preferentially in older women (Hurskainen R 2004). In addition, the

manufacturer reports increased uptake in the US in the same demographic market for treatment

of menorrhagia or for use in menopausal women as hormone replacement therapy (Bronenkant

L., personal communication 2006). This increase in use does not appear to have influenced

provider bias against use in younger contraceptors in the US, at least not yet. Unlike the situation

in the global public sector markets, the cost differential between the TCu 380A and the Mirena

LnG IUD is small in non-subsidized developed country markets.

WHO estimates that approximately 160 million women worldwide use IUDs today. China has an

estimated two-thirds of these users, or 96 million. Only a small percentage of current users are in

eastern or western Europe or other industrialized countries (10%). The remaining 24% are in

developing countries other than China, concentrated in Vietnam, Egypt, Indonesia, India, and

Uzbekistan, and Turkey – those six countries alone contain half of all users in developing

countries excluding China (see

APPENDIX 1).

A remarkable geographic pattern of IUD users exists. All developing countries fall into the

following clusters, which show widely different determinants of use rates. They also help to

identify programmatic reasons for greater or lesser uptake. The percentages below reflect the

population of women using contraception.

1. The former USSR Republics: the five Central Asian Republics have high use (25- 56%),

as does the cluster of Moldova, Belarus, Ukraine (19% - 34%) and most probably Russia. Why? We can speculate that in the absence of hardly any contraception, the IUD entered the scene as fitting the established medical infrastructure, the weakness of the private sector, the unreliable supply lines for pills or injectables, and the pressures to replace abortion with an alternative. Formal IUD targets did not play a role.

2. At the other extreme are China and Vietnam, also with high use (36% - 38%) but for

different reasons. In these countries, intense policy and programmatic pressures for the method (along with sterilization in China) operated. Other options, with the exception of abortion, were less available. Consequently, little is known about what public preferences would have been if a range of contraceptive choices had been available.

3. In the Middle East, including Egypt, Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Tunisia, use is

moderate to high (15%-36%). Again, formal targets did not play a role. The antipathy towards sterilization left a vacuum for long-term protection, and the medical communities were sufficiently strong to provide services. In Egypt at least, the private medical sector took up provision of the IUD. These countries are also more urbanized than many others, a factor contributing to higher IUD use.

4. The IUD experience in Latin America is mixed. Cuba is an exception with a very high

rate of 44% using the IUD; it has a unique medical system. Eight countries including Mexico, Honduras, Costa Rica, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, and Peru have moderate user rates of 10%-14%. Others are low, especially Brazil, where the IUD is almost unknown at only 1% using it. The reasons for the uneven pattern across Latin America are obscure.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

5. The Asian pattern is one of low to negligible use, apart from China and Vietnam. Few

countries exceed 4% using IUDs, including the highly populated countries of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. The reasons differ greatly, from India's preoccupation with sterilization to Pakistan's program wide weaknesses to Bangladesh's low clinical capacity. Broadly, adoption rates are very low, however there are states in India where IUD prevalence reaches 7% (reasons remain unclear) and in Pakistan a social marketing franchise program (PSI's Green Star program) is slowly expanding IUD use through the private sector. Low user rates of 6%-8% are found in Iran and Indonesia. A decline from 13% to 6% occurred in Indonesia over some years as the injectable rose sharply.

6. Across all of sub-Saharan Africa there is consistently low use: no country exceeds 3%.

Further, the main subgroups according to age, family size, education, and residence are consistently low, so low that use pervades the whole population. Causes of low use are apparently multiple: neglect of the method at the policy/program level, poor infrastructures and low clinical capacity, damaging rumors, female prejudices against an intrauterine foreign body, fear of infection or other complications, and either misinformed or reluctant providers. In any case, the universality of the IUD absence is striking compared to other regions.

In summary, the global pattern of IUD use is a disparate one, and reflects very different causes at work. The overall effect, for total contraceptive use, presents a pattern that is somewhat less puzzling than the odd geographic pattern for each individual method. As a rule, whatever contraceptive option is easiest to obtain, for whatever reasons, tends to dominate.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

SECTION I

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MOST

AVAILABLE IUDS

I.1 Types of IUDs

Two highly effective intrauterine devices (IUDs) are available in the global market today. The

TCu 380A ( TCu 380A)(ParaGard, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) and the

levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LnG IUS or IUD)1 (Mirena, Berlex Inc., Montville, New

Jersey) are currently available in over 100 countries. Figure 1 provides images of these two

IUDs. The TCu200, and multiload Cu 250 and 375 are still listed on the UNFPA commodities

list but because of the proven higher effectiveness of the TCu 380A in comparison, and WHO's

recognition of it as the first choice among the copper bearing devices, these alternatives will not

be specifically addressed in this paper (WHO 1997).

Several other IUDs, also shown in Figure 1, are currently under development or have been

introduced in Europe including the Gynefix IUS and the mini Gynefix IUS (Van Kets H, 1997),

FibroPlant (Wildemeersch 2002), the Femilus™ and Femilus™ Slim (Wildemeersch 2005),

and the Flexi-T (Prosan).

Figure 1. Images of six IUDs

TCu 380A Mirena

Femilis™ Femilis Slim™ Gynefix® IUD In Situ

1 Mirena® is referred to as a levonorgestral-releasing intrauterine system, 20 ug/day. The product monograph specifically indicates that the use of the term "intrauterine system" should differentiate it from the intrauterine contraceptives (IUDs) of the past. In this document we will refer to either Mirena, or the LnG IUD (in this case the same thing unless indicated otherwise).

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

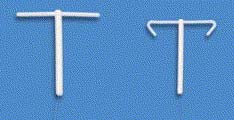

Figure 1 (continued).

Mirena (above) and Flexi-T (below) for size comparison

I.2 TCu 380A IUD – Advantages and Disadvantages

The TCu 380A is a polyethylene device with barium sulfate added to allow for visualization by

x-ray. The device measures 36 mm long by 32 mm wide, with a 3 mm bulb at the base of the

stem. Each of the horizontal arms is covered with a copper sleeve and copper wire is wound

around the length of the vertical stem for a total surface area of copper of about 380 mm². A

monofilament double strand polyethylene string is tied to the bulb at the base for use in removal.

The Cu T380A has a 7 year shelf life, and is approved for 10 years of use. Figures 2 and 3

outline advantages and disadvantages of this IUD.

Mechanism of Action

IUDs in general work by preventing effective sperm function and therefore fertilization (Rivera,

1999). The TCu 380A releases copper ions and causes an inflammatory response with associated

local increase of prostaglandins, white blood cells, and change in the normal fluids present in the

uterus and tubes (WHO 1987; Saleem 1996).

Figure 2. Advantages of the TCu 380A

• Highly effective

• Protective against ectopic pregnancy

• Probable protective effect against

endometrial cancer

• Long lasting, convenient and safe

• Cost effective Adapted from Contraceptive technology 2004;

Hubacher and Grimes 2002

Effectiveness The TCu 380A is well known for its high efficacy- the aspect of contraceptive effectiveness attributed to the method itself. Pregnancy assays that are highly sensitive and measure the lowest

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

levels of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) in the blood indicate that fertilization and implantation do not occur in TCu 380A users (Wilcox, 1987). Because the IUD is not user dependent, once placed correctly, effectiveness is high with a failure rate of less than 1 per 100 woman-years and cumulative failure rate at 12 years of 2.2% per 100 women (Sivin 1987). This rate is comparable to the cumulative 10-year failure rate of female sterilization in the US of 1.9 per 100 women.(Peterson 1996). The TCu 380A is FDA approved for 10 years of use however studies indicate that it is effective for 12 years (WHO 1997) and unpublished data indicates the same high efficacy in a small study population after 20 years of use (Sivin 2006 pre-publication communication).

Ectopic Pregnancy

The 12-year cumulative ectopic pregnancy rate of 0.7 makes the TCu 380A protective against ectopic pregnancy compared with non-contraceptive users. (Franks 1990 ).

Non-contraceptive health benefits

The TCu 380A is a non-hormonal method that provides an option to women with contraindications to oral contraception or other hormonal methods, and an equally effective option to women who are not sterilization candidates. There are now two studies that report a statistically significant protective effect against endometrial cancer in copper IUD users (Hubacher D and Grimes DA 2002).

Figure 3. Disadvantages of the TCu 380A

• Provider dependent method • Spontaneous expulsion

• Perforation • String loss

• PID risk with insertion

• Does not protect against STI/HIV Adapted from Contraceptive Technology 2004

Expulsion / Perforation/ String loss Although the IUD is highly effective, proper placement is critical to long-term effectiveness. Spontaneous expulsion of the TCu 380A occurs in 2-10% of users within the first year (Zhang J 1992). Rates were higher in adolescents (and decreased with increased age), women with heavy menstrual flow, and women with a history of cramping pain (dysmenorrhea), with a 30% chance of repeat expulsion (Bahamondes 1995). Expulsion can be "silent" (without any pain) or associated with bleeding and cramping. WHO's RHR 2003 technical report includes interim data from ongoing multicenter IUD safety and effectiveness studies. The cumulative net expulsion rate is reported as 11.2 per 100 women after 10 years and this rate is consistent with their previous 12 year published study of the TCu 380A of 12.5%, with most occurring in the first few years (UNDP/UNFPA Contraception 1997).

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Perforation2 is rare and occurs at the time of insertion. In experienced hands the estimated perforation rate for copper IUDs is 1 per 1,000 (WHO 1987). There is no evidence that the IUD "migrates" out of the uterus following normal insertion. The myths prevalent in parts of Africa may be the result of outcomes from poor insertion resulting in undetected perforations (Grimes, 2004A). Because copper causes inflammation and can cause scarring in the abdominal cavity near the bowel, bladder and ovaries the copper bearing IUD should be removed. This is most easily accomplished via laparoscopy, however, in places where no skilled provider is available, abdominal surgery may be required.

Lost strings can signal a perforation, undetected expulsion or simply ascension of the strings into the uterine cavity. Where ultrasound is available, identification of the IUD in the uterus and guided removal using local anesthetic at the cervix is possible. When ultrasound is not available the provider must assume an undetected expulsion and either explore the uterus blindly, and/or provide an alternative contraceptive method. There is no published data on rates for lost strings.

All IUDs are provider dependent methods. Both expulsions from improper placement and perforation rates can be minimized by use of standardized training and skilled providers (Chi, 1993; Harrison-Woolrych 2002). Published studies do not report widely on the impact of using less experienced providers on rates of either of these complications. However, provider shortages in many geographic locations, and in particular, in sub-Saharan Africa, make this more of a challenge than simply investing in better guidelines development and training.

PID By far the most controversial issue related to IUD use has been concern that the IUD increases the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. In the WHO-sponsored IUD trials, the risk of upper genital tract infection was limited to the first 20 days after insertion (Farley TM 1992). A recent systematic review of the literature attempted to assess the added risk of PID following IUD insertion in women with cervical Chlamydia or gonorrhea (Mohllajee 2006). This analysis is complex because of both the nature of the problem and by necessity, the study design; Chlamydia infection is often asymptomatic and it is not possible to randomize infected and uninfected women for IUD placement. Taking into account both cases - the overall increased risk of PID in the modern IUD user has been estimated based on observational studies and appears to be low, even in environments where the background prevalence of STIs (Chlamydia and/or gonorrhea) is high, ranging from 0.6 per 1,000 women (International Collaborative Post-marketing Surveillance of Norplant. 2001) to 1.11% in Nigeria (Sinei 1990) and 1.9% in Kenya at 30 days after insertion of the TCu 380A IUD(Walsh 1994). Because the rate of PID in infected non-IUD users is unknown in these groups, it is impossible to determine the added risk (Shelton 2001).

It is important, however, to consider that almost all other contraceptive methods (condoms as more inclusive barriers, and hormonals and sterilization against PID) do provide some protection against STIs or PID. The copper IUD does not.

2 Perforation is a hole in the wall of an organ; in this case the IUD is accidentally inserted into the wall of the uterine muscle.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

HIV positive women

Limited research reporting on safety of the copper IUD used in HIV infected women suggests that complication rates are comparable in HIV infected and non infected IUD users.(FHI 2005).

Nulliparous or nulligravid woman Although there is no contraindication to use of the TCu 380A in a women who has never been pregnant or given birth (WHO medical eligibility criteria category 2)3, there may be a higher rate of mechanical problems associated with use. Expulsion rates are higher in adolescents, probably most related to their nulliparous state (Bahamondes 1995). Insertion is also more difficult related to the small diameter of the cervical canal (Grimes 2004). Use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prior to insertion or even cervical dilators overnight can help prevent vasovagal reactions to insertion but these interventions may not be practical in all low resource settings.

Side Effects - Bleeding and Anemia

The most common medical indication for discontinuation of the TCu 380A is irregular bleeding.

Irregular bleeding in the first several months of use is common but decreases over time. Women

using the TCu 380A also often have heavier menses than the non-user. If the bleeding is

significant, the health care provider needs to discern whether it is IUD-related or due to an

undiagnosed pregnancy, an infection, or another intrauterine disorder. This in itself is an added

intervention, and in a compromised health service delivery setting where access to providers is

severely limited presents a barrier to IUD selection and continuation.

Iron deficiency anemia can be caused by poor nutrition and/or blood loss in industrialized countries, however it is more broadly multifactoral in developing countries with high prevalence of malaria, hookworm and other chronic disease and infections (HIV included). Actual blood loss associated with TCu 380 use is less than with older model IUDs. The marginal impact on hemoglobin level, studied in populations with normal levels of 12g/dl or greater, is small in the range of -0.5 g/dl occurring during early use may equilibrate over time with longer use (Andrade AT, 1987). The WHO listed Cu IUDs as category 2 –advantage outweighs risk for use in women with anemia. In any event, the TCu 380A does not decrease blood loss associated with menses or other intrauterine disorders. It is unclear what impact the small but steady increased menstrual blood loss associated with use has in a population with a high endemic rate of multifactoral anemia.

I.3 The LnG IUD - Advantages and Disadvantages

The Mirena is a plain plastic T-shaped frame, 32 mm long and wide and impregnated with

barium sulfate making it radiopaque. The steroid reservoir around the stem is a cylindrical

mixture of 52 mg of levonorgestreland polydimethylsiloxane, covered by a membrane that

allows for release of 20ug/day of LNG. Removal strings are attached to the base. MIRENA has a

3. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive use (2004)(MEC) is one of the World Health Organization's two evidence based guidelines on contraceptive use, intended for policy-makers, program managers, and the scientific community. A designation of category 2 is "a condition where the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks".

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

3-year shelf life and is effective for at least 5 years. Figures 4 and 5 outline the advantage and disadvantages of this IUD.

Mechanism of Action Mirena is a steroid releasing device that acts locally to cause high levels of levonorgestrelin the endometrial tissue that lines the uterus, but low levels of systemic hormone. It has a minor effect on ovarian function. Both factors of high local impact and low systemic absorption are important in understanding the ultimate advantages of any levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Local effects include thickened cervical mucus that slows the passage of sperm and a direct suppression of the endometrium causing it to atrophy (dry up) and become unresponsive to estrogen. The progestin effects also cause a decrease in sperm motility in both the uterus and the tubes. This is the result of the same sterile foreign-body reaction noted associated with the T Cu 380A that impedes ovum and sperm transport and fertilization; the LnG IUD also induces production of a glycoprotein that inhibits sperm-egg binding (Mandolin 1997). Together the local effects are responsible for its highly effective contraceptive action (Jensen 2005) and other non-contraceptive effects.

Figure 4. Advantages of the LnG IUD

• Highly Effective

• Protective against ectopic pregnancy

• Possibly protective against PID •

Decreases menstrual/uterine blood loss

• Causes amenorrhea in >20% of users

• Safe, long lasting, convenient

Adapted from Contraceptive Technology 2004

Effectiveness Multiple randomized multicenter studies have confirmed the long-term efficacy of the LnG IUD and report a 1 to 7-year failure rate of 0 to 1.1 in women across all age ranges including those most fertile in the group under 25 years of age (Jensen JT 2005). In several large studies (Table 1) there was no significant difference in contraceptive efficacy between the TCu 380A and the 20 ug per day LnG IUD.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Table 1. Principle clinical trials documenting the contraceptive efficacy of the LnG IUD

Taken from Jensen 2005

Ectopic Pregnancy Because of the LnG IUD's high efficacy rate, it is also highly protective against ectopic pregnancy when compared to non-contraceptive users. The US ectopic pregnancy rate is estimated to be 3-4 per 1,000 women-years in non-contraceptors compared to an estimated rate of 0.2 per 1000 women years in LnG IUD users (Sivin 1991)

PID As stated previously, PID rates are low among TCu 380A users and the same is true for LnG IUD users. Rate comparisons against the TCu 380A are shown in Table 2 and are favorable in large trials. In another trial in Scandinavia PID was diagnosed in 0.9% of over 2,000 study subjects using the LnG IUD compared to the overall incidence of PID in the general population of 2.1%.(NDA 21-225; Kani J 1992). This in itself is not enough to determine a protective effect but suggests that there is no added risk. The fact that there is biologic plausibility for protection because of the added barrier provided by progestin induced thickening of cervical mucous is important, an effect also noted in oral contraceptive users (Jonsson 1991). In addition, atrophic changes of the endometrium also caused by the local progestin effect may be protective(Hubacher and Grimes 2002).

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Table 2. Selected health benefits/disease protection from using the levonorgestrel IUD

Taken from Hubacher and Grimes 2002

HIV positive women The LnG IUD does not offer any known protection against cervical infection from sexually transmitted diseases, or any protection against the acquisition of HIV. Although it is unlikely that the IUD's progestin effects add risk for acquisition or transmission of HIV, the specific impact of locally released progestin (as opposed to oral contraceptives or injectables) has not been studied. The issue of impact of progestin contraceptives more broadly and HIV acquisition was addressed recently at an Africa regional meeting where unpublished data were reviewed and found to be difficult to interpret in general application4. Based on the current WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria (WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria 2004), progestin contraceptives, including the IUD, are not contraindicated in HIV+ women. The LnG was not specifically addressed.

Bleeding and anemia The LnG IUD's local effects caused by the impact of levonorgestrel on the endometrium leads to a measurable decrease in menstrual blood loss (Anderson 1994, Suvisaari J, Lahteenmaki P 1996) and an increase in hemoglobin levels over time. Four studies address actual measures of decreased blood loss as indicated in Table 2. The data from these studies also show a decrease in hemoglobin levels with TCu 380A IUD use. The significance of the measurable increase or decrease is unclear in populations with multifactoral anemia as described above.

The impact of endometrial suppression on menstrual blood loss in LnG IUD users is notable

4 Hormonal Contraception and HIV: Science and Policy; Africa Regional Meeting Nairobi 19-21 September 2005. World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/stis/hc_hiv/nairobi_statement.pdf

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

within the first 2 months of use and sustained. In one single-center follow-up study, 25% of 250 women had irregular spotting as opposed to normal menses at 6 months post insertion, and 44% had amenorrhea. At 24 months, 11% of women continued to have irregular spotting and 50% of women reported amenorrhea (Hidalgo M 2002). Two large multicenter randomized trials reported an amenorrhea rate of 17% at one year and 30% at 2 years (Bavega 1989, Sivin 1994).

Quantifying and characterizing menstrual pattern changes is difficult in diverse populations. Although there is an unquestionable decrease in the volume of menstrual blood loss, the irregularity of the resulting bleeding pattern (referred to as "breakthrough bleeding") caused by thin walled blood vessels in the affected endometrium reported in LnG IUD users can be considered a disadvantage. Irregular spotting is most significant during the first few months of use. Discontinuation rates are affected by both initial but also persistent irregular bleeding (WHO ATR 2003) because of both provider and client concern that the bleeding reflects a problem that needs to be diagnosed and resolved (Jacobson 2006, Davie 1996). The changes in menstrual pattern are rapidly reversible with IUD discontinuation (Xiao B 2003).

The LNG IUD has most recently been successfully marketed and used to treat menorrhagia. The above studies address the issue of menstrual disruption in the normally menstruating woman. However, local application and impact of progestin on the endometrium is an important intervention for women who bleed too much due to age related changes of the endometrium or certain benign but problematic pathologic changes. Most of recent publications on LnG IUD use point to the almost perfect therapeutic match for women approaching or in menopause. Several studies indicate that the LNG IUD provides a non-surgical alternative to ablative therapy or hysterectomy for many women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding, uterine myomas, and adenomyosis (Stewart 200, Fedele 1997), These are problems that a percentage of all women suffer from regardless of ethnic background or socioeconomic class. All surgical procedures carry associated risk, and this is especially true in developing countries.

Figure 5. Disadvantages of the LnG IUD

• Provider dependent method

• Spontaneous expulsion

• PID risk with insertion (unknown)

• Does not protect against STI/ HIV

Adapted from Contraceptive Technology 2004

Expulsion/Perforation/String loss It is difficult to estimate ease or difficulty of IUD insertion. That said, many providers acknowledge the greater level of insertion difficulty related to the insertion method design associated with the LnG IUD compared with the TCu 380A. Data do indicate that experience with insertion (numbers of insertion per provider) affects rates of perforation for all IUDs. This inverse relationship (less experience/higher perforation rate) is independent of whether the

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

provider is a physician versus mid-level provider (Harrison-Woolrych 2003) but points to the importance of ease of insertion by design. Until recently most data regarding perforation and expulsion of the IUD were collected in expert centers and were specific to the copper IUDs. With increasing introduction and uptake, new data demonstrate not only the risk of both with the LnG IUD but also the risk of complications associated with the resulting intra-abdominal location, once thought to be of much less concern than with the copper IUDs. Other non-medicated, non-copper bearing IUDs used in the past (that had higher failure rates) were not considered a risk if left inside the abdomen following perforation. However, more like the copper bearing IUDs, the LnG IUD continues to release progestin following perforation and presents a problem. Although a perforation can go unrecognized for months or even years, intra- abdominal scarring or adhesion formation can occur and is considered an indication for removal (Van Houdenhoven 2006).

A recent retrospective study from the Netherlands reported a perforation rate of 2.6/1,000 LnG IUD insertions. Previous studies of uterine perforation related to several of the copper bearing IUDs estimated the incidence of perforation of 1 per 1,000. Risk factors for perforation include the experience of the provider however it seems that perforation is less likely to occur if a withdrawal rather than a push out technique (as is the case with the Mirena LnG IUD) is used (Van Houdenhoven 2006). This is important when considering investment in a generic Mirena vs. the development of a new device that addresses this concern.

PID As reviewed above, there is a small increased risk of PID for the 20 days following IUD insertion. Studies documenting this did not include the LnG IUD, however, because this risk is believed to be related to vaginal contamination during insertion there is no reason to believe that the risk would be different for the LnG IUD.

I.4 Additional clinical considerations

IUD failure and intrauterine pregnancy

Although both the TCu 380A and the LnG IUD are very highly effective they still have failures.

As mentioned, all failures should raise alarm about the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, a life

threatening circumstance in environments where access to health care is minimal (such as rural

parts of SSA, where, as an indicator of access to surgery, obstetric fistula rates are very high). In

addition, an intrauterine pregnancy with an IUD in place requires removal of the IUD, adding

some additional risk of miscarriage with removal. If the IUD is not removed, severe infection has

been reported in the second trimester.

Postpartum and post-abortion IUD use Both the TCu 380A and the LnG IUD are considered safe for placement immediately post partum and post abortion when no intrauterine infection is present. Although higher expulsion rates have been observed following postpartum and post second trimester abortion placement of

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

copper IUDs, expulsion rates are not higher following first trimester abortion (Grimes D. 2004). Data for the LnG IUD are not available, however because expulsion is probably the result of increased uterine irritability and contractility related to the delivery or the procedure one should expect the same.

For several decades the promise of expanding IUD uptake through immediate postpartum IUD services has lead to targeted interventions. Experience shows that the added burden during hospital based deliveries (particularly for good counseling and informed consent) predicts an increase during the introductory phase but a lack of sustainability. This appears to be true across all strata of maternity care infrastructures. Given the complexity of public sector maternity service delivery in poorer settings (in Africa the need to introduce PMTCT and the severe provider shortage), it is unlikely that postpartum IUD services will take hold broadly (Jacobson R- EngenderHealth 2006, Chirenge M- Zimbabwe 2006 , Somelela N- IPPF, 2006 personal communications). Postpartum IUD use is common in parts of China and Egypt where IUD use is high, and Mexico where it is moderate and obstetric care is institutionalized. Overall, adding counseling and IUD provision to a weak obstetric delivery setting is a formidable task and should only be attempted where quality monitoring can be implemented to assure informed consent.

Abortion services are provided on a random basis in almost all developing countries, influenced by laws for the most part. In those countries where abortion is legal, and therefore more available and organized in the public and private sectors post-abortion IUD placement is a safe option. Although described in the literature in the study setting, these publications describe outcomes of clinical trials that examine safety and efficacy (Grimes DA 2004). Published literature on programmatic implementation is scant, probably because model programs are rare.

Discontinuation of IUD use; clinical considerations

On a population basis, side effects are identified as the primary cause for discontinuation of use

of the IUD (See APPENDIX 2 for one-year discontinuation rates for 19 countries). These side

effects include irregular bleeding with both the copper bearing IUDs and the LnG IUD, and

increased menstrual bleeding with the copper bearing IUDs and amenorrhea with the LnG IUD.

However, removal rates due to bleeding pattern changes vary greatly among study populations.

A recent study from Scandinavia reported very low rates of discontinuation at 5 year follow-up

(2.1) (Pakarinen 2003) however other older studies that compare discontinuation with copper

IUDs report 5 year rates of 20% (Sivin I 1990, Andersson 1994). This may be a reflection of

different counseling practice rather than an inherent cultural problem.

One can assume that a certain amount of discontinuation is due to provider concern when these

normal side effects occur, and the lack of good training that would enable them to discern the

true need for removal, or adequate pre-insertion counseling to help the user discern in some

cases. Either way, this is an attendant risk with both the TCu 380A and the LnG IUD. Where

ultrasound or other diagnostics are unavailable the provider cannot differentiate between a lost

IUD vs. lost strings, bleeding from infection vs. a normally irregular bleeding pattern, or in the

case of a LnG IUD, method induced amenorrhea vs. intrauterine pregnancy or ectopic

pregnancy. In the case of Depo-Provera induced amenorrhea, which occurs in roughly 60 % of

users at 1 year, the short-term nature of the method and inability to "discontinue" at will has not

appeared to hamper uptake. Discontinuation rates at one year are high but reasons for this are not

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

clearly method related and could be access related. For long-term Depo-Provera users, it can

take up to a year to return to a regular menstrual pattern following discontinuation.

Table 3 represents six year interim results from a WHO sponsored multicenter trial designed to

compare the TCu 380A and the LnG IUD5.

Table 3. Cumulative net probabilities of IUD use discontinuation

(Standard error) per 100 women after six years of use (interim data to 30 September 2003)

Taken from WHO Annual Technical report 2003 Importance of the Continuation Rate The significance of discontinuation rates should not be underestimated. A simple calculation provides an idea of the impact of early discontinuation of a method. Note that most users are past postpartum amenorrhea and so are fully fecund, so unless users quickly adopt an alternative method, which many or most do not, they are exposed.

The available evidence shows the TCu 380A having a better continuation rate than that of the current LnG. That is not the only criterion for preferring one device over another, but it is an important one and we think points to the need to invest heavily in counseling and clinical training with the introduction of a hormonal IUD. When one device returns women to an exposed state for unwanted pregnancy sooner than another (and surely all IUD users wish to avoid pregnancy), there will be more unfortunate events than with the inferior device. Here is a simple exercise to illustrate that.

Assume a population of 100,000 women subject to an annual pregnancy rate of 300/1000 women. If the difference in mean continuation between the TCu 380A and the LnG were 3.5

5 We are still trying to confirm where the trial is ongoing but we don't believe that there is an African site,

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

years vs. 3.25 years, the results of the 3 months of extra exposure to pregnancy are shown in the

Table 4. If instead the difference were 3.5 years vs. 3.0 years, i.e. 6 months, the numbers would

double. The truth may be somewhere between, but the point is that the continuation rate is very

important. We do not know what the final, improved LnG device would do; hopefully it would

compete.

Table 4. The consequences of additional exposure to pregnancy as impacted by

continuation rates

difference difference

15,000 Extra pregnancies

5,000 Extra abortions if 1/3 of pregnancies are aborted

10,000 Extra births

100 Extra maternal deaths if the MMR is 1000/100,000 births

2,000 Extra infant deaths if the IMR is 200, or

2,500 Extra child deaths if the U5MR is 250

Plus Extra orphans in a high-HIV environment

Adapted from Ross 2006 Anemia: Could the LnG IUD have a public health impact?

Anemia is defined as a reduction below normal in the concentration of erythrocytes or hemoglobin in the blood; a normal hemoglobin (Hb) level in women is greater than 12 g/dl . Anemia occurs when the equilibrium is disturbed between blood loss (through bleeding or destruction) and blood production, which can be affected by a large number of factors. Iron deficiency anemia, one type of anemia, is caused by a lack of iron stores. Other nutritional deficiencies contribute to the range of anemias found in developing countries, but anemia is multifactoral and significant contributors include hookworm, malaria and other chronic diseases that affect either red blood cell survival or production. Blood loss, as a cause of anemia, is not listed in the developing country literature. Post-hemorrhagic anemia, caused by large amounts of blood loss due to an accident or an obstetric event is not listed because if the patient survives, the body should be able to replenish stores. Although hemorrhage is listed as the greatest cause of maternal death, it is the underlying anemia that tips the scale and leaves women without capacity to survive the loss of even normal blood loss associated with delivery, causing more than 60,000 deaths per year (UNICEF 2004).

Iron deficiency anemia is listed by WHO as one of the top ten most serious health problems. In adults iron deficiency affects the workforce with an estimated productivity loss of up to 2% of GDP in the worst countries. It not only increases the risk of a bad obstetrical outcome but contributes to the risk of prematurity, and low birth weight. Children born to iron deficient mothers start life with lower stores inherited from the mother and have difficulty catching up. They enter the critical period from age 6-24 months, when breast feeding supplementation begins, without ability to recover to build adequate iron supplies for health and normal cognitive and psycho-motor development, affecting approximately 40-60% of the developing world's children.

Documentation of anemia prevalence across Africa is poor and derived from small studies. The distribution of up to 80% in coastal regions and 30-40% inland reflects the multifactoral nature

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

of the problem given the impact of malaria, hookworm, and socioeconomic factors. Although about half of all cases are probably attributed to iron deficiency anemia a report in 2001 that looked at strategies to address iron deficiency anemia suggested that iron supplementation and micronutrient replacement is likely to have less impact than expected unless coupled with treatment for malaria and hookworm. It is also likely that the HIV epidemic is contributing more to this picture than ever before. (MacPhail 2001; OMNI 2006).

Why is all of this important? It is true that a medicated IUD such as the LnG IUD would decrease menstrual blood loss. In the woman who is child spacing one might argue that this saving would help to build iron stores that could make a next pregnancy safer for both mother and newborn. However, in light of the complexity of the anemia ‘puzzle" it remains unclear whether a decrease of menstrual blood loss and a potential marginal increase in hemoglobin in women who are child spacing would lead to lives saved.

In some countries where the uptake of Depo-Provera has been documented, the resulting amenorrhea provides a real time opportunity to look at any impact this might have on hemoglobin levels in select settings and should be further examined.

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

SECTION II

PROGRAMMATIC ISSUES

II.1 Estimating demand and potential demand in an expanded market

If, by asking about demand, we are asking whether there is some untapped interest out there in

adopting contraception, the answer is always yes. In every population there are at least some

women, and men, who do not want the next pregnancy. That is evidenced by the unmet need

figures, even though many women included in the "unmet need" category disagree and say they

will not use a method. However, they are roughly matched by other women who say they intend

to use a method, even though the surveys classify them as not having unmet need (this group is

mainly spacers who want a birth within two years but not right now).

In any case, unmet need does not serve well as a gauge of likely contraceptive adoption over the

next few years. In most countries, it is so large as to constitute an unrealistic outer limit of the

market. Prevalence of contraceptive use seldom rises more than one or two percent of couples

per year, and within that an individual method usually rises less. The global figure of 17% of

married women with unmet need (APPENDIX 3) will fall only gradually as prevalence rises,

and the grand total of 123 million women in need may even grow as populations increase.

As to "demand," in no country are women vocally "demanding" the IUD, but in all countries

there is at least some unexpressed potential for IUD use, and there is always a subgroup that

would use the method if it were readily available and presented effectively. "Market" is a more

useful concept than demand since it combines the element of programmatic push with the likely

response by the client. A stronger program combined with a more favorable setting makes for a

larger market. So to get a handle on the "potential demand", or likely increase in IUD use, we

need to consider the impact of strengthening a program along with the constraints of the setting.

That is, equally strong programs applied in all regions will yield less in sub-Saharan Africa than

elsewhere, but they will still yield something, and the yield will be greater where the program is

stronger.

Demand is heavily affected by the quality and reliability of the program as a whole over time,

which reflects the lack of resources in the setting. These lacking resources include: the absence

of providers altogether, not just that of trained providers; poor stability in the entire commodity

supply chain, not just that for IUD supply; and migration of public commodities into the private

sector (theft) for all re-salable commodities, etc.

Historical Experience for Increases in IUD Use

One fix on the probable market for increased uptake of the IUD is to look at the past record in

countries that have multiple surveys, to show the trends. Table 5 (page 29) details historical

experience for increases in IUD prevalence for 26 countries. These are countries where a clear

rise occurred, though the levels vary greatly, from very low in Nepal and Sri Lanka to very high

in Egypt and Uzbekistan. The annual pace of increase also varies, from lows of around 0.100

point to highs of around 1.000. That is, from a tenth of a point rise per year to a full point rise per

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

year. For example, in Iran, the rise over five years was from 7.0% to 8.3% of married women using the IUD, for an annual rise of 0.260 point per year. Across all countries the median rise is 0.506, a half point per year. Egypt is an outlier at 1.422 points per year over a long period. This gives rough bounds on what might be achieved in new national campaigns. The past IUD increases have of course occurred in the context of what total prevalence has done, which across all countries averages about 1.5 points per year, with an upper limit of around 2.5 points. A rise in IUD use can be partly due to substitution, with another method declining. For instance, in Egypt, pill use fell from 20% of women to only 9% during the IUD's steep climb. Or, the IUD rise can be accompanied by other increases, as in Tunisia, where pill use doubled from 5% to 11% while IUD use also rose. Figure 6 below shows the relationship between total prevalence and IUD prevalence. Figure 6a provides data based on 248 surveys taken since 1980, giving the two prevalence rates, and Figure 6b is based just on 114 surveys in the 26 countries with increases. In Figure 6a, there is a cluster at the extreme lower left for near zero values on both prevalence rates (as in sub-Saharan Africa), showing a direct relation for numerous countries. On the right side of the chart are the outliers, for which both figures are very high –IUD prevalence and total prevalence averaging around 65%. Figure 6b is similar, but without the cluster of near zero values at the lower left and with fewer points. IUD use has been an important determinant of total contraceptive use in many countries, and IUD use can be expected to rise at no more than about a point a year at the national level. Therefore, an optimistic scenario for selected sub-Saharan Africa countries would be a rise from about 3% now to 13% over 10 years. That would be a substantial contribution but it would require an intensive campaign with providers, resting upon the appeal of a new IUD device that promises health benefits. To be acceptable in a policy sense, it would have to be folded into the context of multiple method offerings. For a comparison, the injectable rose very rapidly in a few cases, but only moderately or not at all in other cases, as with the IUD. Peak cases are Indonesia (1.48 points/year from 1994 to 2002), and Namibia (1.37 points/year from 1992 to 2000).

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Figure 6. Relation of Total Prevalence to IUD Prevalence

Figure 6a. Total prevalence follows IUD prevalence

(248 national surveys)

Prevalen

Figure 6b. Total prevalence follows IUD prevalence in countries having past IUD increases

(114 national surveys)

Prevalen

(Source: Macro DHS StatCompiler)

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Table 5. Historical Experience for Increases in IUD Prevalence

LATIN

AMERICA

MIDDLE EAST

SUB-SAHARAN

AFRICA

CENTRAL

ASIAN REP.

*Percent of married women aged 15-49 using the IUD **Read: Iran's IUD prevalence rose by 0.260 point per year From 1992 to 1997, that is, from 7.0% to 8.3%. (Source: Macro DHS StatCompiler)

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Projections for Users and Adopters: Examining the numbers

The historical experience just outlined affords one gauge of the IUD market; repeat surveys show

that a working maximum is an increase of 1% per year in the proportion of married women using

the IUD. If we take the median value, which happens to be half of that (0.5%), as a basis for

illustrative projections, we can estimate the number of new adoptions per year per country, as in

Table 6 below. A range around each number is readily obtained -- simply take half of each

number to represent one-fourth percent rise per year (0.25%), or add half to the number to

represent three-fourths percent rise per year (0.75%). If there is an interest in exploring a full one

percent rise per year, double the number of adopters. (All this could be shown as alternative

projections but the table below would become cumbersome.)

Table 6 shows first the IUD prevalence in the latest survey, with regional averages based upon

aggregated numbers of users and women in the countries. The second column shows what IUD

prevalence would be five years later, by adding a half percent per year (2.5% in 5 years). The

next two columns give the numbers of married women and users, with users calculated as

prevalence multiplied by women. The next to last column gives the estimated numbers of IUD

adoptions needed to match the prevalence increase. There are three components to the adopters

needed: (a) a half percent of married women to raise prevalence by the assumed amount, (b)

adoptions to replace last year's dropouts from terminations, aging out, etc. (33% of last year's

users), and (c) a 2% increase to allow for population growth. The final column compares

adoptions to women to get the annual acceptance rate. (The top figure, for all less developed

regions, is 6%, but that is for annual adoptions, not the net annual rise in prevalence of one-half

percent per year. The difference is due to the three components just explained.)

Countries and regions differ sharply in their adoption rates because adoptions depend heavily

upon the numbers required to replace last year's IUD dropouts. The assumed mean continuation

period of 3.5 years (for the TCu 380A) implies the reciprocal, an annual loss from the using pool

of 28%, and about 5% more who age out or end their marriage, for 33% total. Where users are

numerous, as in high prevalence areas, dropouts are also numerous, driving up the adopters

needed to maintain prevalence, quite apart from raising it. So adoption rates must be high where

IUD prevalence is high to maintain this equilibrium. Both are maintained at a very low level in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Each regional figure reflects the dominance of particular countries. East Asia's figures reflect

China's high IUD use, whereas South America's figures reflect Brazil's very low use. Applying

the assumed prevalence increase of a half percent to every country is crude of course, but the

exercise yields the aggregate picture, with proper country weights by population, and it gives a

useful order of magnitude. As noted above any total can be lowered or raised to assume an

annual increase of a fourth percent or three-fourths percent, etc. Higher adoption rates have

occurred in special projects, but national changes usually come about slowly. (The full table is in

APPENDIX 4).

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

Table 6. Projections of IUD prevalence, users, and adopters at a half percent rise per year

in IUD prevalence

Adoption

Rate (% of

Prevalence

after 5 yrs at

Adoptions

latest survey

1/2% rise/yr

MWRA in 2005

Users in 2005

during 2006

LESS DEVELOPED

REGIONS

941,040,280

145,843,807

56,625,597

Sub-Saharan Africa

Central Asia Rep.

N. Africa/Middle East

Caucasus

Latin American & Caribbean

(Source: Appendix 4).

Intention to Use the IUD

Respondents in DHS surveys who are not using a method are asked whether they intend to do so,

and if so what method they would prefer. Rather dramatic patterns appear across some 140

surveys when preference for the IUD is compared to the preference for the competing methods

of pill and injectable (re-supply) or sterilization (long-term), all by region. (APPENDIX 5 shows

only the most recent survey for each country.)

Briefly, the patterns exactly parallel the use patterns. Hardly anyone in sub-Saharan Africa

names the IUD, but many do so in the Middle East. The injectable is popular in sub-Saharan

Africa, with a remarkable uniformity across the many countries. The injectable is decidedly

unpopular (or less known) in the Middle East. In Latin America, it and the IUD are sometimes

high and sometimes low. Sterilization is unpopular in the Middle East but very popular in Latin

America. The pill is popular everywhere.

Geographically, the highly disparate pattern of method choice is as notable for future intentions

as it is for current use, and it might remain so if nothing were to change. However, both use and

intentions are amenable to change, as evidenced by the increased uptake of the injectable,

although that is a much different kind of method and it reflected major exertions by public or

private sector forces. In much of sub-Saharan Africa the injectable has been on the rise. From

1990-1994, UNFPA shipments of progestin-only injectables increased from 4.5 million to 16.7

million doses. USAID began providing supplies in 1992 to other countries. In some countries,

such as Nepal, the injectable is supplied in pharmacies (Finger WR 1995). Myths about the

injectable's impact on fertility were barriers at first; however it appears that efforts directed to

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross

overcome those have succeeded in many places and the ease of administration has probably aided the continued rise in uptake.

II.2 Current strategies for an IUD revitalization

A critical question is whether a new IUD would be additive or a partial replacement? To address

this question it is important to think through a strategy of expanded IUD use beyond the above

calculations for a gradual increase in uptake balanced by annual discontinuations. First, consider

a favorable opportunity for expansion, where the setting has a proven track record for delivery of

services and the program, weak or strong, has demonstrated some commitment to the IUD. In

that case, we can assume that there would be both an addition and some replacement to use of

the TCu 380A, assuming that all other programmatic conditions were equal, such as cost and

supply of the new IUD. But in cases where the setting is weak and hard to impact through a

"vertical" introduction of a new IUD, any contribution of a new IUD would seem to be additive,

assuming a vigorous provider initiative. In sub-Saharan Africa, if a new IUD were introduced

and marketed as an improved method with clinical advantages it might migrate to the private

sector first, leaving the TCU 380A in the public sector. This is of course hypothetical. Past

experience with the introduction of new methods, such as NORPLANT, cannot be used to

inform this equation because the LnG IUD, although new, is still an IUD and has the attendant

associations and programmatic constraints. In any case, three strategy options follow.

Strategy Option No. 1. An increase in IUD use is most likely in countries where the method is

already established, where its own prevalence is neither too low nor too high, and where total

prevalence is neither too low nor too high. The reasoning is that prospects are unfavorable if the

IUD has not taken hold after all these years, or where total prevalence has not started to rise

(D.R. Congo, etc.). Equally, if IUD or total prevalence is already very high, additional rises are

improbable.

Therefore, the matrix in Table 7 (page 34) isolates countries where both IUD and total

prevalence are intermediate. They fall in the middle cells, with the 21 countries shown in bold.

These deserve special consideration as the most promising sites.

However, the "middle-middle" strategy is only a starting point, and it cannot be the only guide.

No country in sub-Saharan Africa makes the cut, and the only very large country included is

Indonesia, so even if IUD use increases by a half point of prevalence a year in the 21 countries,

there would be only a modest change for the developing world as a whole. Some of the other

giants fall into the very low cells for either IUD prevalence or total prevalence or both. It is

tempting to add at least a few large countries from the less favorable cells, and that is proposed

in the following strategy.

Strategy Option No. 2. USAID is supporting an IUD revitalization effort (Acquire Project) that

identifies eight sub-Saharan countries for special attention. These all fall into the last column and

bottom two rows of Table 7 below (underlined). IUD use has not yet taken hold in these

countries (although it was previously used more in Kenya than it is now). The large countries of

Nigeria and Ethiopia are included, and three in East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania),

where conditions are somewhat more favorable. Ghana is also included, along with Mali and

Guinea. These choices necessarily reflected a blend of Mission interest, central priorities, and

IUDs in Developing Countries-Perkin, Pollack and Ross