Kamagra gibt es auch als Kautabletten, die sich schneller auflösen als normale Pillen. Manche Patienten empfinden das als angenehmer. Wer sich informieren will, findet Hinweise unter kamagra kautabletten.

Doctorhuff.net

Practice Management and Human Relations

Ethical decision-making for multiple

prescription dentistry

Kevin Huff, DDS, MAGD n Marlene Huff, PhD, RN n Constantin Farah, DDS, MSD

Technology provides a selection of treatment choices for dental

This article presents four case studies that illustrate the process of

problems. Dental ethics must be applied to the development of a

ethical decision-making for the appropriate treatment.

treatment plan and the selection of methods. Treatment options

Received: August 2, 2007

should consider the patient's circumstances and desires as well

Accepted: September 19, 2007

as the dentist's decision as it relates to best practices in dentistry.

The art and science of dentistry a given patient may be different for mendations. The American Dental

has progressed very rapidly

the same patient at different times

Association's Code of Ethics lays

since the introduction of the

in his or her life.

the groundwork; how the Code is

high-speed handpiece in the 1950s.1

Recognizing the importance of

applied reflects the dentist's indi-

There has been a paradigm shift

optimal oral health, coupled with

vidual values (see the table).3

from paternalistic management

the rapid advancements in technol-

It often is possible to achieve

of obvious problems to a medical

ogy, may lead the practitioner to

similar results from the application

model of dental care, which includes

be overzealous in treatment. A

of different approaches to treatment

prevention and management

comprehensive plan of care that is

or prevention.4 Having multiple

of dental disease and prosthetic

appropriate for the patient should

options leads to what Sadowsky

rehabilitation to restore normal

include the application of ethical

cal ed the "moral dilemma of the

oral function. Discovery of the

principles in the development,

multiple prescription in dentistry."5

relationship between oral health and

acceptance, and implementation of

One approach may be considered

systemic disease has raised awareness

treatment. The science of dentistry

more beneficial than another at

concerning the importance of oral

makes it possible to offer multiple

a given time. The options that a

health. In 2000, the U.S. Surgeon

options to patients; however, the

dentist offers and a patient selects

General cited oral health as a major

art of dentistry includes the need

can be influenced by changes in the

concern.2 Advancements in tech-

to communicate with the patient

patient's lifestyle or physical condi-

nology offer a variety of solutions

and to apply ethical principles

tion or a change in terms of available

for managing similar dental situa-

when making treatment recom-

treatment methods. The clinician

tions and it is incumbent upon each

practitioner, as a member of an ethi-

cal profession, to educate patients

about their appropriate treatment

Table. Ethical principles.3

options, allowing them to make

autonomous treatment choices that

are in their best interest.

Patient autonomy ("self-governance")

The dentist has a duty to respect the patient's

It generally is understood that

rights to self-determination and confidentiality

many treatment options are avail-

Nonmaleficence ("do no harm")

The dentist has a duty to refrain from harming

able for any given dental condition.

A definite decision-making process

Beneficence ("do good")

The dentist has a duty to promote the patient's

helps to determine the appropriate-

ness of each treatment modality. It

Justice ("fairness")

The dentist has a duty to treat people fairly

also must be acknowledged that the

Veracity ("truthfulness")

The dentist has a duty to communicate truthful y

ethically appropriate treatment for

538 September/October 2008 General Dentistry www.agd.org

should share his or her reasons

col to matters of human concern.

Informed consent is an important

for recommending one treatment

Normative ethics refers to an area

component of decision-making;

option over another; however, other

of inquiry that investigates right or

however, sharing all of the details

reasonable treatment options should

wrong conduct, looking at ethical

about a case may complicate the

be presented as well. An ethical

principles and rules commonly

process. The dentist must decide

decision-making process is necessary

associated with the situation and

how much information to share

when discussing the risks and ben-

assessing duties and obligations.

with the patient. For example, fair

efits for the patient and arriving at an

Autonomy includes self-determi-

fee structures are included in the

appropriate decision for treatment.

nation, confidentiality, and the right

principle of veracity; misrepresenta-

Professional responsibility includes

to select and/or to refuse treatment.

tion is considered to be untruthful.

acting in a manner that promotes

The dentist must inform the patient

Beneficence and nonmaleficence

"good" for the patient. Ethical prin-

of all reasonable and appropriate

include benefits versus harm. Com-

ciples should be the underpinning

treatment options. This way, the

bined, this dichotomy is a utilitarian

for the plan of care and should affect

patient is actively involved in treat-

principle that includes acting in a

al choices made concerning care

ment decisions. Dentists serve not

manner that promotes the good

only as diagnosticians but also as

of the patient. Even though a

Dentistry is a moral profession,

educators. Trust may be weakened

particular technique could address

guided by normative principles.4

if dentists limit the amount of infor-

an immediate problem, the overall

As a result, dentists are obligated

mation patients receive.

effect may harm the patient in a way

to choose a course of treatment

Too much information also can

that is not immediately apparent.

that allows them to be "caring

present a problem.9 The dentist

Weinstein has proposed a process

and fair in their contact with

must use good judgment when

for making ethical decisions for

patients."3 Although increased

obtaining informed consent.

patient care. This process involves

commercialism may be difficult to

Education may inform patients as

gathering relevant facts, including

avoid, patient autonomy should

to what they need but that may

medical history and social factors,

be the overwhelming decision-

not be what they want. Autonomy

ascertaining possible treatment

making principle. Preservation

involves decision-making from both

options, and answering questions

of the profession of dentistry and

the patient and the dentist. The

concerning what course of treat-

the self-policing autonomy that it

right to refuse treatment is inherent

ment should be followed and why.7

enjoys necessitates adherence to the

in the principle of autonomy.10

The first step involves gathering

normative picture.7 Members of the

Justice includes trust and kind-

all of the relevant facts, including

dental profession and of the com-

ness. Trust is built upon being

medical history, dental history, and

munity at large expect dentists to

honest; patients trust that dentists

social factors. Relevant ethical prin-

act ethically, according to a balance

have a current working knowledge

ciples are identified and a decision

of certain norms: nonmaleficence,

of modern dental techniques. As a

is made regarding conflicts. For

beneficence, justice, veracity, and

result, continuing education is an

example, when a patient requests

respect for patient autonomy.3 The

ethical obligation of the dental pro-

a treatment that would knowingly

personal virtues of the dentist and

fession (one which may or may not

render his or her condition more

the intrinsic values of the profession,

be required by law). If the patient

unstable or uncertain than at the

the patient, and society must be

requires treatment that is beyond

time of the initial visit, the personal

considered when choosing appropri-

the skill of the primary dentist,

virtues of the dentist and the

ate treatment for any given situation

it is expected that the dentist will

principles of nonmaleficence may

(see the table).3

refer the patient to more qualified

conflict with the need to respect the

Codes of ethics describe expected

clinicians. Ethical decision-making

patient's autonomy.

standards of behavior for self-

reduces the tendency toward over-

Next, all of the treatment options

policing professions (dentistry,

treatment; that is, a dentist should

available for the given situation

medicine, nursing, and so forth).

not perform a procedure that is

should be ascertained (for example,

Ethics also may be considered a

not indicated simply to please the

a Class II carious lesion may be

mode of inquiry for processing the

treated with an interim glass

moral dimensions of an issue.8 To

Veracity includes judgment

ionomer restoration, an interim

engage in ethics is to apply a proto-

concerning what to tell the patient.

zinc oxide/eugenol restoration,

www.agd.org General Dentistry September/October 2008 539

Practice Management and Human Relations Ethical decision-making

a composite resin restoration, an

amalgam restoration, a porcelain

inlay, a resin inlay, or a gold inlay).

Finally, the dentist selects the

appropriate treatment option by

answering the questions "What

should be done?" and "Why should

it be done?" Although it is inherent

in the process, perhaps a fourth

step should be added: to arrive at a

treatment option that is acceptable

to both the patient and the dentist.

Autonomy, or the patient's decision

about treatment, is an important

This article presents four case

reports that illustrate how ethical

Fig. 1. A 45-year-old woman with a loose maxil ary anterior FPD from teeth No. 6–9.

principles were applied in the deci-

sion-making process to determine

the most appropriate treatment.

The authors acknowledge that the

treatment rendered is not consid-

ered to be ideal in these situations

according to accepted standards.

However, in each case, ideal treat-

ment options were presented as part

of the informed consent process.

Weinstein's model was used to guide

Case report No. 1

A 45-year-old woman sought treat-

ment for a failing four-unit fixed

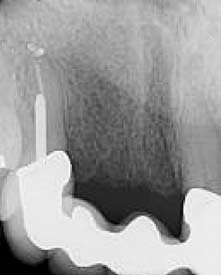

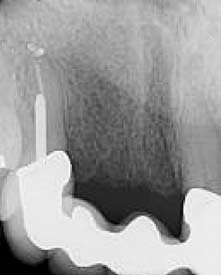

Fig. 2. A radiograph and occlusal view of the patient, indicating the recurrent caries that caused

partial denture (FPD) that had

the existing FPD abutment to fail. The cavosurface of the healthy tooth after excavation is at the

been placed more than ten years

osseous crest.

earlier (from teeth No. 6–9). She

had recurring dental caries under

the distal abutment crown that

was inaccessible for repair without

removing the FPD (Fig. 1). The

contraindication to dental surgery.

lengthening surgery, individual

right maxillary canine abutment

The patient wanted to receive the

abutment crown therapy for teeth

was mobile and fractured at the

least costly restoration as quickly as

No. 6 and 9, and removable partial

gingival margin (Fig. 2); in addi-

possible. The function, esthetics,

denture (RPD) therapy. A second

tion, the patient had an Angle's

and durability of her previous FPD

option involved the aforementioned

Class I occlusion with stable centric

were acceptable to her. She was

endodontic therapy and crown-

occlusion and anterior guidance.

opposed to any type of removable

lengthening surgery plus FPD

The patient had received a nine-

therapy, utilizing teeth No. 6 and 9

unit, four implant-supported FPD

Based on the patient's wishes, three

as abutments. A third option would

(from teeth No. 19–27) more

treatment options were available.

involve extracting the right canine

than a year earlier; it was in good

One option involved endodontic

and placing implants in the sites of

condition. Medically, there was no

therapy on the right canine, crown-

teeth No. 6 and 8, with an implant-

540 September/October 2008 General Dentistry www.agd.org

that have improved the feasibility of

fixed prostheses and in an era that

places a high value on esthetics.

The costs associated with complex

restoration of severely compromised

teeth, the associated morbidity,

and the unfavorable comparative

prognoses suggest a need to consider

utilizing dental implant therapy

and/or FPD therapy as alternatives.

The decision should be based on the

Fig. 3. The patient in Figure 2 after receiving appropriate endodontic therapy and phased FPD

patient's medical history and socio-

therapy. Note the favorable tissue response and esthetic appearance created by wel -developed

economic status, as well as proper

ethical principles.

Ethical considerations

Autonomy

The patient was presented with all

supported FPD and an independent

and a full-coverage restoration

possible treatment options, includ-

crown on tooth No. 9. After thor-

subsequent to endodontic therapy.

ing the option to do nothing with

ough discussion, the patient chose

For adequate retention, it generally

her failing FPD. As with all of the

the second of the three plans.

is understood that the final crown

cases presented in this article, the

The existing FPD was removed,

margin should be at least 2.0 mm

patient was well-educated through

endodontic therapy was completed

apical to the cavosurface margin of

discussion and commercially

on tooth No. 6, and a pre-fabricated

the core, creating a ferrule. This

prepared video presentations. In

post and a bonded resin core were

complex approach to restoration is

addition, she had received implant

placed. A provisional FPD was

technique-sensitive and the progno-

therapy on her mandibular arch

fabricated and crown-lengthening

sis for the tooth as an abutment for

previously without complication.

surgery was completed from teeth

No. 6–11. After ten weeks of tissue

For healthy biologic width, there

healing, a porcelain-fused-to-high

must be adequate space between the

The patient had been treated previ-

noble metal FPD was fabricated

crown margin and the crestal bone.

ously with a very functional and

and luted with resin-reinforced glass

Osseous crown-lengthening surgery

esthetic FPD. FPD therapy has

ionomer cement (Fig. 3).

is indicated when coronal tooth

been utilized for many years in

The patient had enjoyed acceptable

structure loss is significant enough to

conventional dentistry and there

success with her previous four-

compromise the biologic width when

was no absolute contraindication

unit FPD and understood that an

an ideal restoration is placed. This

for FPD therapy, since the abut-

implant-supported prosthesis would

procedure is a subtractive approach

ment teeth were prepared and

provide the best longevity and that

that requires removing bone in an

would have required crown therapy

crown-lengthening surgery is a sub-

era when efforts are conscientiously

regardless of the therapy selected.

tractive therapy rather than additive.

being made to provide additive treat-

The risks of crown-lengthening

ments that regenerate bone.

surgery (and the fact that bone

Dental considerations of

When a tooth is severely com-

would need to be removed) were

promised, an alternative to the

discussed thoroughly. The patient

Periodontally sound teeth that

aforementioned therapy would be

clearly understood her condition

have endured severe structural

to extract the tooth and replace it

and made an educated choice. The

loss (that is, more than 50% of

with either an RPD or an implant-

same clinicians who completed the

the coronal tooth structure) and

supported prosthesis. Although

previous implant therapy and pros-

still are deemed restorable usually

RPDs once were common practice,

thesis presented and performed this

require either a prefabricated or

they have fallen out of favor in light

particular treatment, so the patient

laboratory-made post and core

of modern materials and techniques

was not subjected to outside bias.

www.agd.org General Dentistry September/October 2008 541

Practice Management and Human Relations Ethical decision-making

Fig. 5. The patient in Figure 4, after receiving a zirconia-based FPD that replicated the original

Fig. 4. An anterior view and a radiograph of a 64-year-old woman with failing restorations on her

position of the natural dentition in accordance

central incisors.

with the patient's esthetic demands.

a stable, esthetic solution for her in

options were considered. The first

Although it may be argued that

accordance with her chief concerns.

option involved endodontic retreat-

crown-lengthening surgery removes

ment, bonded resin cores, and crown

bone, it also would allow the

Case report No. 2

therapy on teeth No. 8 and 9. The

dentist to save the canine. Since all

A 64-year-old woman sought treat-

second option involved extracting

procedures were performed accord-

ment for failing restorations of her

teeth No. 8 and 9, fol owed by

ing to accepted protocols (with

maxillary central incisors (teeth No.

phased FPD therapy. The third

2.5 mm of ferrule for abutment

8 and 9). External root resorption

option involved extracting teeth No.

retention on tooth No. 6, while the

was evident (Fig. 4). The patient

8 and 9, followed by phased remov-

abutment teeth had been prepared

had an Angle's Class II Division

able denture therapy. The fourth

as abutments previously), no harm

II occlusion and a moderate shift

option involved extraction of teeth

was caused to the patient. Healing

from centric occlusion to maximum

No. 8 and 9, fol owed by implant

discomfort and surgical involvement

intercuspal position without pain.

replacement therapy for teeth No. 8

were similar to what would have

There was steep anterior guidance

and 9 and implant-supported crowns.

resulted from implant therapy.

and a high maxillary lip attachment.

The patient selected extraction

The patient was in good health with

and the FPD. Once that decision

a history of seasonal sinusitis and

was made, teeth No. 8 and 9 were

The benefits of implant therapy

was not taking any medications on

extracted and the maxil ary lateral

were superseded by the patient's

a regular basis. Her dental history

incisors were prepared for abutment

concerns about the short-term cost

included multiple minimally accept-

crowns. Synthetic ridge preservation

of therapy. A plan for failure was

able alloy and resin restorations.

material (Bioplant, Kerr Dental,

discussed with the patient, who

More than 40 years earlier, the

Orange, CA; 800.537.7123) was

clearly understood that the lifespan

patient had received endodontic

placed according to standard proto-

of the FPD was expected to be

therapy on teeth No. 8 and 9; this

col and a provisional FPD was fab-

shorter than that of an implant-

therapy was followed by the placing

ricated to al ow for adequate tissue

supported prosthesis. The patient

of porcelain veneers that had been

maturation. The preparations on

understood that failure could

repaired multiple times. She had a

the lateral incisors were refined and a

require either a removable prosthesis

history of sporadic recall visits and

four-unit zirconia-substructure FPD

or a more costly implant-supported

poor oral hygiene. The patient said

(Lava, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN;

prosthesis. The patient benefited

that she wanted "whiter" incisors

888.364.3577) was fabricated for

from crown-lengthening, endodon-

but she did not want the position or

teeth No. 7–10. The FPD was luted

tic therapy, and conventional FPD

shape of her teeth to change.

with resin-reinforced glass ionomer

therapy because this plan provided

Given these factors, four treatment

cement (Fig. 5).

542 September/October 2008 General Dentistry www.agd.org

understood that the lifespan of an

FPD therapy has been utilized in

FPD most likely would be shorter

conventional dentistry for many

than that of an implant-supported

years, with predictable outcomes.

prosthesis. The patient understood

No absolute contraindication

that in the event of failure, her

for FPD therapy exists in this

only choices of therapy might be

particular case, although it would

a removable or implant-supported

require altering the abutment teeth.

prosthesis. The patient benefited

However, when the patient's desired

from phased FPD therapy in this

esthetic outcome was considered

case because it was the most predict-

carefully, there were reasonable

able treatment option for meeting

contraindications for an implant-

her demands and expectations.

retained prosthesis or RPD therapy.

The dentist and patient had a frank

Case report No. 3

Fig. 6. A radiograph of a 62-year-old man with

discussion about the difficulties that

A 62-year-old man had a failing

a failing cantilever FPD. No photograph was

would be encountered in meeting

cantilevered FPD that replaced the

the patient's esthetic demands

left maxillary central incisor (Fig.

and the expected results of each

6). Tooth No. 8, the single abut-

treatment option were reviewed.

ment, was mobile and elicited pain

The patient clearly understood her

on percussion. An Angle's Class I

condition and made an educated

occlusion existed with stable centric

The prognosis of re-restoring teeth

choice. No guarantees or promises

occlusion and anterior guidance.

No. 8 and 9 was guarded due to the

were made. It was made clear to

The patient had a history of acid

lack of substantial remaining root

the patient that her home compli-

reflux, asthma, chronic sinusitis,

structure and external root resorp-

ance would determine the success

primary tension headaches, and

tion. The patient's esthetic demands

of any treatment option and the

arthritis; his current medications

and existing anatomy created a

relative fees for each treatment

included Prilosec (AstraZeneca,

contraindication for RPD therapy.

option were discussed openly and

Westborough, MA; 800.236.9933)

It was unclear whether the patient

and lactase. The patient had a his-

would be satisfied with implant

tory of excellent oral hygiene and

therapy due to the uncertain gin-

compliance with recommended

gival esthetic outcome, which cur-

Since all procedures were performed

dental treatment. Seven years

rently is a risk factor for implants in

according to accepted protocols

earlier, the same dentist had placed a

the esthetic zone. Since the patient

and because the patient was clearly

crown that was not esthetic on tooth

desired an exact duplication of the

informed about all procedures prior

No. 7. Since the patient was an

crowding of her original anterior

to treatment initiation, no harm

optometrist and had direct and close

teeth, an FPD was considered to be

was caused to the patient. Healing

personal contact with the public, he

the best course of therapy.

discomfort and surgical involvement

did not want any long-term remov-

were within normal limits.

able prostheses; he also was opposed

to further tooth reduction unless it

was absolutely necessary.

The patient was presented with

Since the patient's home hygiene

Three treatment options were con-

all reasonable treatment options,

practices were questionable, the

sidered. The first option involved

including the option to do nothing

success of dental implant therapy

endodontic therapy, with a new

with her existing dentition. She

was uncertain. The potential need

crown for tooth No. 8 and a single-

was made aware of the anticipated

for future extraction might require a

tooth RPD. The second option

difficulty of fabricating a prosthesis

multi-tooth RPD; the design of such

involved performing endodontic

that would comply completely with

a prosthesis might be complicated

therapy on tooth No. 8 and conven-

her esthetic demands. The patient's

by endosseal implants in the sites of

tional FPD therapy from teeth No.

desire to recreate her existing maloc-

teeth No. 8 and 9. A plan for failure

8–10, replacing tooth No. 9 with a

clusion was honored.

was discussed with the patient, who

pontic. The third option involved

www.agd.org General Dentistry September/October 2008 543

Practice Management and Human Relations Ethical decision-making

Fig. 7. The patient in Figure 6, after receiving dental implants and an

Fig. 8. The patient in Figure 6, after splinted, implant-supported crowns

interim acrylic RPD. The existing crown on tooth No. 7 was made to

were fabricated to replace teeth No. 8 and 9. The crown on tooth No. 7

match the existing cantilever FPD.

was replaced to provide a more esthetic result.

extracting tooth No. 8 and utilizing

nothing with his existing dentition.

were within normal limits. An

implant therapy to replace teeth No.

He was made thoroughly aware of

interim RPD was fabricated during

8 and 9. The patient selected the

the difficulty of providing a prosthe-

the healing period so that the patient

third option; in addition, he wished

sis that complied with his esthetic

did not have to endure social stigma

to replace the crown on tooth No. 7

demands. The dentist exercised

due to missing central incisors.

with a more esthetic restoration.

professional autonomy by replacing

Once a treatment plan was

the restoration on the lateral incisor

selected, tooth No. 8 was extracted

at no fee because he was not satis-

Considerations for the patient's

and bovine bone was grafted for

fied with the result of his previous

profession and psychosocial success

ridge preservation. Two endosseous

solidified the selection of implant

dental implants were placed and

therapy over other treatment alter-

an interim acrylic RPD (with no

natives. This treatment choice cre-

contact over the implant sites) was

There was no absolute contraindica-

ated a situation that was more stable

fabricated for esthetic function

tion for FPD therapy but there

and predictable than his original

only (Fig. 7). Definitive implant-

were relative contraindications for

prosthesis. The dentist's decision

supported crowns were fabricated

an implant-retained or removable

to replace the restoration on tooth

to replace teeth No. 8 and 9 and the

prosthesis. The patient was given

No. 7 at no fee was made with the

crown on tooth No. 7 was replaced

the same options for treating his

patient's best interest in mind.

(Fig. 8). The restorability of tooth

condition as anyone else would have

No. 8 was questionable and tooth

received in a similar situation. He

Case report No. 4

No.10 was virgin. Because of the

also was clearly informed that his

On two different occasions (two

patient's profession and his desire

home compliance would determine

years apart), a 62-year-old woman

to avoid a removable prosthesis, a

the success of any treatment option.

sought treatment for maxillary

definitive RPD was contraindicated.

incisors that had fractured 2.0 mm

The crown on tooth No. 7 was

coronal to the free gingival margin.

replaced at no fee to the patient.

Since al procedures were performed

Tooth No. 7 was the first to fracture

according to accepted protocols

(Fig. 9); tooth No. 10 fractured two

Ethical considerations

and because the patient was clearly

years later (Fig. 10). An Angle's

informed about al procedures prior

Class I second premolar bilateral

The patient was presented with

to treatment initiation, no harm

occlusion had been restored previ-

all possible treatment options,

was caused to the patient. Healing

ously, with stable centric occlusion

including the option to do

discomfort and surgical involvement

and adequate anterior guidance.

544 September/October 2008 General Dentistry www.agd.org

therapy to replace tooth No. 20

without incident.

The first treatment option

involved endodontic therapy on

the involved lateral incisor, crown-

lengthening surgery, fabrication of

a post and core, and crown therapy.

The second option involved extrac-

tion of the fractured lateral incisor

and phased FPD therapy, utilizing

the lateral canine and central inci-

sor as abutments. The third option

involved extracting the fractured

Fig. 9. A radiograph and anterior view of a 62-year-old woman with a fracture just above the

lateral incisor and utilizing an

gingival margin on tooth No. 7.

RPD. The fourth option involved

extracting the incisor and utiliz-

ing implant replacement therapy,

replacing the lateral incisor with an

implant-supported crown.

Crown-lengthening therapy would

alter the gingival profile significantly

and expose the margins of the exist-

ing adjacent crowns. FPD therapy

was contraindicated at both visits

due to the cost already invested in

crown therapy on adjacent teeth.

Implant therapy appeared to be the

best treatment option.

Although the patient was given the

same four treatment options at both

Fig. 10. A radiograph of the patient in Figure

Fig. 11. A radiograph of the patient in Figure

visits, she made a different choice

9 taken two years later demonstrates a similar

9, after receiving a dental implant to replace

each time. At her first visit, the

fracture on tooth No. 10.

tooth No. 7 while the gingival architecture was

patient requested implant replace-

ment therapy because she had been

pleased with the results of previous

implant therapy. At the second visit,

the patient's situation had changed

and she was concerned about under-

The patient had a history of fibro-

Inc.), Oxycontin (Purdue Pharma,

going any additional surgery, leading

myalgia, osteoarthritis, hypothy-

Stamford, CT; 800.877.5666),

her to choose the first option.

roidism, sleep apnea, hypertension,

and aspirin with calcium. A his-

Tooth No. 7 (the first fractured

depression, anxiety, chronic sinus-

tory of excellent home care and

tooth) was extracted atraumatically

itis, and primary tension head-

compliance with dental therapy

and an endosseous implant was

aches. At the time of both visits,

was obvious upon the initial visit,

placed immediately at the time of

she was taking Prinivil (Merck &

but declining health and dexterity

extraction. The patient declined to

Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ;

became evident by the time of

receive a provisional restoration. An

800.444.2080), Zoloft (Pfizer, Inc.,

the next visit two years later. The

implant-supported crown was fabri-

New York, NY; 800.223.0182),

patient was pleased with her smile

cated (Fig. 11). When tooth No. 10

Xanax (Pfizer Inc.), Levoxyl (King

and did not wish to alter her gin-

fractured similarly two years later,

Pharmaceuticals, Bristol, TN;

gival profile; she had been treated

endodontic therapy was completed,

800.776.3637), Neurontin (Pfizer,

previously with dental implant

a prefabricated post and resin core

www.agd.org General Dentistry September/October 2008 545

Practice Management and Human Relations Ethical decision-making

Fig. 12. A radiograph of the patient in Figure 9, after conven-

Fig. 13. An anterior view of the patient in Figure 9, after receiving a conventional

tional therapy was completed to restore tooth No. 10. An ideal

crown supported by a prefabricated post and core on tooth No. 10. The gingival

ferrule was sacrificed to preserve biologic width.

architecture was maintained.

was placed (Fig. 12), and the tooth

treatment option. She declined

the best possible prognosis, based on

was restored using a porcelain-

crown-lengthening surgery with

the patient's prior experience with

fused-to-high noble metal crown

the thorough understanding that it

dental care and the fact that remov-

without osseous crown-lengthening

may be necessary in the future for

ing the adjacent crowns to fabricate

surgery. (The biologic width viola-

optimal gingival health.

an FPD would subject those teeth

tion was minimized to the greatest

to unnecessary trauma and lead to

extent possible.) The patient's

additional expense. By the time

esthetic and functional needs were

All reasonable treatment options

the patient sought treatment for

met appropriately with two different

were presented to the patient. Her

tooth No. 10, it was apparent that

approaches to care (Fig. 13).

medical history, desires, and capa-

elective surgical procedures should

bilities were considered carefully

be avoided due to medical risks.

Ethical considerations

and independently at the time of

Therefore, the patient's health at the

each presentation.

time of each event was factored into

In both scenarios, the patient was

the selection of a treatment modal-

presented with all possible treatment

ity for each situation.

options, including the option to do

Although the "ideal" protocol was

nothing with her existing dentition.

not followed in the restoration of

She was made aware of the difficulty

tooth No. 10, the patient was clearly

In each of these case reports, ethical

that would result from crown-

informed about al procedures prior

principles guided the plan of care.

lengthening therapy. At her first

to treatment initiation and no harm

Patient autonomy was the last step

visit, she was predisposed to dental

was caused to her. Healing discom-

in the ethical decision-making pro-

implant therapy because of suc-

fort and surgical involvement were

cess. The dentist used knowledge

cessful previous implant therapy; at

within normal limits. The patient's

and ability to answer the questions

that time, she declined a provisional

request for the course of therapy in

regarding why treatment was neces-

prosthesis to reduce the cost of ther-

both scenarios was reasonable.

sary, enabling the patient to make

apy. By the time of the second visit,

a sound autonomous decision. The

she was aware of the decline in her

principle of veracity was not noted

health and was willing to accept the

Initially, implant therapy appeared

for each case because it is a value of

risks of a somewhat compromised

to be the best treatment option with

the authors to tell the truth about

546 September/October 2008 General Dentistry www.agd.org

treatment options within the limits

tion of technological advances in

of the information that is available

dental medicine integrates the art

1. A mil ennium of dentistry—A look into the

and necessary to make a choice.

and science of dentistry, personal

past, present and future of dentistry. Available

Trust is considered an integral

values and beliefs, and a profes-

part of the dentist-patient relation-

sional code of ethics into a decision-

Accessed July 20, 2007.

ship and is essential for informed

making framework for providing

2. Healthy People 2010, vol. 2. Washington, DC:

Department of Health and Human Services;

appropriate care.

Even as technology advances

3. American Dental Association. Principles of eth-

rapidly and aggressive marketing

ics and code of professional conduct. Available

practices appear to be increasingly

The authors wish to thank the team

ada_code.pdf. Accessed June 2007.

necessary, clinicians cannot be con-

of technicians at BecDen Dental

4. Windholrn R, Cuenin M. An implant versus a

sidered incompetent simply because

Laboratory (Draper, Utah) for their

conventional fixed prosthesis: A case report.

Gen Dent 2007;55:44-47.

they make decisions that other cli-

artistic talents demonstrated in each

5. Sadowsky D. The moral dilemmas of the multi-

nicians may view as inappropriate,

case and the staff in the Department

ple prescription in dentistry. J Am Coll Dent

provided there is sound scientific

of Nursing at the University of

6. Ethics handbook for dentists. Gaithersburg,

rationale behind the choice of treat-

Akron for their assistance.

MD: American College of Dentists;2004.

ment rendered in good faith. Pro-

7. Weinstein B. Dental ethics. Philadelphia: Lea

viding treatment without informed

& Febiger;1993.

8. Huff KD, Leffler WG, Campbell D. Ethics are

consent devalues patient autonomy.

The authors have received no

moral, but morality is not ethics. Gen Dent

Because dentistry is an ethical

financial reward from any of the

profession, the ethical obligations

products, companies, or laboratories

9. Kelley J. Ethical dentistry: A time proven solu-

tion to a modern problem. J Am Coll Dent

of the dentist must guide every

mentioned in this article.

treatment decision. If neither the

10. Nichols P, Winslow G. What patients need ver-

patient nor the dentist are comfort-

sus what they want. Gen Dent 2003;51:503-

able with the decision, there is no

Dr. Kevin Huff is a clinical instruc-

11. Perel M. Endodontics or implants: Is it that

obligation for the dentist to treat

tor, Department of Comprehensive

simple? Implant Dent 2006;15:111.

the patient beyond stabilizing a life-

Care, Case School of Dental Medi-

Published with permission by the Academy of General

threatening urgent condition. A

cine in Cleveland, Ohio, where Dr.

Dentistry. Copyright 2008 by the Academy of

dentist should not perform a treat-

Farah is an associate clinical profes-

General Dentistry. All rights reserved.

ment that would violate another

sor. Dr. Marlene Huff is an associate

ethical principle simply to support

professor, Col ege of Nursing,

patient autonomy. Ethical utiliza-

University of Akron in Akron, OH.

www.agd.org General Dentistry September/October 2008 547

Source: http://www.doctorhuff.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/EthicalDecisionMakingforMultiplePrescriptionDentistry.pdf

UNIVERSITAS SCIENTIARUM Enero-junio de 2005 Revista de la Facultad de CienciasPONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD JAVERIANA Vol. 10, No. 1, 97-108 EFFECTIVENESS OF ELECTROLYZED OXIDIZING WATER Listeria monocytogenes IN LETTUCE Casadiego Laíd Paola1, Cuartas Vivian Rocío1, Mercado Marcela 1, Díaz Milciades2 y Carrascal Ana Karina1 1Laboratorio de Microbiología de Alimentos, Departamento de Microbiología

CATALOGO GENERALEGENERAL CATALOGUE made in Italy, made in F.A.R.G. Nei primi anni Sessanta ad Invorio, nella provincia di Novara, da sempre distretto di eccellenza nella produzione dell'industriadella rubinetteria, Giampiero Conton inizia la sua attività fondando la Rubinetteria Conton. Inizialmente l'azienda ebbe comescopo principale la commercializzazione di materiale idrosanitario; l'intuito del fondatore e alcuni segnali provenienti dallaclientela fecero capire le aperture del mercato e la possibilità di investire con ottimi risultati nella produzione di rubinetti agalleggiante con relative sfere in materiale plastico e in rame, senza dover fare i conti con una concorrenza troppo numerosa.E' nel 1996 che nasce F.A.R.G., naturale evoluzione di Rubinetteria Conton, che opera oggi su un'area di circa 15.000 mq dicui 5.000 mq coperti dedicati ai processi produttivi. Nel tempo la gamma dei prodotti si è ampliata con l'introduzione dialcuni componenti per impianti idrosanitari mantenendo la garanzia di qualità attestata da una produzione interamente ‘Made in Italy'. La costante attenzione della qualità, l'utilizzo di tecnologie avanzate e una rete di vendita che si avvale dellacollaborazione di agenti presenti sul territorio, hanno portato l'azienda a imporsi sul mercato nazionale e su quello estero.